Mark Cousins is sitting in the bar of the Hotel Europe in Sarajevo’s old town. Things are notably quieter than on his first visit.

When the prolific documentarian came to the Bosnian capital in October 1994, it was halfway through the four year-long siege of Sarajevo. Serb nationalist forces had surrounded the city and were subjecting many of its 400,000 citizens to daily shelling and sniper attacks.

During that horrifying time, Cousins made a base at the Obala Art Centar, the last working cinema in war-torn Sarajevo. Along with other cinephiles from the Edinburgh International Film Festival, he spent a chaotic few weeks showing films to local citizens.

A year later, with the city still under siege, the Sarajevo Film Festival was formally launched, and at this year’s event, Cousins was presented with the honorary Heart of Sarajevo Award, previously won by Mike Leigh, Robert De Niro and Wim Wenders.

At the age of 58, Cousins is making an average of two films a year, building up a filmography that takes in 50-plus projects of between 60 seconds and 15 and a half hours in length.

“When I came to this city in 1994, I had already made The Psychology of Neo-Nazism: Another Journey by Train to Auschwitz, a film about the Holocaust, so I had been in Auschwitz. And yet, Sarajevo felt to me like a kind of concentration camp,” says Cousins. “Along with the terror, the aggression and the tragedy, there was a sense of joy and solidarity in making something in defiance of a siege. I think that defiance has stayed with me and has affected my work ever since.”

Cousins started in TV, co-directing and directing a number of documentaries including Dear Mr Gorbachev, broadcast in 1990. He replaced director Alex Cox as host of BBC2’s cult film strand Moviedrome between 1997 and 2000 and also Scene by Scene, in which he interviewed, among others, Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, David Lynch, Jane Russell and Woody Allen.

He was in his mid-40s when in 2009 he made The First Movie. His first full-length documentary, it won the Prix Italia award, and documents a visit he made to the small village of Goptaka in Iraqi Kurdistan, where he gave local children cameras to make their own films and also showed them classic movies such as ET and Albert Lamorisse’s The Red Balloon. Rather than focus on their suffering, or to portray them as helpless victims in need of western pity, the documentary attempts to humanise Goptaka and its people, and to demonstrate that cinema can help children traumatised by war.

Cousins himself is one of those children. He grew up in Belfast and saw his first dead body at the age of seven – that was in 1972, the bloodiest year of the Troubles, when 479 people were murdered in sectarian-related violence in Northern Ireland. Having a Catholic mother and a Protestant father made Cousins stand out from the crowd. But being born into a mixed marriage made him “fear fundamentalism and have a desire to see a binary in everything,” he says. “I definitely was – and still am – quite a nervous person and I think that came from growing up in Belfast. But when you batter meat, it tenderises it, and Belfast was good for me, in an odd kind of way, because it tenderised me.”

He left Belfast almost 40 years ago. “I was sick of it,” he says. “I hated all the conservative convention, and the religion. I was brought up very Catholic, but I ditched all of that as soon as I read James Joyce.”

Cousins addressed the complexity of his home city (the violence, the history, and the humour) in I Am Belfast. The dream-like emotive film, made in 2016, blends documentary with drama, and is narrated by a 10,000-year-old woman who claims to be the city of Belfast itself. “I was beautiful once,” she tells us. “But I wonder if I became ugly, and if so, why I became ugly.”

Cousins came up with that narrative device after visiting Senegal, which in his 15-hour 2011 documentary The Story Of Film: An Odyssey is described as “just as interesting for films in the 1970s as Los Angeles”. In the first episode we see a clip from Louis Lumière’s Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory in Lyon, which dates from 1895. Cinema was then still in its infancy, but it didn’t take long to emerge.

“A lot of bad film-makers think that cinema is like a novel, where [it’s a simple formula] of character, theme, and plot. But cinema is much more physical than that, and great cinema is closer to poetry than prose,” Cousins says.

The Story of Film is more visual polemic than standard documentary. Referencing 1,000 films made on six continents over 12 decades, it makes a conscious effort to redraw the map of cinema’s history from the late 19th to the early 21st century. Cousins continually reminds us that cinema extends far beyond the hills of Hollywood, and that ideas drive film forward, not money.

