As the people of La Palma contemplate the destructive aftermath of the recent three-month volcanic eruption, they may reflect that things could have been a whole lot worse.

The Cumbre Vieja eruption covered more than 1,000 hectares of the Canarian island in lava, destroyed more than 1,000 homes and added 40 hectares of new land as it poured into the sea.

But on the northernmost Canary Island of Lanzarote, nearly 300 years ago, the Timanfaya volcano began a terrifying series of eruptions that would last the best part of six years and cover a third of the best farmland in thick lava.

On the once-fertile high plain of La Geria, the impermeable lava was two metres deep and, in time, it also became covered in tiny fragments of black windblown volcanic dust, or picón. Those islanders who had not fled knew that beneath the new rock was fertile alluvial clay soil. If they could dig through the lava, might it be possible once again to grow something on what had once been fields of potatoes and cereals? Perhaps vines, with their deep, searching roots?

So the farmers hewed deep pits in the lava, called chabocos, using hand tools and, later, dynamite. They used the lava lumps they excavated to build rough, shallow walls to protect the newly planted vines from the rasping north winds that can blow across the rolling plateau.

The legacy of a type of viticulture found nowhere else on earth is mile upon mile of jet black volcanic desert, punctuated by regularly spaced horseshoes of rough walls of lava. As the vines come into leaf in spring, each horseshoe brings a vivid splash of green to the barren acres.

One such vineyard is the family-run El Grifo, founded in 1775, not much more than 30 years after the eruption and claiming to be the oldest on the island. Today it is owned and run by brothers Fermín and Juan José, the fifth generation of the Otamendi family, who acquired the vineyard in the 19th century. Standing in a pit in the lava, in the shade of a 240-year-old vine, Luca Torelli, a manager at El Grifo, describes how good fortune came to smile upon the farmers who strove to bring their devastated land back into production.

It turned out that not only did the walls protect the vines from the wind, but condensation from the Atlantic winds would settle overnight and seep down into the picón, where it was retained and slowly found its way down to the roots of the vines.

“We have a sub-tropical climate and it only rains on 20 days a year,” says Torelli, a former sommelier from Piedmont, Italy. “But the wind off the Atlantic brings humidity and better acidity to the grapes. This combination of hot weather and high acidity is why our white wine is so special.”

The main grape varieties grown on El Grifo’s 65 hectares include Malvasía Volcánica, and Moscatel, from Crete. The fruit is small and yields are only about a tenth of what would be expected in mainland Spain. But the exceptionally dry climate, says Torelli, has kept the island vines free of the phylloxera pest, meaning the old varieties can be grown at ground level without grafting or other intervention. Some vineyards, including El Grifo, have experimented with parallel shelter walls to edge yields up, but harvest remains by hand and takes place in July: earlier than anywhere else in the northern hemisphere.

Lanzarote is lower than other Canary Islands and much nearer to the Sahara, so is much more arid: the vineyards apart, you may see the odd field of prickly pear or aloe vera on La Geria. Further north and east, small fertile areas that escaped the eruptions still support food crops but – with many agricultural workers seeking better wages in tourism – it’s a shrinking sector, leaving viticulture a greater contributor to the economy.

