Few Greek legends are more rousing than the slaying of the Minotaur by the Athenian hero Theseus. How he fought and killed the dreaded half-man, half-bull that lurked under the Minoan city of Knossos in a deep, dark labyrinth.

Theseus and the Minotaur are the stuff of sagas dreamed up by the ancient

Greeks but the labyrinth – did it exist, or is it a confection of the imagination

cultivated over the centuries? That’s one of the questions Labyrinth: Knossos, Myth and Reality at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, attempts to answer in

an exhibition that burrows into a story so complicated that the catalogue

supplies a timeline to help understand how the saga came to influence generations of archaeologists, historians and romantics.

And what a timeline. The killing of the Minotaur is one chapter in a chronicle that combines the bloody shenanigans of Game of Thrones with the malice of Succession – a veritable box-set of wayward gods, involving murder, quasi-bestiality, wars and suicide, not to mention an ill-fated attempt to fly.

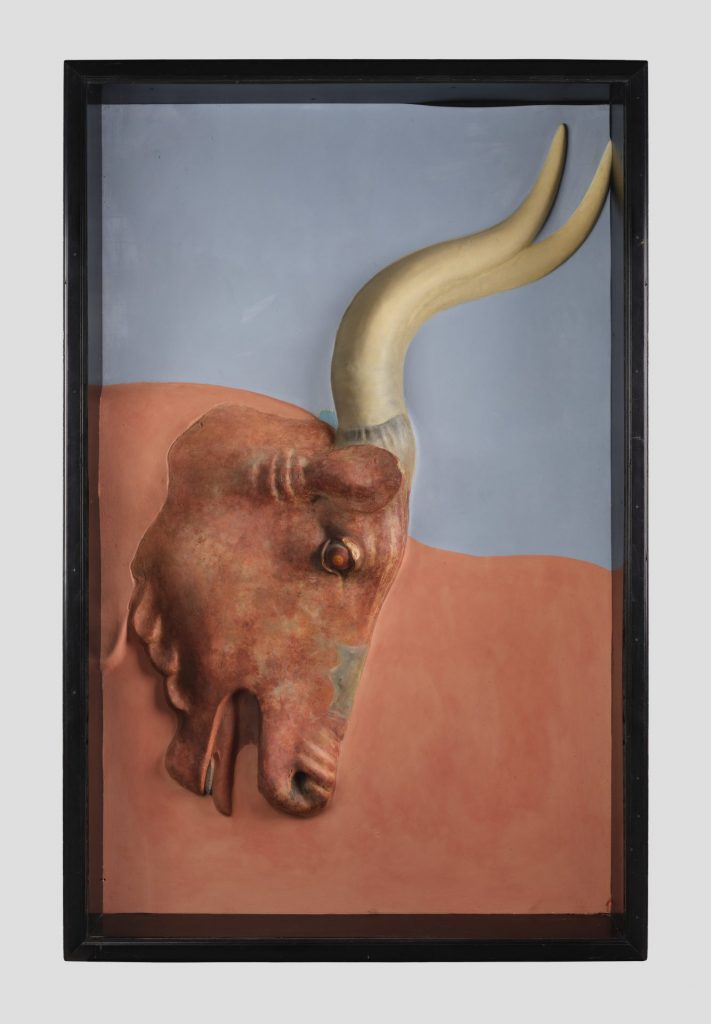

The beast takes centre stage. A bust of the creature greets the visitor at the start of the exhibition: a startling sight, its white marble gleaming against the subdued lighting of the gallery. He looks less menacing than expected, his missing limbs making him look off-balance, perhaps even a little cowed,

but the monster is characterised with all the ugly force of the popular imagination by Pablo Picasso’s La Minotauromachie (1935) on one side and

the sculptor Michael Ayrton’s Minotaur Risen (1971) to the other.

In Greek legend, the beast is the progeny of Pasiphae, wife of the Minoan king Minos, who falls in love with a white bull and commissions Daedalus, mythical Greek inventor, to build an artificial cow for her to hide inside and consummate the affair. Minos asks Daedalus to build tunnels that are so confusing that the Minotaur could never escape – but ensures it survives by ordering that 14 young men and women from Athens should be sacrificed to it at regular intervals.

Theseus volunteers to be one of the victims but Ariadne, the daughter of Minos who has fallen in love with him, gives him a ball of thread and he is able to despatch the beast and retrace his steps out of the labyrinth.