Sometimes, however, the documentary edges away from critical analysis and towards hero worship. Not all viewers are likely to agree with his claim that Yasujirō Ozu was the greatest director who ever lived, or that Alfred Hitchcock was a more significant image maker than Pablo Picasso.

Many might agree, however, that Citizen Kane changed cinema, which Cousins states in The Eyes of Orson Welles (2018), his documentary on the life of the American actor, producer and director. Cousins spends much of the film analysing Welles’s artwork, which mostly consists of sketches. He also interviews Welles’s daughter, Beatrice. Mostly, though, his documentary feels like a voyeuristic love letter by an obsessive student.

Many of the documentaries Cousins has made about the history of cinema follow a similar formula. He typically describes the images of the film-makers he is discussing in the present tense. This creates the illusion that the audience is watching the images together with Cousins (whose distinctive voice lurks in the background) in real time. “Wherever I go in the world, it’s mostly young people who come up to me, slightly trembling, saying: your films have changed my life,” says Cousins: “It’s because, I think, my films are quite open, vulnerable, but also very passionate.”

They are also extremely personal. The Story of Looking (2021) is perhaps his most intimate film to date. He appears naked several times throughout the documentary. Once in the shower. Another two times lying in open water.

Made during lockdown, the documentary opens with the director lying supine on his bed, intimately addressing his audience. Most of the narrative takes place the day before Cousins is due to have surgery to remove a cataract in his left eye. He is in a contemplative mood, reflecting on a lifetime of gazing at people and objects. He also invites his audience to think about the hundreds of images they encounter every day: in real life, in film, on TV, and online.

In John Berger’s 1972 television series, Ways of Seeing, the audience was encouraged to view art from a postmodernist perspective. Cousins takes a similar approach. He asks us to look at everything from multiple angles. He feels this way about his own identity, which is part Irish, part Scottish, and part British.

In July, Cousins released My Name is Alfred Hitchcock. It’s narrated by the English mimic Alistair McGowan, who does a good job of imitating Britain’s most celebrated Hollywood auteur. The film’s running joke is that Hitchcock is speaking to his beloved audience from beyond the grave. There are occasional voiceovers from Cousins, too, who talks back to Hitchcock with playful mockery. Mostly, though, we get insights into the technical tricks that Hitchcock used to keep his audience in a state of suspense, fear, and paranoia.

His interests go far beyond the techniques and aesthetics of cinema itself, and last year Cousins directed his most political film to date, The March on Rome, released to coincide with the 100th anniversary of Mussolini’s rise. The film contains archival footage from fascist rallies held in Italy during the 1920s and 30s and suggests that fascism did not go to the grave with Il Duce. Italy’s prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, National Rally’s leader, Marine Le Pen, in France, and the UK home secretary, Suella Braverman, “all draw some of their energy and ideas from outright fascists,” says Cousins.

