For 16 long years, Germany’s Greens scraped a living without government responsibilities, in opposition. A lot of time to muse about how to run things better – and not just better, in fact, but morally superior.

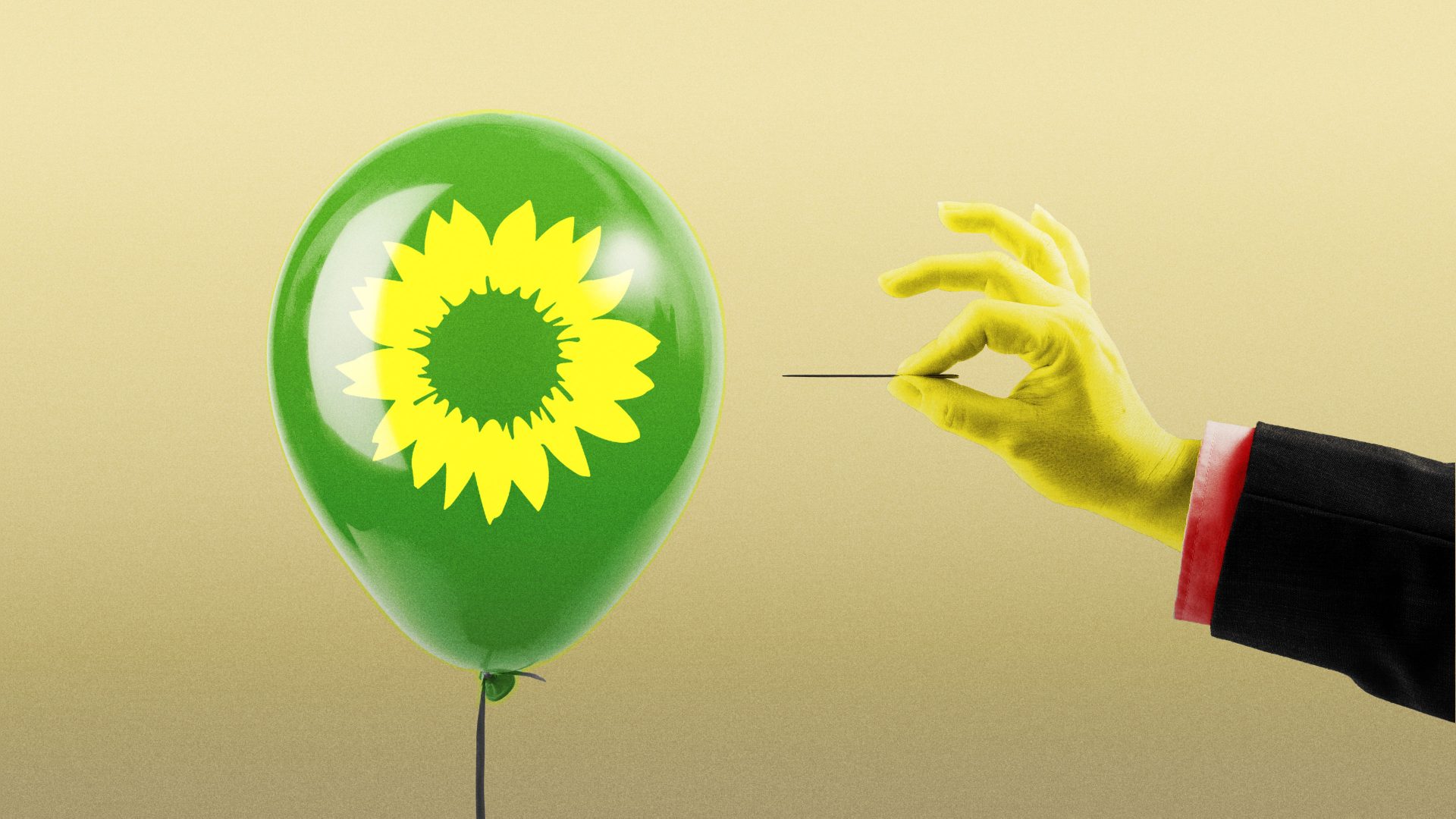

It’s fair to say they raised great expectations. Now, 16 months after entering Olaf Scholz’s coalition cabinet, the fiasco fairy seems to have become a regular visitor, and she is dressed in green.

