You don’t have to dig deep into the internet to find people who hate Diane Abbott. And I mean hate: visceral, mindless, cruel, twisted hate, the sort that’s desperate to hurt, that makes you fear for humanity.

In the six weeks leading up to 2017’s general election, nearly half (45.14%) the abusive tweets aimed at women MPs were aimed at her, according to an Amnesty International survey. “The type of abuse she receives often focuses on her gender and race, and includes threats of sexual violence,” says Amnesty.

Labour canvassers in workingclass seats in 2019 reported voter after voter saying they couldn’t vote Labour because Diane Abbott would be home secretary.

“Down with dumb Diane,” screams a headline over a mindless bit of internet bile. “The thickest politician in history… she’s got the sentencing of her criminal son to look forward to for starters…” (In 2020, Abbott’s adult son was in trouble over drug use – he’s better now.)

But when you meet the MP, you’re struck by the charm of her personality, and you can’t come away from a conversation with her believing she’s thick.

Former shadow chancellor, John McDonnell, a close friend, calls her: “A serious politician who also enjoys life. A serious player over many decades, who is always honest, always straight.

“Some people don’t see that because she always does it with a smile on her face. She has a good circle of friends and a quiet, dry sense of humour that can puncture pomposity.”

Even political opponents are often affectionate, although also barbed. One of Keir Starmer’s most senior supporters told me: “She could have had so much to contribute to the party but short termism and courting popularity took over, together with poor judgment. It’s a waste of an able, hard worker with a good heart.”

Abbott is quick, clever, fluent, with a well-stocked mind, which is what you’d expect from her CV. Her parents both left school at 14 to move to Britain from Jamaica.

Her father worked as a welder and her mother as a nurse. Born in 1953, Abbott was a star pupil at Harrow County School for Girls, and went on to take an MA in history at Newnham College, Cambridge.

Up the road at Harrow County School for Boys, and later at Peterhouse, Cambridge, was her contemporary Michael Portillo. They acted in plays together while at school, and appeared opposite each other years later on television, talking politics with Andrew Neil.

The Cambridge historian is never far from the surface. In an article on her website, she attacks Tony Blair and others for criticising president Joe Biden’s decision to withdraw from Afghanistan.

It reads: “Like the Bourbons, they have learnt nothing and forgotten nothing.” She seems to assume her constituents in Hackney North and Stoke Newington will know all about the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in France in 1814.

She became a civil servant, then moved to journalism, reporting for Thames Television and TV-am.

She writes well and has a good broadcasting voice, and if politics had not taken her, she might have had a successful, and less stressful, life in journalism. Instead, in the 1980s, she became a press officer for the Greater London Council and a Westminster City councillor. That’s when John McDonnell got to know her.

“She was dynamic, attractive – all of a sudden, everywhere you went, there was Diane. I thought, ‘wow, there’s a force of nature here’. The media wanted individual targets – it was nasty stuff, vicious, personal attacks – and there was this young Black woman saying: ‘we will not be beaten’.”

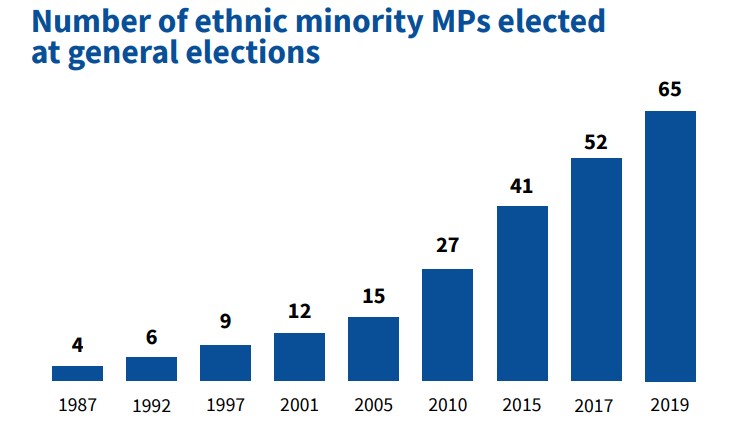

In 1987 she became Britain’s first Black woman MP. Labour strategists worried that her race, her gender, and her left-wing politics might turn a safe seat into a marginal (they were wrong). Her face appeared on the Conservatives’ campaign advertisement: So this is the new moderate militant-free Labour Party.

No doubt the Tories would say that this was because she was left-wing, not because she was Black. After her election, newspapers ran photos of her at the state opening of parliament, commenting on her clothes, her hair, her make-up.

