Today, Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) is remembered as much for his voluptuous women as for the broader successes of a glittering and exceptionally productive career, which yielded some 1,400 paintings, among them monumental mythological and historical cycles, altarpieces and portraiture.

“Rubenesque” remains secure in common usage, and evokes the painter’s trademark generously proportioned, rosy-skinned nudes as vividly as it did a century or so ago, when Vita Sackville-West described her lover, Rosamund Grosvenor, as the “Rubens lady”.

Descriptive as it is, like all labels it tends towards oversimplification, and wrongly implies that Rubens painted only one type of woman. This misconception is challenged by a new exhibition opening at Dulwich Picture Gallery later this month.

Rubens & Women looks beyond the eroticised nudes for which Rubens is best known to find the real women who influenced his life and work, traces of whom are found throughout his vast oeuvre. Based around the gallery’s own considerable collection of works by Rubens, the exhibition brings together around 40 paintings and drawings, including loans from the Uffizi, Florence and the Snijders&Rockox House, Antwerp.

He was one of the most celebrated painters, and undoubtedly the most prolific, of the 17th century, but in his self-portraits Rubens chose to identify himself not as an artist with his brushes, but as a gentleman, distinguished as such by a sword at his hand, or by a flamboyant hat. As a polymath who spoke six languages, at ease in the courts of Europe’s rulers, Rubens excelled in his parallel career as a diplomat, and in the bloody tumult of the almost total war that ravaged Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, he acted as an envoy on behalf of the court of the Spanish Netherlands, where he served Archduchess Isabel Clara Eugenia, the daughter of Philip II of Spain, as both painter and emissary from 1609 until her death in 1633.

Self-discipline and good health were the key to his prodigious workrate, and according to the French painter and theorist Roger de Piles, writing in 1681, he not only got up at 4am, but “ate little at dinner, so that the vapour of what he ate should not prevent him from applying himself, and so that labour should not impede digestion”.

As a court painter, Rubens was exempt from guild regulations that limited numbers of pupils and assistants, and consequently, the critic and historian James Hall describes his operation as “a painting factory, turning out works in all genres and sizes”. Among his staff were specialist painters, tasked with details of landscapes or draperies, and his assistants were often highly skilled, as in the case of Van Dyck, Rubens’s most famous assistant. Even so, a painting made entirely by Rubens himself cost double that of a workshop painting.

His multi-tasking was legendary, as reported by Otto Sperling, later physician at the court of Denmark, who visited “the famous and eminent painter Rubens” at home in Antwerp in April 1621:

“The master was working on a canvas while listening to a reading of Tacitus and simultaneously dictating a letter. Since we did not dare interrupt him, he himself addressed us, while continuing to paint, listen to the reading and dictate his letter, as if to give proof of his great ingenuity.”

The demands of Rubens’s international, multi-faceted career did not limit his personal life, and he attended Mass twice a day, rode every afternoon and dined with friends each evening, all the while nurturing a cherished family life. After the death of his first wife, Isabella Brant, he married Helena Fourment in 1630, and both women are immortalised not just in portraits, but in Rubens’s religious and allegorical paintings. According to Jennifer Scott, director of the Dulwich Picture Gallery, Rubens’s love for his second wife is evident in his paintings: “Every face he painted following their marriage in 1630 through to his death in 1640 bears her resemblance.”

Two of his most beautiful and tender portraits are of his eldest daughter, Clara Serena, at age five, and then again at age 12, shortly before her death just prior to her 13th birthday. Experts now agree that this moving and intimate painting is indeed by Rubens, and for the next three years at least it is on long-term loan to the gallery.

Naturally enough, Rubens’s earliest female role model was his mother, Maria Pypelinckx, by all accounts a courageous and resourceful woman who saw her family through an extended period of hardship that arose, at least in part, from the religious and political conflicts that dogged Europe from the 16th century onwards. The trauma of the protestant Reformation and the Counter-Reformation that followed, and multiple other factors, notably the relentless expansionism of the Habsburg empire, combined to fuel a long and brutal state of war in Europe.