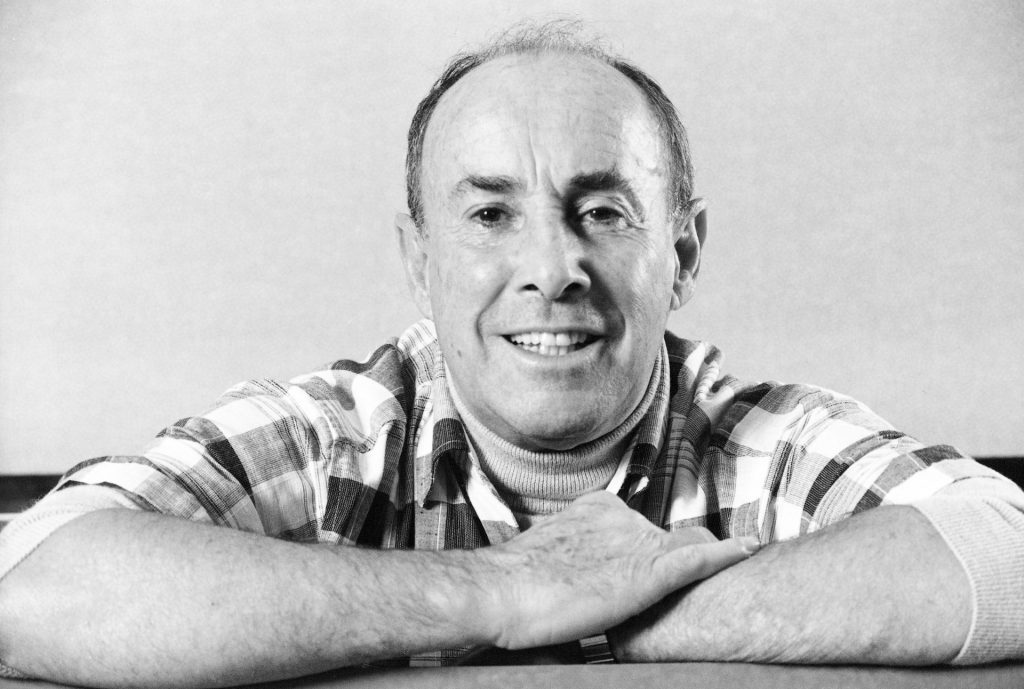

If the farmers wielded the palette knife that produced the green-specked black canvas of the wine-growing landscape, it was the celebrated artist César Manrique who applied the subtle brush strokes that completed the picture that is the distinctive landscape of La Geria today.

Alarmed by what he saw as the desecration of Spain’s Mediterranean coastline in the name of mass tourism, Manrique – who, by the 1980s, was an internationally acclaimed icon of the surrealist movement – conceived for his island a blueprint for a new kind of visitor economy, whose attractions would grow organically from the landscape itself.

With the aid of Pepin Ramirez, a family friend who had become president of the island’s council, he drew up a set of guidelines for future development, including a ban on electricity pylons, advertising hoardings and high-rise buildings.

Only a couple of high-rise developments snuck in before they were banned: a hideous block on the seafront at Puerto del Carmen and the 17-storey Gran Hotel in the capital, Arrecife, which still dominates the city skyline as an iconic reminder of the day the island changed tack.

He devised a series of tourist attractions, specifically evolved out of the lava landscape and characterised by brilliant white flowing shapes, cast in concrete and subtly wrapped around the chaotic volcanic debris. The whites would be highlighted by subterranean ponds of turquoise water and giant cacti.

For La Geria, the changes ushered in by the new rules were subtle: all new houses were now expected to be simple, low and whitewashed, with woodwork picked out in brown or green. Nearer the coast, the “official” colour for doors and windows was blue. Suddenly tumbledown fincas in the wine fields found themselves invested with new value, as the island signed up, seemingly as one, to the Manrique concept. With his iconic miradors (viewpoints), cactus garden, volcano-fired restaurant, underground concert hall and other enduring creations, he became a pioneer of the concept of eco-tourism long before the term gathered traction.

Towards the eastern end of La Geria, he created a monumental modernist sculpture, the Monumento al Campesino, in celebration of those who still cultivated the arid lands.

The artist was also a friend of the Otamendis at El Grifo and, on being told of plans to demolish a large old cellar building to make way for modern new facilities, he persuaded the owners to retain these as a museum dedicated to the evolution of the island’s viticulture. “He told them ‘You are crazy!’,” says Torelli, as he shows me pictures of the artist with the family, and a framed version of the new logo he designed for them. It comprises a deep red sun above the smoking crater of Timanfaya, in the shape of a traditional hat, framed by two palm trees above a stripe of black lava, dotted with vines in the traditional horseshoes.

“Until the middle of the 1980s there were only three or four families still cultivating grapes,” says Torelli. Then Manrique began taking wines to his overseas exhibitions. It was modest, but the first time Lanzarote wine had been exported for 300 years. La Geria is today home to more than 20 modest boutique vineyards, or bodegas, with EU protected Designation of Origin status, conjuring quality wines from low-yield, low-intensity production methods.

For a modest-sized vineyard, El Grifo boasts a surprising variety of wines. Torelli guides me through some of them, saving till last the champagne-method Brut and the Malvasía Canari dessert wine. At close to €100 (£83) for a 50cl bottle, the latter is truly one for the cognoscenti and seeks to replicate the 17th-century wines that found their way to Canary Wharf in London. It combines Malvasía vintages from 1956, 1970 and 1997 with wine from sun-dried late-season grapes.

By virtue of their limited production, Lanzarote wines will remain a product for the discerning visitor or a niche export, but Torelli aims to share them with an ever wider audience, he says, as he guides me through a Manrique-style conversion that will become a school for aspiring sommeliers. Manrique died tragically in a road accident in 1992: his legacy endures not just through Lanzarote’s built heritage, but also through the most celebrated product of its endless black highlands.