Two men in earnest conversation, perched uncomfortably on chairs by a table on the banks of the River Seine, apparently indifferent to the chill of a murky winter’s day. One is Van Gogh, the other his young friend Émile Bernard.

No doubt they are talking about their work – the scenes they are painting, the techniques they use. Perhaps they have already visited the tavern on the towpath behind them and discussed Bernard’s admiration for Edouard Monet and Toulouse-Lautrec or Van Gogh’s fascination for Japanese art forms.

The pair must have mulled over Georges Seurat and his painting technique of Pointillism, a revolutionary method in which he used tiny dots of pure colours which, with Seurat’s precise brush, created a luminous world alive with colour.

In what is a diverting aside in the history of art, Van Gogh and the Avant-Garde along the Seine at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam highlights a brief moment in the late 1880s when five artists – Seurat, Van Gogh, Bernard, Paul Signac and the lesser-known Charles Angrand – sought inspiration on the riverbanks and the leafy islands of the Paris suburb of Asnières.

By the end of the 19th century the district had become a popular weekend spot for city dwellers eager to swim, boat, dance and relax in cafes, but what attracted the artists, what made it so inviting to them was not so much the country air but the contrast with the fast-growing industrial suburb of Clichy. There it loomed on the opposite bank with its gasometers, cranes and coal barges.

Van Gogh, then only 34, explained to his brother Theo how “the bringing together of extremes gives me new ideas – extremes, the countryside as a whole and the bustle here.”

In May 1887, he began what he called a “painting campaign.” For a few heightened months, he trudged the three miles to Asnières from the hectic embrace of Montmartre or caught the new fast trains which sped him to the city’s outskirts in a mere 30 minutes. There he experimented with brighter colours and bolder brushstrokes and wrote how painters “who didn’t use whole colours, who always worked in grey, do not, with the greatest respect and love, satisfy the present-day longing for colour.”

He worked with typical passion. Signac, who Van Gogh had first met in an art supplies shop, recalled the day they had spent painting together on the banks of the Seine, had lunch at a guinguette, a small cafe with cheap wine and music, and returned to Paris on foot.

“Van Gogh wore a blue zinc worker’s smock and had painted dots of colour on the sleeves. “He stuck right by me, shouting, gesticulating, and brandishing his large, size-30 canvas, so that he spread wet paint on to himself and the passers-by.”

The extremes which attracted him so much are evident in the much-loved By the Seine. At first glance it is a simple view of a man walking along a peaceful, tree-lined riverside, but in a smoky blur on the horizon are the chimneys of Clichy. Again, in Factories at Clichy, the contrast between the red roofs of the factories and their belching smokestacks dwarf a couple strolling in an overgrown field.

