In Women’s History Month, it is always important to keep in mind something in relation to it: the conundrum of the male genius.

Once, while I was at an exhibition of the work of Picasso, a woman suddenly ran out of the gallery, screaming. All of us in there were concerned, and I and two other women followed her into the women’s toilet to help. She explained between sobs that she was traumatised because all she could see in Picasso’s paintings was his penis.

This disturbed her in a particular work that we were all viewing depicting his lover and muse, Marie-Thérèse Walter. Their relationship, during which they had a daughter, began when she was 17 and he was 45.

She admitted, later in life, that living without him was unbearable. Marie-Thérèse Walter died, after his death, by her own hand. If you know art history, if you love Picasso, you know about Marie-Thérèse and all the other women. And yet…

The gallery story reminds me that, for a long time, Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo was considered the greatest film ever made. This was according to the influential magazine Sight and Sound and its poll of world-renowned critics and thinkers about cinema.

Let me say what my definition of cinema is: it is that art form, on film which, intentionally or not, examines/challenges/celebrates/obliterates/dissects the medium itself.

Every great artist does that to her/his /their medium. A movie is mainly entertainment: sell those tickets, move that popcorn.

Hitchcock, himself, interspersed the words “movie” and “cinema” when talking about the medium; he actually wanted to make movies. Seat fillers; sugary-drink sellers. Because Hitch loved big audiences and he loved money.

He couldn’t give a damn about critics. For him, film awards were for the most part a joke. He was nominated umpteen times for the best director Oscar, but never, ever, won.

Actually, Hitch disdained most film/movie awards because, after all, while an award might give you the chance to make another movie, it tells you zilch about what you need to know inside of yourself, ie: Are you doing it? Have you done what you set out to do?

The man often called “The Master” navigated both worlds – commerce and art. Maybe he thought that the distinction between them does not exist. Maybe he was right.

Hitchcock, like Picasso, “used” women. I put that word in quotes because, if it had been deliberate, totally conscious, neither would have gotten away with it. Most of Hitch’s female actors were street-smart and knew their way around.

He used to say about his muse Grace Kelly: “That Grace! She fucked everybody! She even fucked the writer!” Which, for Hitch, was as low as you could go on the movie-making totem pole.

But I think that women were not full human beings to him, not the way men were. Women were props; justifications and explanations for internal and external male rampage. You can see this spelled out in the 1950s US TV series Alfred Hitchcock Presents, now being rerun on Sky Arts.

Not only is this show instructive in marking the first appearance, as an actor, of John Cassavetes, or a late appearance of the great Claude Rains. You also notice that all of the women are trouble, one way or another.

None of these trouble-making women are that fabled femme fatale “the Hitchcock blonde”. These ’50s women live in aprons and, if not that, fur coats, and are tottering around on heels. It is incredible to look at now, to see all of this.