But what are the facts? The myths are readily identified – but the reality? Was

there a labyrinth? What do we know about Knossos and the Minoan civilisation that flourished from about 3000BC to 1100BC and bears the name

of its legendary ruler?

The answers – some at least – can be found in more than 200 objects, including ceramics and frescoes, coins and maps. Take just one, modestly

displayed opposite the marble Minotaur that greets the visitor. It is a fragment, only 21.5 by 20cm, of painted plaster from 1700-1600BC found in the palace of Knossos. Marked with geometric lines, it certainly looks like a simple representation of a maze or labyrinth.

The scrap was found in 1894 and must have been seen by the archaeologist

Arthur Evans, who first visited Crete that year and won the right to excavate

the rocky hillside on which Knossos had been built. Evans, who worked as

Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum for 25 years from 1884 and transformed the institution into an internationally important archaeological centre, spent from 1900 to 1905 digging, researching, and opening the eyes of the world to the glories of Minoan culture. He donated a vast collection of material he had excavated in Crete to the museum, including clay, stone and metal vessels, fresco fragments, bronze weapons and tools, jewellery and figurines.

He was not the first to discover Knossos: that had been the work of the Cretan businessman and scholar Minos Kalokairinos in 1878, but the Greek was generous in sharing the knowledge he had accrued. Evans, who was later to buy land around the site, uncovered building after building within the palace, more than 1,000 rooms lined with colonnades and linked by flights of stairs, stores for wheat, oil and treasure as well as workshops and a sophisticated system of drains and pipes that supplied the palace with water and sanitation.

Inevitably, Evans was impressed by the sheer size and complexity of the place and on March 21 1894 he wrote: “I see no reason for not thinking that

the mysterious complication of passages is the labyrinth,” and his own detailed sketches and plans of the site, even down to the palace’s drainage

system, help to explain how the “reality” of the labyrinth took a grip.

He was not the first to be attracted by the legend. Generations of archaeologists before him had tried to uncover the secret of the labyrinth, but his optimism was encouraged by the finds he had made – and the evidence he found. Evans may well have seen maps, or at least been aware of them, by the likes of the Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius – publisher of the world’s first atlas, which clearly marks a site on Crete as Labyrinthus.

Fragments of papyrus discovered in Egypt at the turn of the 20th century had a scrap from a play about Theseus by the Greek tragedian Euripides, who was born in about 480BC, in which he states: “Theseus arrived in Crete and killed the Minotaur and easily found his way out with the help of Daedalus.” (In the familiar coda to the saga, Daedalus tried to escape Crete with his son Icarus by flying to safety, but Icarus went too close to the sun and plummeted to his doom).

Evans would have been further encouraged by the discovery of a tiny silver coin from around 300-270BC that has Hera, goddess of marriage and women on one side, and on the other straight, intersecting lines that, again, look like a labyrinth. He must have been influenced by vases dating back to about 500BC that depict in graphic detail how Theseus clubbed or stabbed the beast to death.

Evans also uncovered a labrys, a double-headed axe, which he argued was the symbol of a Minoan cult dedicated to Zeus, whose traditional birthplace was Crete, but also the origin of the word labyrinth – an etymology disputed by most scholars. He wrote: “We must in fact recognise in this vast building – with its maze of corridors and chambers and its network of subterranean ducts – the local habitation and home of the traditional Labyrinth.”

But how much of his conclusion was based on fact and how much on a

romantic yearning? Antonis Kotsonas, a classical archaeologist at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York University, argued that the legendary maze was just that – a fantastical fiction from Roman times, elaborated over the centuries and further enhanced when Greece,

emerging from the collapse of the Ottoman empire and seeking a sense of

national identity, seized on Theseus and his deeds as a heroic symbol. Kotsonas suggested that the labyrinth was cast as “real”, completing its

“metamorphosis from the abstract memory to a physical monument”.

However, there may be a more realistic contender for the site of the labyrinth. Caves carved out of limestone around 30 miles from Knossos, near the Roman city of Gortyn, appear to be partially man-made and are accessible only through a very narrow crevice that opens up into a series of interlocking tunnels.

The first recorded author to make this connection was a sixth-century Byzantine scholar, who wrote: “The Minotaur left for the area of the Labyrinth. He went up to a mountain and hid inside a cave. Theseus chased

him and learnt from someone where he was hiding; he pulled him out and

killed him directly. And he entered Gortyn and celebrated his triumph.”