Maria, a Catholic, was the daughter of wealthy Antwerp merchants, and married the lawyer Jan Rubens in 1561. His Calvinist leanings brought him under suspicion in Catholic Antwerp, and the couple fled the city with their young family, settling in Cologne in 1568. Here, Jan acted as legal adviser to the German princess Anna of Saxony, who in 1561 had married William of Orange, now remembered as the founder of the Netherlands. Jan and Anna had an affair, resulting in the birth of a child, and in 1571, Rubens’s father was arrested and imprisoned.

Maria remained loyal to her husband, writing, “I would gladly help you out of there with my own blood, if that were possible.” She petitioned the authorities and secured his partial release in 1573, when the family was reunited, resulting in three more children, the third dying at birth. Eventually, the family was allowed to return to Cologne, from where Maria is recorded as operating as a merchant running her own business.

Following the death of Jan Rubens in 1587, and after more than 20 years in exile, Maria returned to Antwerp, then still one of northern Europe’s principal trading centres. She was accompanied by three of her four surviving children, among them Peter Paul Rubens; the eldest, Jan-Baptist, had travelled to Italy to pursue a career as a painter.

Maria went to great lengths to keep secret the events that had led to the family’s exile, and worked hard to ensure the future prospects of her children. Rubens’s humanist education supplied the knowledge of classical civilisation and culture so central to his paintings, and during a subsequent period in an aristocratic household he learned the finer points of etiquette and courtly behaviour that would stand him in good stead as a diplomat.

Exactly how he came to be a painter is not clear, but by 1598 he had registered as an independent master, and left for Italy two years later, where he was employed at the court of Duke Vincenzo I Gonzaga in Mantua, returning to Antwerp only when he received news of his mother’s illness in the autumn of 1608.

Until now, Maria has been overlooked as merely the wife and mother of great men. But the Dulwich show emphasises her importance as an exemplar of female courage, resourcefulness and resilience, and curators Ben van Beneden, former director of the Rubenshuis, and independent art historian Amy Orrock suggest that she was the model for the “paragons of female agency, brimming with character and gravitas” that dominate Rubens’s female figures. Specifically, they suggest that Maria may have inspired two paintings on the theme of “dangerously powerful women”, made in the months after her death. Samson and Delilah, c.1609-10, now in the National Gallery, and commissioned by Rubens’s friend Nicolaas Rockox, and Judith Beheading Holofernes, now known only through a print made after the lost painting, could have been intended as tributes to the heroic conduct of Maria Rubens.

The inspiration that Rubens took from both his wives is more easily traced: not only do we have their portraits as reference points, but finished paintings of his children and drawings made from life models indicate the extent to which he relied on observations of real people in his work. Painting from life took on a special importance in the charged atmosphere of the Counter-Reformation, as the resurgent Catholic church sponsored a new wave of image-making characterised by its ability to stir and inspire the faithful. Emotional connection was key, and Rubens clearly drew on the women and children around him to create his tender depictions of the holy family.

It is reasonable to suppose that one of Rubens’s own small children was the inspiration for the sleeping toddler in The Virgin in Adoration before the Christ Child, c.1616-19, and certainly the Virgin is a portrait of his wife, Isabella.

Thanks in large part to the influence of his Spanish patron, Archduchess Isabel Clara Eugenia, Rubens was in demand across Catholic Europe, and likenesses of his wives and children were unlikely to be recognised among his many other sources of inspiration.