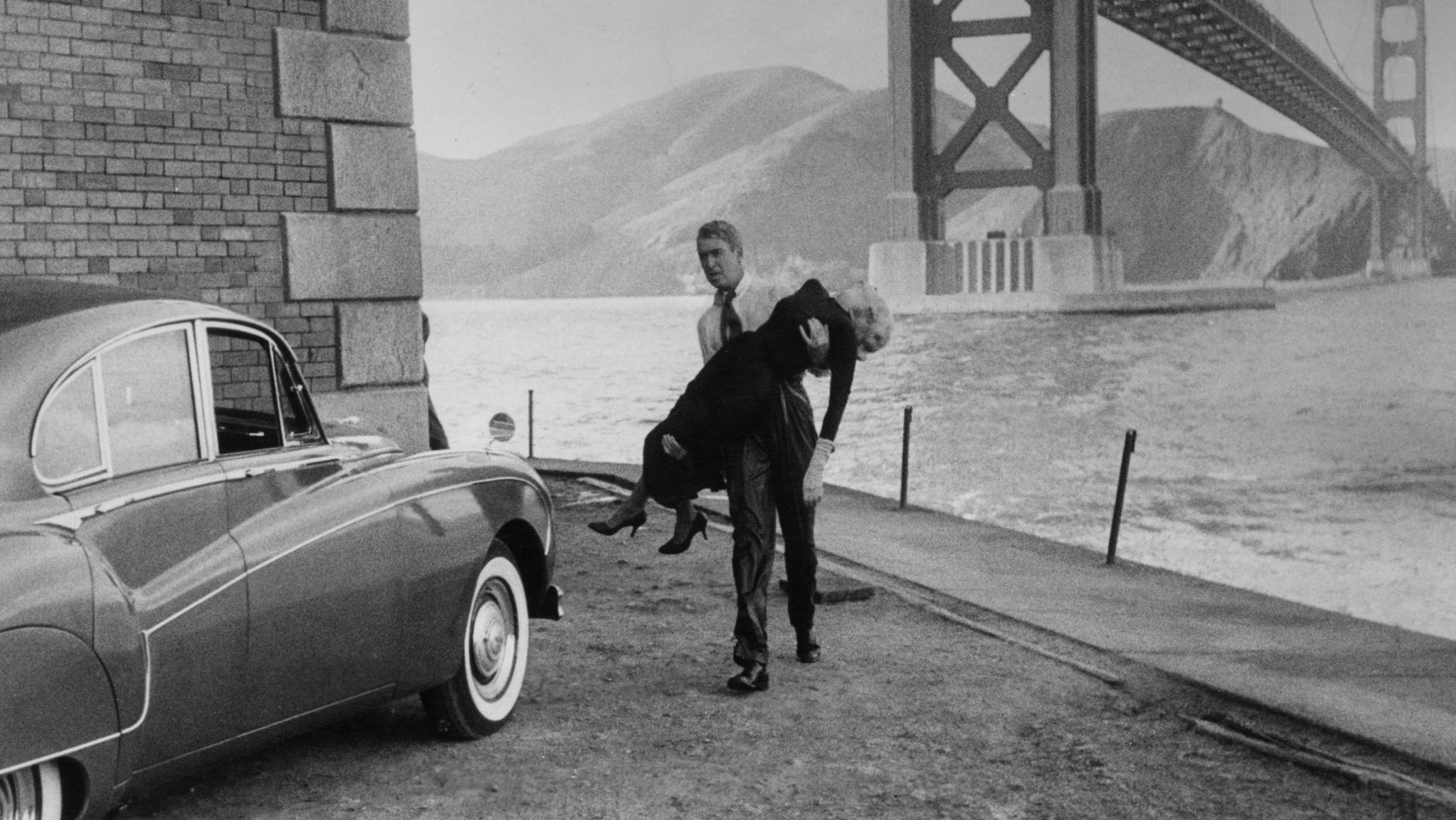

In the midst of this series came Vertigo, released in May 1958, starring Jimmy Stewart as a detective chasing the ghost, or so he thinks, of a woman he has fallen in love with, played by Kim Novak. Stewart and Novak had another picture released at the end of 1958: Bell, Book and Candle, in which Novak plays a sexy witch. No prizes for guessing which of the films broke the box office.

Hitchcock bitterly resented the fact that Vertigo flopped, and blamed Jimmy Stewart for being “too old”. But of course, Stewart, as Martin Scorsese points out, knew Hitchcock very well. Because Hitch is who Stewart plays – a man in pursuit of female perfection – even if he has to kill a female to get it. Female perfection as a cleansing; as The Lost Mother; as the other part of himself: that which society calls “female”. And which is forbidden to him.

The Hitchcock “tells” in this film are legion: it is a masterpiece of a kind of male psyche involving punishment of The Woman and redemption through that. Hitch even shows us Novak’s feet, clad in high heels, as she is being dragged upstairs by Stewart to a tower from which she falls to her death. The last shot is a nun ringing a bell and Stewart’s character standing triumphant, free of the vertigo that plagued him at the beginning of the film. Freed by the violent death of a woman. He is free of vertigo. But not of his pursuit of wholeness. It is all there in colour, with a score by the great Bernard Herrmann.

Hitchcock spills the tea, as drag queens say, about a deep, hidden aspect of masculinity for some: the best woman is a dead woman. No wonder it was considered the GOAT. For many, it still is.

Vertigo’s top place in the Sight and Sound poll was overtaken, in 2022, by a small film, Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, directed by the late Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman. Released in 1975, it starred Delphine Seyrig, immortalised in Alain Resnais’s 1961 masterpiece Last Year at Marienbad. Before Jeanne Dielman she was Edward Fox’s love interest in The Day of the Jackal and the two roles could not be more different.

In Akerman’s film, she is a housewife daylighting as a prostitute. We are in her kitchen with the dreary guys who drop by during their lunch hour to screw her. I won’t even use the words “have sex” because these guys act as if they are relieving themselves. The viewer is left not knowing whether she is having a real orgasm, a fake one, or a cry of disgust and boredom. The movie is deep and devastating. You leave it changed.

Akerman, like Hitch, made cameos in her films. In this, she is a voice in the hallway, on the other side of the door. In the Void. We know and we know that she knows that her “johns” will return to their bourgeois lives. And we watch her return to her routine: washing; cleaning; cooking; waiting: for a man.

Jeanne Dielman deserves to topple Hitchcock as the greatest work of cinema of all time because not only does it erase all jargon about feminism and working-class poverty, it makes us witness; participant and voyeur in the life of a human being subjected to the rigours and humiliation, the fear and the poverty too often visited upon us born with the double X chromosome.

Chantal Akerman never won or was nominated for an Oscar. She once said: “I don’t think woman’s cinema exists”. She is right. Cinema is of itself: a light on what it means to be human. As is a film that never won an Oscar – Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles.

The greatest film ever made.