Several Victorian archaeologists pursued this theory, including one Robert Pashley in 1834 who, after exploring the caves of Gortyn, declared: “The forms of the mythical labyrinth, as exhibited on the coins of Cnossos (sic), are naturally varied, since they represent not a material edifice, but a work of the imagination.”

He was scathing about Knossos, writing that it had “dwindled down into this miserable hamlet, and the few shapeless heaps of masonry, which alone recal [sic] to the remembrance of the passing traveller its ancient and bygone splendour”.

Bygone maybe, but Knossos and Crete had enjoyed centuries of Minoan glory, as this exhibition demonstrates with artefacts in bronze and glazed pottery, engraved seals and gold jewellery, which were more elaborate and

luxurious than anything else found in Europe from that era, the Bronze Age.

The artistic flair of Minoan artisans can be appreciated in three cups loaned from the Heraklion Museum in Crete, which were found in the 1890s in the Kamares Cave, an important Minoan shrine. Known as Kamares Ware, they were made as early as 2100BC and decorated with elegant floral and spiral motifs, swirls and lines in white with touches of red that contrast with the dark of the cups.

Evans considered the cups to be the finest examples of Minoan pottery, and

they are considerably more alluring to the untutored eye than the many coins, tablets and small pots he discovered and was allowed to bring back to Oxford.

He was given a small, delicately worked fresco of an olive tree in thanks for his work by the Cretan government, but the original, restored frescoes have

stayed behind in Crete. Instead, watercolour versions adorn the walls of the Ashmolean, made by the same people who pieced together the frescoes and, in the case of the beguiling Ladies in Blue, added faces that had been destroyed long before. It shows a row of elegant women dressed in intricate embroidered jackets dyed in pastel yellows and blues with bejewelled hair and show-off ringlets.

The fresco is a reminder that textiles were probably the most important export of Knossos and that these women, as elegantly turned out as anyone at Ascot’s Ladies Day, were perhaps as powerful as men. The theory is supported by the Grandstand Fresco, which shows a crowd of spectators around the central court. Like the Ladies in Blue, the women are white-skinned, which suggests a more genteel, less onerous lifestyle, while the

men are coloured in red, perhaps because they are working outdoors, doing menial jobs. Furthermore, the women are more carefully drawn than the men, which suggests they were worthy of greater respect.

Evans, however, tended to relegate women to merely religious figures such as priestesses, and as proof of their inferiority he declared that the royal throne was too narrow for women’s hips and would have been suitable only for a slim-hipped king.

One of the most complete restorations is captured in another watercolour, the Taureador Fresco, which depicts two figures looking on while a red-skinned athlete leaps over a bull’s back as it rushes forward in attack. The scene was described memorably by the writer Mary Renault in The King Must Die (1958) as seeming “not to leap, but to hang above the bull, like a dragonfly over the reeds”.

Some suggest that this is nothing to do with a labyrinth, let alone a Minotaur, but instead it was an event something akin to a wild west rodeo in which Minoan “cowboys” showed off their athletic prowess and, as they performed, became burnt red by the sun.

Like so much in this rewarding exhibition, the truth is evanescent. But the imagery is often powerful, such as the lowering bull’s head, a replica of a rhyton, a type of drinking container used in ancient Greece. It has the menace lacked by the marble Minotaur that opens the gallery; maybe because it is in harsh black stone, with white shells for its muzzle and rock crystal and jasper for its baleful red eyes. Evans spotted traces of gold during excavation and decided the missing horns should be made of wood and covered in plaster and gold.

Wherever you look, reality and myth bump into each other. There are facts and there is imagination and there is downright fantasy. Work goes on to dig

out the truth, as the last room in the exhibition, devoted to recent endeavours, demonstrates, with pots, clay figurines, jugs and coins, all of which will appeal to the more academically minded. For those who prefer a dash of Bronze Age bling – a dazzling gold ring from the first century BC, a graceful bird-shaped cosmetic perfume vessel, a bronze dagger with an inlaid griffin. Evidence of an illustrious civilisation.

But as for the labyrinth, without a thread of truth connecting myth to reality, it remains just that; a myth.

Labyrinth: Knossos, Myth and Reality at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, until July 30

Richard Holledge writes about the visual arts for the Wall Street Journal, Gulf

News, FT and New European