It is fair to say that newspapers haven’t exactly been overflowing with good news lately. Like innocent bystanders stuck in the middle of a shoot-out in a gangster movie, catching up on current affairs often feels like getting attacked from all sides, for no obvious reason.

This is why positive developments, no matter how small, should be both applauded and purposely underlined. Take the story which came out recently, publicised by the Four Day Week Foundation.

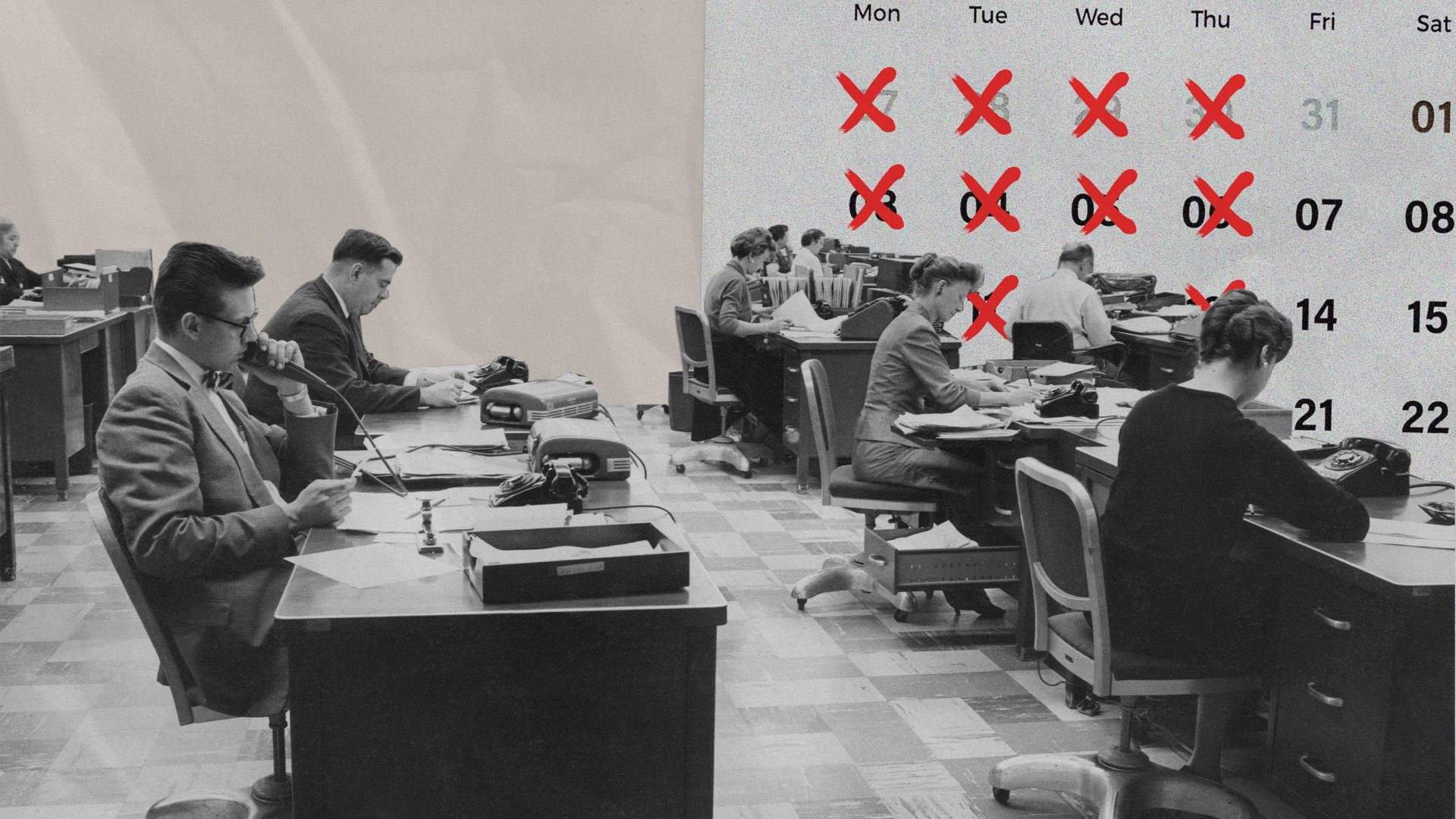

According to them, over 200 British companies have now committed to offering shorter working weeks to their employees, with no loss of pay. The move will affect over 5,000 workers, the majority of whom work in marketing, advertising and technology firms, as well as charities.

This may not feel like much more than a drop in the ocean so far, but it doesn’t mean it shouldn’t make us feel optimistic. The four-day working week campaign has existed in one form or another for a very long time. Back in the 1950s, Winston Churchill himself predicted that, with the right technological advances, people could get “a four-day week, then three days’ fun”. The former prime minister was, quite famously, no woke snowflake.

Seven decades have since passed, and we now live in a world he would find unrecognisable. It surely must be time for things to get shaken up a bit, especially since the five-day week is now more than a century old. Our lives have changed dramatically over the past hundred years, why shouldn’t our working practices evolve as well?

2025 also feels like a good time to start making that case seriously, for a number of reasons. Firstly, the five-year anniversary of the first Covid lockdown will take place in a few weeks. Though it is understandable that people were keen to return to their old lives as quickly as possible after those traumatic months, some lessons should surely be learned from the pandemic. What does it tell us that a significant portion of the population said, years later, that they were happier in lockdown than out of it?

Secondly, the dullness of the Labour government can and should be used as an excuse for people elsewhere to start acting more ambitiously. There is nothing especially ideological or passionate about Keir Starmer, but he is a reasonable man. Show him a way forward that could work, and inspire people, and he may well follow.

It also seems worth remembering that Angela Rayner once backed the four-day week, as did several high profile Labour MPs. They should be able to make the case internally, if enough external pressure is applied.

Finally, times of dire opposition can sometimes lead to the greatest social advancements. Donald Trump is back in the White House, and his white supremacist poodle, Elon Musk, is running amok. Together, they have been trying to bully companies into forcing their workers back into the office five days a week. Already, some American companies are beginning to call time on hybrid working.

The move feels both counterproductive and pointlessly cruel, but should be used as a cautionary tale on this side of the pond. America is going backwards, but that doesn’t mean we should. Instead, shouldn’t Europe try to move forward, be bold and innovative? Shouldn’t Britain?

Changes that affect 5,000 people across 200 companies may not feel like a game-changer quite yet, but that’s fine. Every movement has to begin somewhere. If those workers and companies are found to be thriving in two, five, eight years, it stands to reason that others will want to emulate them. Over time, more and more workers will be able to spend more time with their families, socialising with their friends, and entertaining themselves in whatever way they see fit.

It may seem utopian now but, once upon a time, so did the five-day week. Unions fought to get those, but they just aren’t powerful enough to do it on their own this time around. It’s up to all of us to try and make that case, and fight for the rights we believe we should have. If Elon Musk thinks it’s a bad idea, it must be worth trying, right?