There was no chance of office for an outspoken left-winger in a Blair or Brown government, but her quick wit and experience of the medium made her something of a television personality. She loved appearing on Andrew Neil’s programme. It was a taste, perhaps, of the life she might have had, if she’d restrained her desire to change the world.

She also won The Spectator magazine’s parliamentary speech of the year award in 2008, having risen to talk on civil liberties. “I do not believe, as ministers continue to insist, that there is some trade-off between our liberties and the safety of the realm,” she said.

“What makes us free is what makes us safe, and what makes us safe is what will make us free.”

She was briefly married to a Ghanaian architect with whom she had a son in 1991. When he was 13, she sent him to the expensive City of London School.

It was hypocritical because she had attacked Tony Blair and Harriet Harman for not sending their children to the local comprehensives. Her credibility was seriously damaged.

“I knew what could happen to my son if he was sent to the wrong school and got in with the wrong crowd,” Abbott said at the time. “Once a Black boy is lost to the world of gangs it’s very hard to get them back,” she explained.

Education campaigner Melissa Benn says: “That decision, and an article she wrote praising her grammar school education, has set her apart from the left on education, although she has tried to be a strong voice for the improvement of state education for the Black community and that has to be admired.”

In 2010 she was the left’s candidate for the Labour leadership, which put her in the way of nasty abuse, even by her standards. Ed Miliband won and made her shadow public health minister, but five years later she was replaced by Luciana Berger. That year, Miliband lost the general election and resigned as leader.

The left wanted a candidate who, it was assumed, would come last, and it was hardly fair to ask Abbott to go through all that abuse again. Thus began Jeremy Corbyn’s four-year stint as Labour leader.

Thus, too, began the fracturing of the old alliance. Corbyn, Abbott and McDonnell were now the three tribunes of the left and were close friends (in the Seventies, Abbott and Corbyn had had an affair).

But Abbott and McDonnell could see with clarity how Corbyn’s errors were throwing away the best chance they would ever have – not that they’ll admit it, even now. “When Jeremy was leader, Diane and I knew that our first duty was solidarity, and we backed each other up,” says McDonnell. “We close ranks under attack.” Privately, they were in despair at Corbyn’s handling of Brexit and anti-semitism.

As early as November 2017, Abbott, then shadow home secretary, joined forces with Keir Starmer to kill a Corbyn proposal which would have shelved discussion of Britain’s future relationship with Europe.

Getting this right was key to winning the next general election (the “last shot for oldies like Jeremy and me”). Polls showed Labour Party members overwhelmingly wanted a second referendum, so party democracy demanded that Labour support one, and anyway Brexit was increasingly identified with xenophobia and jingoism, she said.

By June 2018 she was privately calling Brexit “a racist operation”. During a heated shadow cabinet meeting, McDonnell and Abbott warned that a lack of clarity on whether Labour would support Remain in any future referendum was causing severe damage. But Corbyn insisted on delay. Why was Abbott not a reliable support for her oldest friend in politics at the time of his greatest need?

The answer, I think, is that, for all her barbed wit and televisionfriendly persona, she is, like McDonnell, a serious politician, seriously interested in power and in changing the world. Corbyn is not.

During the 2019 general election she did a car-crash radio interview. Afterwards she admitted for the first time that she is diabetic. McDonnell says: “She is a bright woman and that sort of thing that can happen to any politician. It’s the risk you take, especially with [a] ‘gotcha’ interviewer.”

But LBC’s Nick Ferrari didn’t have to push: she fell over. Listening to the recording, you feel her misery and anticipate the glee of the haters. Gifts to her detractors have long been a feature of her career. Earlier this month she tweeted criticism of Starmer for writing a column in The Sun. It didn’t take long for people to point out that she herself had written for the newspaper. There is a danger that such blunders overshadow the politics.

Her attack on Starmer was revealing. Abbott had wanted to give him a clear run as leader, but she now feels he has broken all his pledges and declared war on the left. So it’s back to fractious opposition.

But for the first time, at the age of 68, there’s a sense that she’s weary of controversy. She turns down political interviews saying she’s too busy, but found time for a soft Vogue interview in which the magazine had her try on a lot of clothes.

But she is also bringing on the next generation of young female Labour MPs from ethnic minorities, such as Zarah Sultana, 28, and Apsana Begum, who is 31.

“They see her as someone they can rely on,” says McDonnell. She’s an older woman who has been there, done that and has the scars to prove it.

Francis Beckett is an author and historian who has written biographies of three Labour PMs.