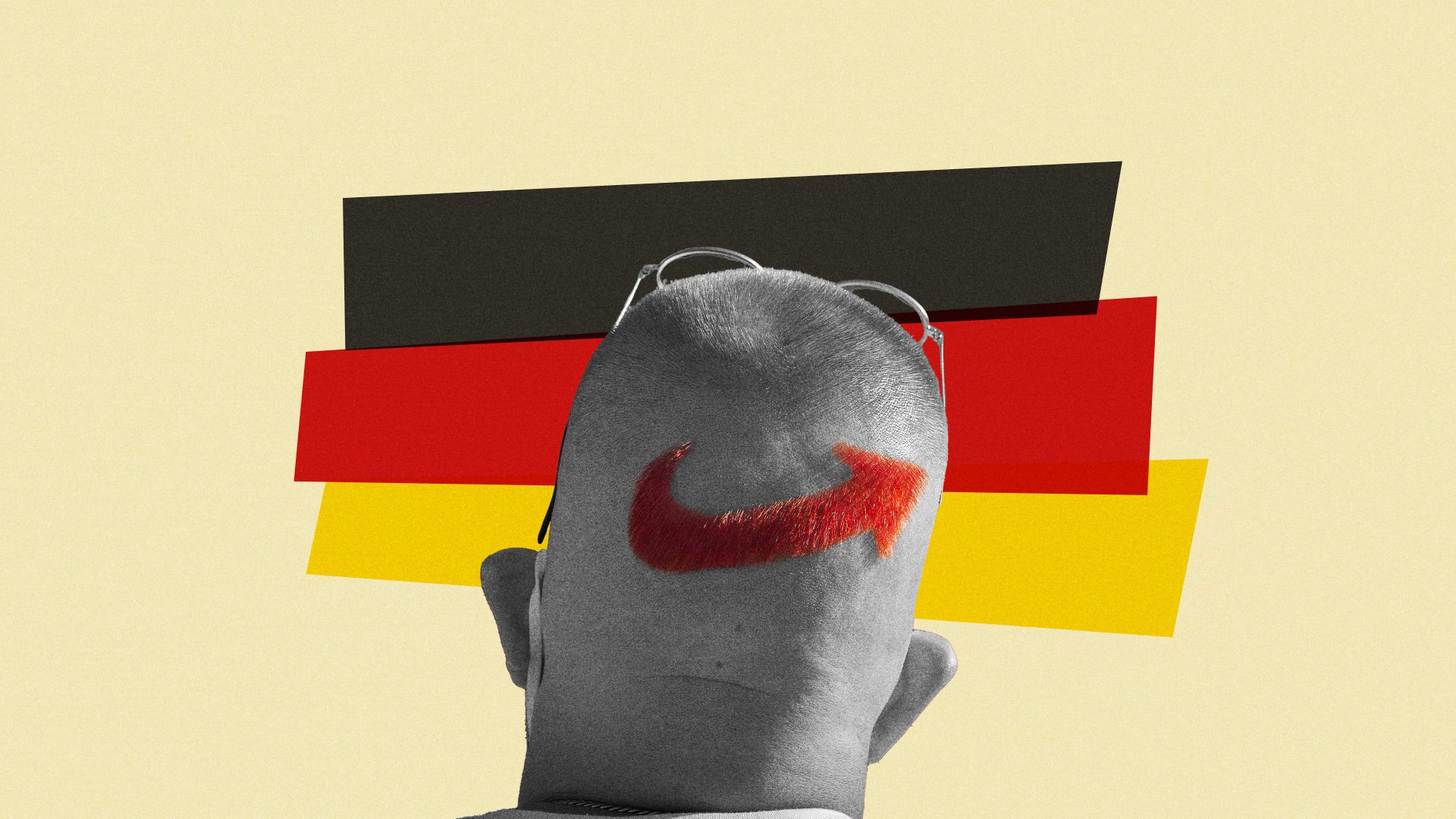

This Sunday could see an alarming political first in Germany. Before now, the far-right Alternative für Deutschland party (AfD) has managed to get candidates elected to parliaments and councils, but they have never once won a governing post.