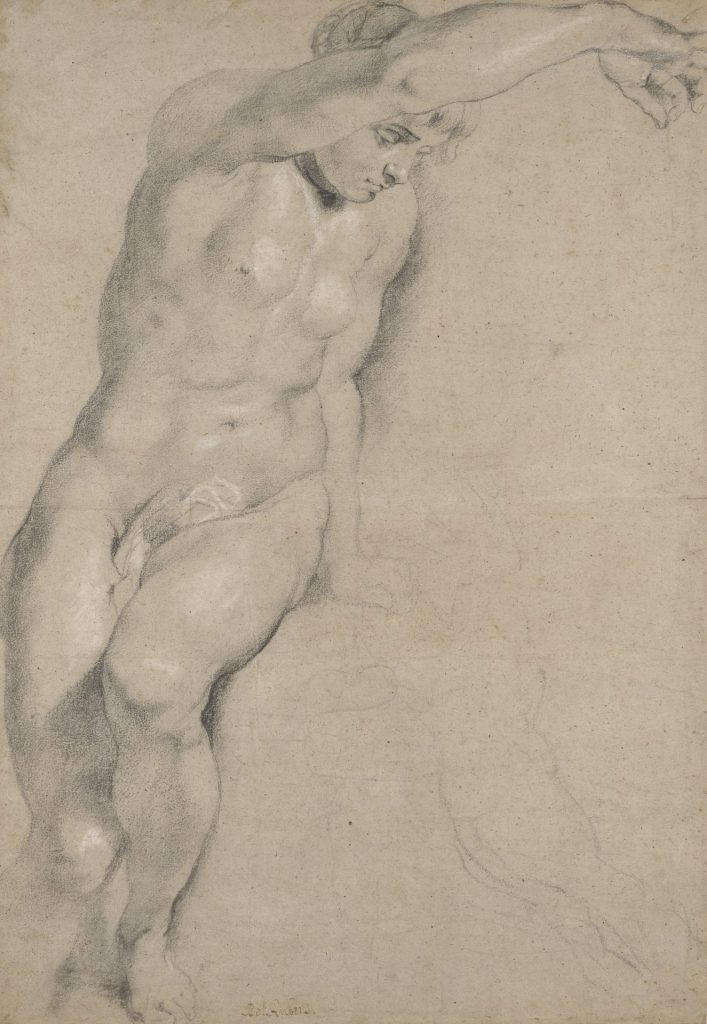

Rubens adopted the Italian practice of drawing from life, and the exhibition includes numerous drawings and oil sketches of models, some of whom would have been members of his extended family. As a man of considerable erudition and accomplishment, Rubens took references from diverse sources, including the works of revered Old Masters including Holbein and Michelangelo, whose strong-bodied and rather masculine female figures influenced his own depictions of heroic women. Classical sculpture was also a source, and the Roman Crouching Venus first seen by Rubens in the court at Mantua recurs as a motif in his work, including in Three Nymphs with a Cornucopia, c.1625-28, on loan from the Prado, Madrid.

Rubens’s second wife was renowned as “the loveliest woman in all of Flanders”, and she often appears as a goddess or nymph in the gorgeous mythological paintings of his later years, when, writes Orrock, his “vision of women was at its most extravagant and sensuous”. In The Birth of The Milky Way, 1636-38, one of 60 mythological paintings commissioned for Philip IV and completed in an astonishing 18 months, the face of Juno, queen of the gods, is Helena’s. Her relative fame meant that she could be recognised, and in one recorded instance the governor of the Netherlands identified Helena in a depiction of a nude Venus.

At times, this sort of fame must have been awkward at the very least, and the history of Het Pelsken (The Little Fur), 1636-38, a full-length nude portrait of Helena unfortunately too fragile to leave Vienna, gives an unusual insight into the sensitivities of treasured but intimate works of art. Rubens left the painting to Helena in his will, and when she remarried she left it to her second husband. Later on, she changed the instruction so that the painting could only be inherited by Rubens’s direct descendants, and though her reasons are not recorded, we can speculate on the special significance of the painting as a memento of her first marriage. The curators note too that although her second marriage lasted considerably longer than her first, it was Rubens she chose to be buried next to.

From our current vantage point, the portraits of nobles and royalty that dominated the early years of Rubens’s career are easily as remote as his religious and mythological heroines. But Rubens’s ability to command our emotions, so brilliantly employed in his religious imagery, is put to excellent service in this exhibition, as the real women behind the paintings step forward.

Rubens & Women, Dulwich Picture Gallery, September 7, 2023 – January 28, 2024