Jock McFadyen’s studio is sandwiched between the corrugated iron doors of lock-up garages, opposite Chu’s garage – crash repairs a speciality – and overlooks a railway viaduct along which trains squeal and rumble. Duck down a grubby alley and there you are.

But disconcertingly we appear to be in a motorbike repair shop with bits of engine and the tools of the mechanic’s trade spread out in oily disarray.

McFadyen is motorbike mad. He’s got a dozen or so of them in all, but pride of place is taken by the very Honda he bought 56 years ago and rode from Scotland to London in 1969 to see the Rolling Stones in the legendary Hyde Park concert. He sold the bike but spotted it on a specialist site many years later and bought it back. The magazine Classic Bike headlined the story: Sympathy for the dishevelled.

The bike was the same model as the one celebrated in the book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, which achieved cult status (and sales) in the 1970s with its proselytising for “a state of calm attentiveness in which one’s actions are guided by intuition rather than by conscious effort.”

It’s not too much of a stretch to suggest there is something of the “calm attentiveness” about McFadyen. His approach to a series of paintings about the Berlin Wall in 1991 was described by the late art critic Tom Lubbock as “like a sightseer without a guidebook”, an appraisal McFadyen cheerfully accepts: “It struck a chord as he had perfectly described my attitude to painting places, and since that time I have carried the words close to my heart as I wander about not looking for anything.”

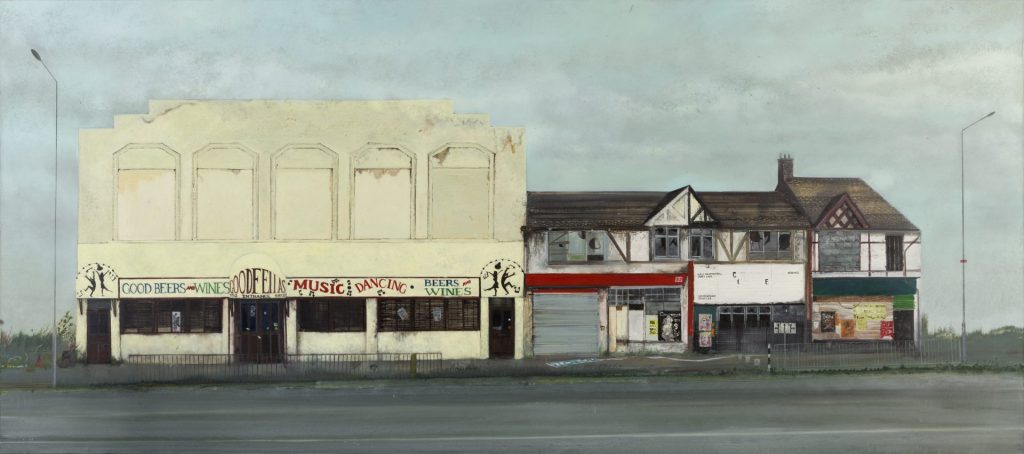

Hence the title of his retrospective at the Royal Academy, Tourist without a Guidebook, planned to celebrate his 70th birthday last year. It features a selection of the paintings of the East End of London made over the past 30 years that have established him as the “laureate of stagnant canals, filling stations and late-night football pitches”, as the writer and friend Iain Sinclair dubbed him.

This is a world of run-down and abandoned buildings straggling along the A31 as it wends from the City to Southend, contrasting with the shiny citadels of Canary Wharf in the background. Here we find boarded-up shopfronts and broken windows, empty streets and lonely places, such as Goodfellas nightclub – once a magnet for Essex youth, but shabby and depressing when McFadyen painted it and now closed. His scenes of deserted underground stations are gloomy and menacing, enlivened only by splashes of colour. If people appear, they are on the margins, incidental to the subject.

If the workshop is a clutter of mechanical paraphernalia, upstairs more than matches it for apparent chaos. As one might expect, it is a gallimaufry of brushes, squeezed paint tubes, half-empty pots and paintings stacked away or propped against the walls. It would have made a worthy contender for the Whitechapel Gallery’s new exhibition, A Century of the Artist’s Studio.

He drags out a painting and turns it upright. Called Roman Road 1941, it was taken from a photograph after a German bombing raid. It shows a damaged skyline of once-fine Georgian houses, which have today been almost entirely replaced by a 1970s block of flats and a fire station, where The Falcon pub used to stand. His own house to the left of the wreckage is one of only two standing after the Blitz, though the front of the house was blown off.