Next weekend, however, the lawyer and populist Robert Sesselmann could be elected as the new Landrat (head of district authority) in Sonneberg. It’s part of Thuringia in the former East Germany, close to the Bavarian border, and has a flourishing toy industry. And currently, it is toying with handing its executive to the extreme right.

In Germany’s 294 Landkreise (districts), all parties are represented at the top district level, even neutral officeholders – all but AfD. A Landrat is the highest-ranking civil servant, the equivalent of a mayor, and he, too, needs to be elected. In the first round in Sonneberg, Sesselmann gained nearly 47% of the votes. His strongest competitor, the current Landrat, who represents the CDU once headed by Angela Merkel, got 36%.

The second ballot comes at a time when AfD’s poll numbers are at a record high. Since early June, the party is at 18-19%, the same level as chancellor Olaf Scholz’s SPD.

Time to don a sackcloth and sprinkle ashes on my columnist head. Pretty much a year ago I wrote that “it’s too early to celebrate. But AfD looks trapped on a downhill path, straight towards the fate of a radical East German fringe party.” They had lost voters in 11 consecutive elections and were doing poorly in the polls. What has happened since then? Crisis and disenchantment.

Hermann Binkert, founder of pollster INSA, names the core reasons: “AfD is most popular among voters who identify as right of centre. In the Merkel era, the CDU lost a lot of its bonding force towards non-extremist right wing voters. Then there is huge discontent with an in-fighting governing coalition, in which the Greens are seen as the driving force. The most distinct anti-Green party is AfD. And constantly being portrayed as the bogeyman is actually helping AfD.”

On our evening news, people watch chancellor Scholz receiving Giorga Meloni in Berlin and making a return visit to Rome. German media present Meloni as post-fascist, a threat to Italy’s democracy – so of course people wonder why it is OK to talk migration with Italy’s far-right while vilifying the home-grown version.

Binkert’s headquarters is in Erfurt, the capital of Thuringia. His is the only renowned pollster in east Germany. People there, as Binkert puts it, are more willing to openly admit voting for AfD. In the west, the yuck-factor is still prevalent. But shrinking. Two years ago, polls showed that 75% of the German electorate considered ever voting AfD as “unthinkable”. This bulwark has dwindled to 55%.

The party suffering most from AfD’s success will probably continue to be the Christian Democrats. Binkert says: “I wouldn’t have said this two or three years ago, but the momentum for a CDU-Green coalition is gone. The CDU must distance itself more strongly from the Greens and their vastly different Weltanschauung (worldview). They must also demystify AfD while they themselves are still the strongest right wing party.”

This is easier said than done: the CDU is at a steady 29% in the polls. But party chief Friedrich Merz grossly overrated himself when he proclaimed, several times, that he was confident he could cut AfD’s popularity in half.

Is Merz the right person for the job? Binkert has doubts. He fully approves of the Brandmauer (firewall) that the CDU has built between itself and AfD. But he thinks it needs a more left-leaning person than Merz as CDU leader to build bridges to the voters currently eyeing AfD. Because this person wouldn’t raise fears of turning the CDU into some kind of AfD-lite (which would make people vote for the original, as usual).

When it comes to Sonneberg’s election, Binkert criticises the tactic of keeping the AfD in check. All other parties – including socialist Linkspartei – are now endorsing the CDU candidate to prevent an AfD Landrat. “This ‘national front’ may result in the opposite of what they intended. Many voters here will find all-party unity only too familiar, like the GDR.”

But he also warns: “Some people say, ‘let ’em have the job – to publicly fail in office’. But given a strong local administration, failure isn’t at all certain. On the contrary, especially as expectations are so low.

Luckily, AfD remains an Anti-Party, as the pollster phrases it. They aren’t elected because of charismatic leaders, but to give other parties a kick in the shins. And, he adds, it is actually proof that the parliamentary system works: “If voters feel a lack of representation, they fill it. In this case with AfD.” So why shouldn’t other parties close this gap?