Take Bremen, where the party just suffered a stunning setback in regional elections. Shortly before polling day, the northern city-state’s Green senator of transport had decided that the popular Brötchen-Taste (bread-roll-button; pressing it gave people a free 20-minute inner-city parking ticket to run errands) was incompatible with saving planet Earth. Voters thought otherwise and ditched the Greens in large numbers (their vote fell by 5.5%). Never mess with Germans and their access to bread…

Shortly afterwards in Berlin, vice-chancellor and minister for economic affairs Robert Habeck lost his best man, because of that man’s best man. The ministry’s secretary of state, Patrick Graichen, had literally promoted his best man from his wedding to run the national energy agency Dena (a promotion revoked once the relationship became public).

Having raised suspicions of cronyism before (see TNE #338), a compliance investigation into Graichen’s work found he had also signed off consulting fees and funding for institutions run by his siblings.

Habeck, having insisted for days that it wasn’t his style to “sacrifice a human being” to boost his own polls, did exactly that a little while later. Too late for a boost, though, his popularity polls are so far down only far-right AfD leaders fare worse. In overall polls, the Greens are even behind AfD.

Sacking Graichen means Green co-chair Habeck must do without his closest adviser, and without the chief architect of the planned transition to a carbon-neutral economy. Graichen was Mr Heat Pump. Now he’s gone, the bill to revolutionise residential heating systems is in danger, too.

This could mean maximum damage for the Greens: They had always portrayed themselves as the guardians of integrity and transparency. With this nimbus demystified, green policy credibility is suffering as well.

“Lost in transformation”, wrote Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung’s influential Allensbach pollsters, who went on to explain that, “consensus in regard to the goal and necessity of a transformation process doesn’t mean that concrete measures to implement it find acceptance as well”.

This is exactly what’s happening at the moment: While a vast majority of Germans are still in favour of climate protection and renewable energy, the proposed measures for residential heating trigger alarm. Heating buildings makes up a third of our total energy consumption. According to statistics, between 70 and 80% of the heat comes from fossil fuels so far. No wonder that 80% of Germans oppose the “boiler ban”: a bill – intending to speed up the shift to heat pumps, solar panels and hydrogen boilers – forbids households to install new gas and oil heaters from January 2024. Instead, new heaters must be run with at least 65% renewable energy.

Of course, this would reduce Germany’s imports of natural gas, too, after decades of depending on energy supplies from Russia. And it makes sense in general because the price of fossil fuel-based heaters will increase significantly in the next few years, once the EU’s emissions trading scheme is extended to buildings.

But so far, the Green boiler ban is solely regarded as massively interfering with people’s lives: 72% are against the scheme that forces homeowners to swap all fossil heating systems to renewables by 2045.

Consumer advocates criticise the ministry’s planned deadline – six months from now – as too tight compared with the UK, pointing to a shortage of skilled workers to install new systems. There is equal concern about an unforeseeable financial burden for homeowners and tenants, despite boiler upgrade incentives.

Unlike Britons last winter, Germans aren’t confronted with the “eat-or-heat-choice” (yet), but 58% believe they will face higher bills because of some measures to increase energy efficiency. It easily costs up to £29,000 to install a heat pump; a maximum of 40% of that sum could be subsidised.

So, it looks like minister Habeck will have to up his game in regard to transparency of costs, timelines and communication. Now that he is under fire because of the nepotism scandal, he signalled his willingness to find a pragmatic solution – in other words: extended deadlines.

This would also ease the pressure on producers like Bosch. At the moment, they encounter a phenomenon very different from what the Greens wish for: a sudden surge in demand for oil heating systems, before the deadline runs out.