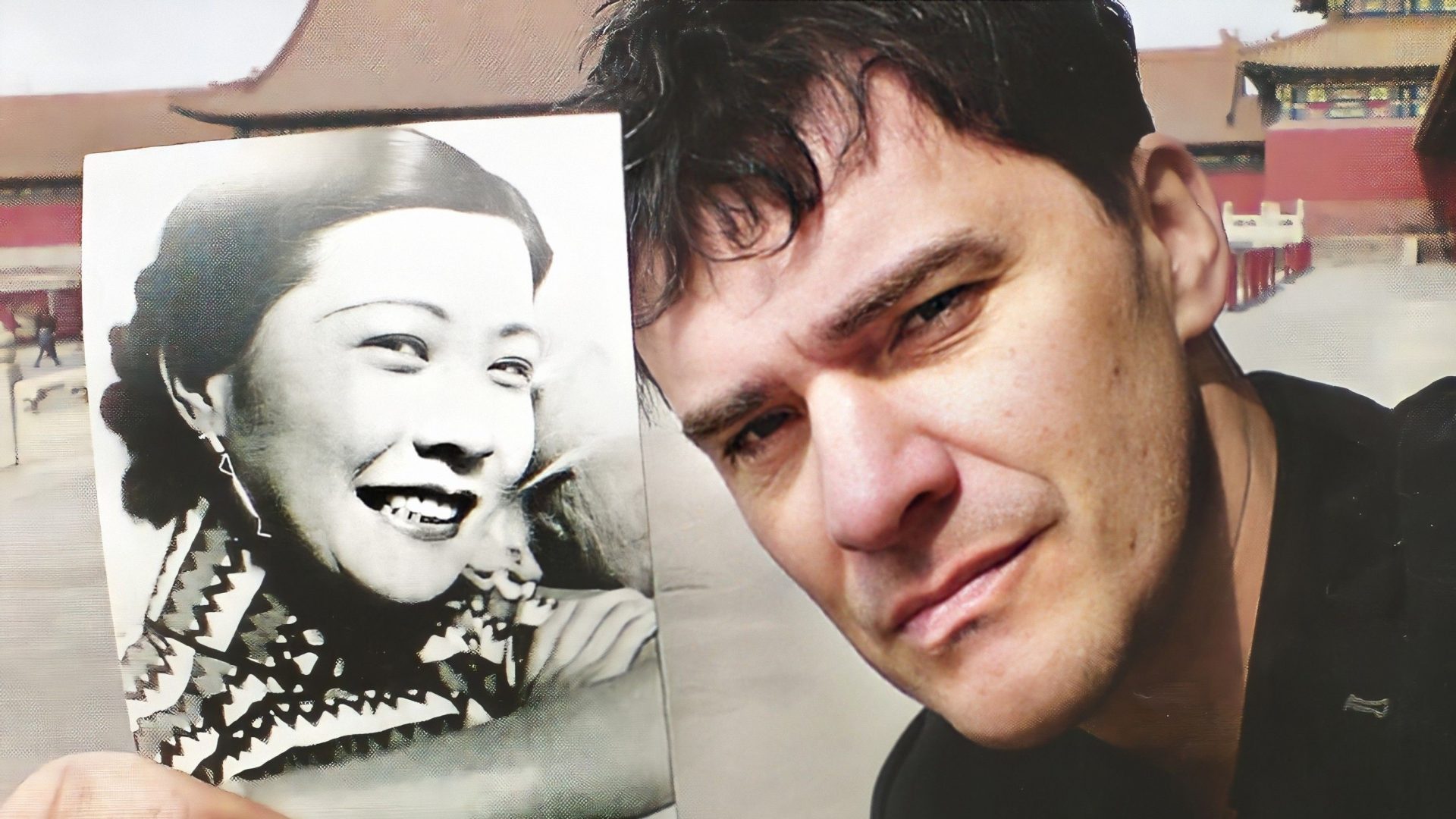

Cousins’ documentaries, made on shoestring budgets, generally tend to get glowing reviews and he has developed a cult following. But his most successful film to date has been Women Make Film (2018). Running for 14 hours, it features the work of 183 female directors. Its phenomenal international success resulted in seven of the female directors featured in the documentary having their films restored by popular demand. Among that list is Kira Muratova. “She is one of the greatest ever film-makers,” says Cousins, proudly pointing to a tattoo he has of the late Ukrainian director on his arm.

His recent documentary on the writer and producer Lynda Myles recently premiered at a festival in the US. A second film, on the painter Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, is now in the works. “She climbed the Alps in one day in 1949 and had such a profound experience that she painted it for the next 50 years,” he says. He is also in the process of completing The Story of Documentary Film, which will run to about 15 or 16 hours. “I’ve already done some shooting for this in Egypt and I’m filming here in Sarajevo too,” he says.

His global reach can present practical problems, especially when working in post-Brexit Britain. “Brexit has created problems for film-makers getting permits for equipment,” he says.

But since Cousins uses very small cameras, he can simply go to various locations, look like a tourist, and not ask for permission to film. “Actually, Brexit has made me have a kind of ‘fuck you’ attitude,” he says.

A workaholic, Cousins tries to film something every day, no matter where he is in the world. “There is the feeling of intoxication, a sense that you cannot stop, but also that you never feel more alive than when you are making something,” he concludes. “But there is also a sense – something I got from my time in Sarajevo back in the 1990s – that you should be grateful that you have the opportunity, because lots of people didn’t.”