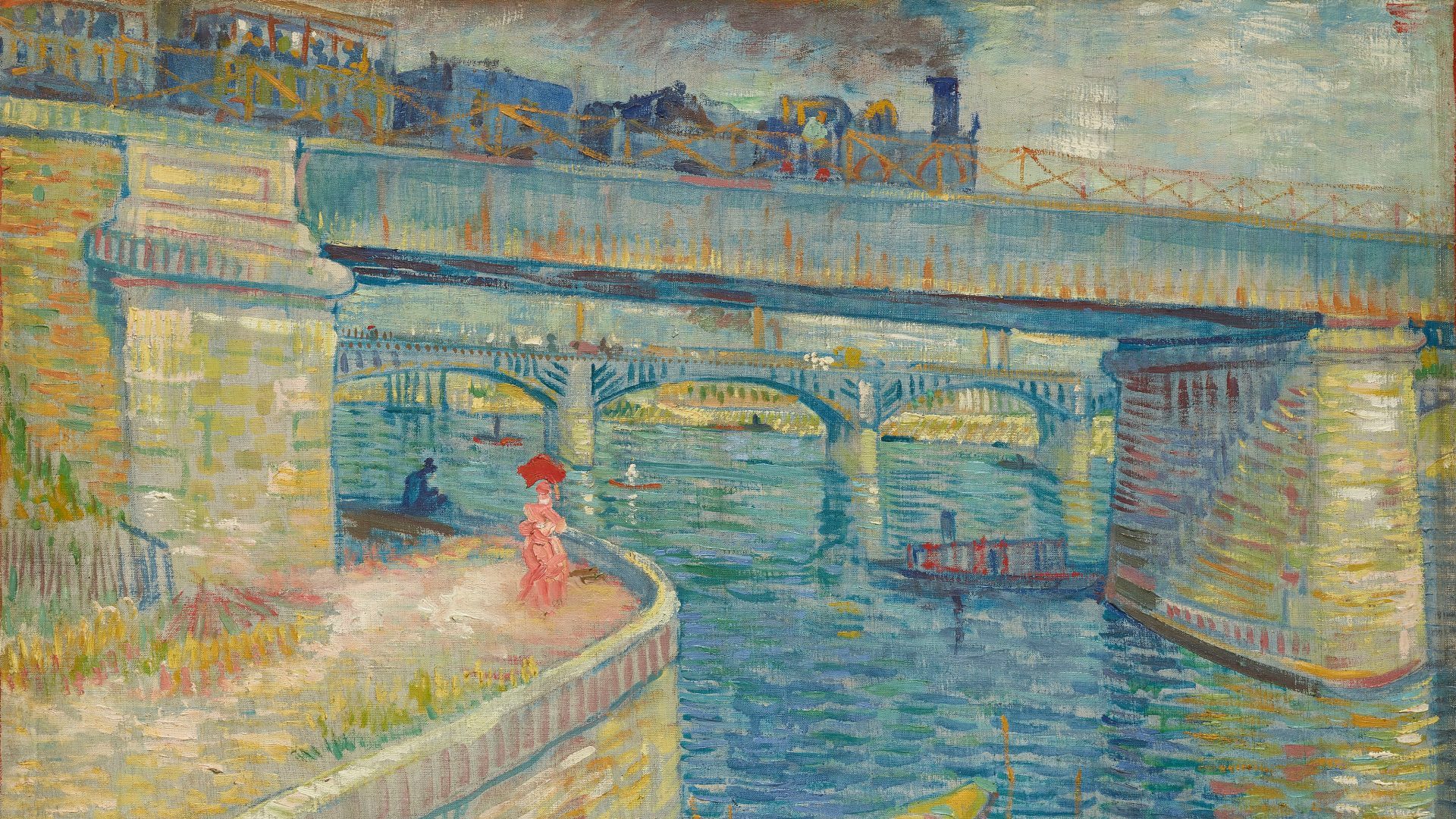

A train steams over the river in Bridges Across the Seine at Asnières, while in the foreground a woman walks with an umbrella along the bank, a fisherman waits for a catch, small boats flit across the water. (An array of black and white postcards from the time emphasise how faithfully the painters interpreted the scene in front of them – however different their styles)

Which is not to say he forbore painting bucolic scenes like the couples in an orchard, a peasant tending his plot and restaurants like the flag and flower-bedecked The Restaurant de la Sirène at Asnières where he might well have shared a bottle with Signac and Bernard.

The latter was enthusiastic about boating, which is reflected in his pen and ink sketches of regattas and the “beautiful, sparkling sail wafting an elegant boat across the blue or green water.”

He thoroughly enjoyed the party atmosphere of La Grande Jatte, the island off Asnières, but also shared Van Gogh’s enthusiasm for depicting the encroaching industrialisation on those sparkling waters.

But his most striking are later works from 1887, in a technique he labelled Cloisonnism, using bold and flat forms separated by dark contours in strong, almost blocky, shapes such as Two Women on the Asnières Footbridge and Iron Bridges at Asnières with its simple outlines of two figures walking past upturned boats, framed by a steam train racing over a bridge.

If Bernard did not embrace Seurat’s Pointillism, Charles Angrand certainly did. He had painted alongside Seurat in his studio and perhaps nothing illustrates that influence more than The Seine at Dawn, a marvellous, floaty view of a lone fisherman silhouetted against the hazy waters of the Seine with the ghostly skyline of Clichy’s factories high on the horizon.

To emphasise how closely his style matched Seurat’s, his painting of The Seine at Courbevoie taken from the same place on the bank at about the same time is hung alongside La Grande Jatte.

Paul Signac did not embrace Pointillism with Angrand’s enthusiasm. At least, not at first. He was shocked when he first saw Seurat’s classic Bathers at Asnières. After all, he had lived in the community for some years and he did not recognise the place from the controlled calm of the painting. Its style is quite a contrast to his early Impressionist influences.

But Signac had come to know Seurat and become increasingly entranced by his innovative methods. The Stern of Tub with the familiar view of the two bridges and a hurrying steam train is painted from a barge, while the opposite perspective from Bow of the Tub is altogether more sylvan with pleasure boats moored by a rocky shore, trees in full leaf and a horizon unblemished by factories.

However striking Signac’s Pointillist works may be – and even though the museum (understandably) gives Van Gogh top billing – it is Georges Seurat who steals the show.

He was the first of the quintet to visit Asnières in 1881 and found the river, the islands, the people and the light gave him the conditions he needed to finesse his ground-breaking technique, moving away from the naturalism of the day to the stylised use of colour and form which is so familiar today but so radical in the 1880s. The complexity of the way dots were used to create a purity of light and shade is both luminous and precise.

Various studies for Le Baignade (A Bather) drawn in 1883 trace Seurat’s progress to the finished version with all its clarity and enigmatic charm. The lads on the river bank sit as immobile as sculptures and apparently oblivious to each other or their surroundings, uninterested in the boats on the river, the smoke in the distance or indeed the sunshine in which they bask.

Similarly, in A Sunday Afternoon on La Grande Jatte, the day trippers stand and sit in the shade of the trees. They are elegant, poised, almost statuesque, and, like the lads, they seem oddly uninvolved with the delights which Grande Jatte offers, as if a display of enthusiasm would be socially de trop.

“Some say they see poetry,” said Seurat. “I see science.”

There was however something poetic about the way he invoked the spirits of Egyptian and Greek sculpture in his work. He wrote: “I want to make modern people… move about as they do on those friezes, and place them on canvases organised by harmonies of colour.”

His paintings transformed the thinking about painting but not to universal approbation. The painting, the painstaking result of many drawings, some on the lids of cigar boxes, was described by one critic as a “mosaic of boredom and image of Sunday misery”.

The public were just as unimpressed and the painting did not sell until Signac held an auction of his work years later, which raised 800 francs. Today it is valued at $650m.

By 1889 all five were moving on in search of new places, new styles and new answers. They were never a group, by no means a movement, but they were young, ardent and united, at least, in their passion for their painting.

Van Gogh had left for Arles in 1888, only to commit suicide two years later at the age of 37. Less than one year later Seurat had died of a sudden illness at the age of 31.

The artist Camille Pissarro, who was at the funeral, wrote: “I saw Signac who was deeply moved by this great misfortune. I believe… Pointillism is finished. But I think it will have consequences which later on will be of the utmost importance for art. Seurat really added something.

Van Gogh and the Avant-Garde along the Seine is at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam until January 14