Crows, those avian scavengers, float in a bright sky, reminders that the area is haunted by death. Nearby London Fields was a plague burial ground in the 17th century and 172 people died in a stampede trying to shelter from air raids in Bethnal Green underground station during the war.

“London is a kind of a swamp,” says McFadyen who, despite having lived in the city for 50 years, still has his Paisley accent. “There are layers and layers and layers of historical fact which are physical and come and go like those sped-up cinematic frames of trees growing fast and clouds racing by. It’s a never-ending building site.”

Much of his early work was figurative, but when he was commissioned by the Imperial War Museum in 1991 to paint the newly tumbled Berlin Wall he found he was concentrating more on the inspiration he got from the wall itself than on the people around it. At about the same time, he designed the ballet set for The Judas Tree, Kenneth MacMillan’s last ballet for the Royal Opera House, and realised that he did not need to portray figures when there were already people on stage. Places became his focus.

But that brings its own problems. Now, he argues, if you are a figurative artist people write about the reason for the painting; who is the person? What are they doing? Is it a portrait? Is it a story?

“With figurative painting you suffer from these deductions in a way that abstract artists do not. Jasper Johns, Howard Hodgkin, Sean Scully – you don’t question – you think, that’s a painting, that’s what it is.

“In music it’s like a guitar solo. You have to listen to it to see if it evokes feelings, but if you’re figurative you are lumbered with that misinterpretation. You’ve opened your door for literary analysis.

“In fact, it is a bit like writing in the way that the reader is not being told stuff, not being led, until the penny drops. I step right back and have the painting tell you where we are going.”

He pulls out another work from the racks, the hard lines of a club bar with garish decorations and, on the periphery, a girl dolled up for a night on the town.

He explains that he reworked some of his figurative paintings from the 1980s during lockdown with scenes in clubs and pubs featuring glum refugees of the night such as the solitary girl and the two strap-hanging, out-on-the-town party girls in Nightbus.

“I had no intention of doing that,” admits McFadyen. “Doing these paintings is like having a divining stick and discovering that there is water here, so having painted a version for one reason, 20 years later I found myself doing the nightclub paintings. The door is ajar between the unconscious and the conscious mind – the conscious mind thinks it’s doing one thing but actually, you are being pushed in another by the process of painting.”

Compared with the garish scenes in the nightclub, many of his paintings appear, at first glance, to be in a different style, less complex perhaps, almost abstract, with sparse landscapes, or seashores, endless skies, a lonely dog. Not so, he says, and holds up a work in dark blues and indigos with just a few flecks of colour on the horizon to signal signs of life.

“I’m surprised you think they are different. I would certainly expect another painter to know they were all by me because of the touch. It’s all about the paint. That’s what makes the work distinctive – like handwriting or someone’s voice.

“It’s what a lot of painters call wet upon wet, more like a watercolour. You don’t do a bit and come back the next day, start a bit and leave it, you put everything down and keep the paint moving all the time the way watercolours would do to get depth. This feeling of drips is like being in a train rushing past.”

He actually sent one of his paintings to an artist friend with a hoax signature on it. He recognised whose work it was immediately.

“If you read a novel you can have sex, a killing, a lorry driver, a car, a scene sitting in a café, visiting the death bed of your mother, you can chuck it all in, but with painters we are involved with something which is half-way between fiction and furniture. There are lots of different questions being asked of the viewer.”

For a man who had his heyday in the 1980s (his words) and fell off a financial cliff in the 1990s “like a cartoon character who keeps running until he realises there is nothing underneath”, it should go without saying that he wants to sell as many and as often as possible.

But perversely, he says, he is beginning to prefer having them in the studio.

“When you are a very successful artist your dealer sends people round and says, OK, we’ve got Frieze coming up, so we’ll have this one and this one and some of those. Some artists have workshops with 10 people who produce product – as they have done from the Renaissance and before – but artists like me, like LS Lowry, one of my heroes, I have never done that, I work alone, I don’t want to be told what to do.”

He cites the example of Expressionist superstar JM Basquiat, who was reputed to paint while on flights, to meet the insatiable demand for his works.

“And look what happened; he burned out. The way I work, it takes a long time for my paintings to emerge from the ether. I might just do the last bit, the last five minutes, the last little green blob, two years later, or even 20 years later.”

He reaches for another aphorism from Zen and the Art of Painting a Picture.

“It’s like gardening: you go into it, do a bit of pruning, pot something, plant something. You don’t go and make a garden, that’s not what it’s like.”

Jock McFadyen, Tourist without a Guidebook, at the Royal Academy, London, until April 10.