Some columns don’t age well. In February 2023, I wrote that I was amazed that Suella Braverman’s Rwandan relocation plans hadn’t caught on with the German far right.

No one seemed keen on the idea of outsourcing asylum procedures to third countries. “Rwanda isn’t an option for us,” I wrote.

Eighteen months later, and without a single asylum seeker deported there, the UK’s plan seemingly is now an option for Germany. In late May, CDU opposition frontbencher Jens Spahn inspected Hope Hostel in Kigali, where UK migrants are set to be housed.

Spahn is promoting a UK-style deal for the EU, and as a gift for the Rwandan president, Paul Kagame, he brought along an official European Championship football.

Of course, it will take more than that; but the notion is taking root in Deutschland. “Ruanda ist möglich” (Rwanda is possible) read the op-ed in the centre-right Frankfurter Allgemeine last Sunday.

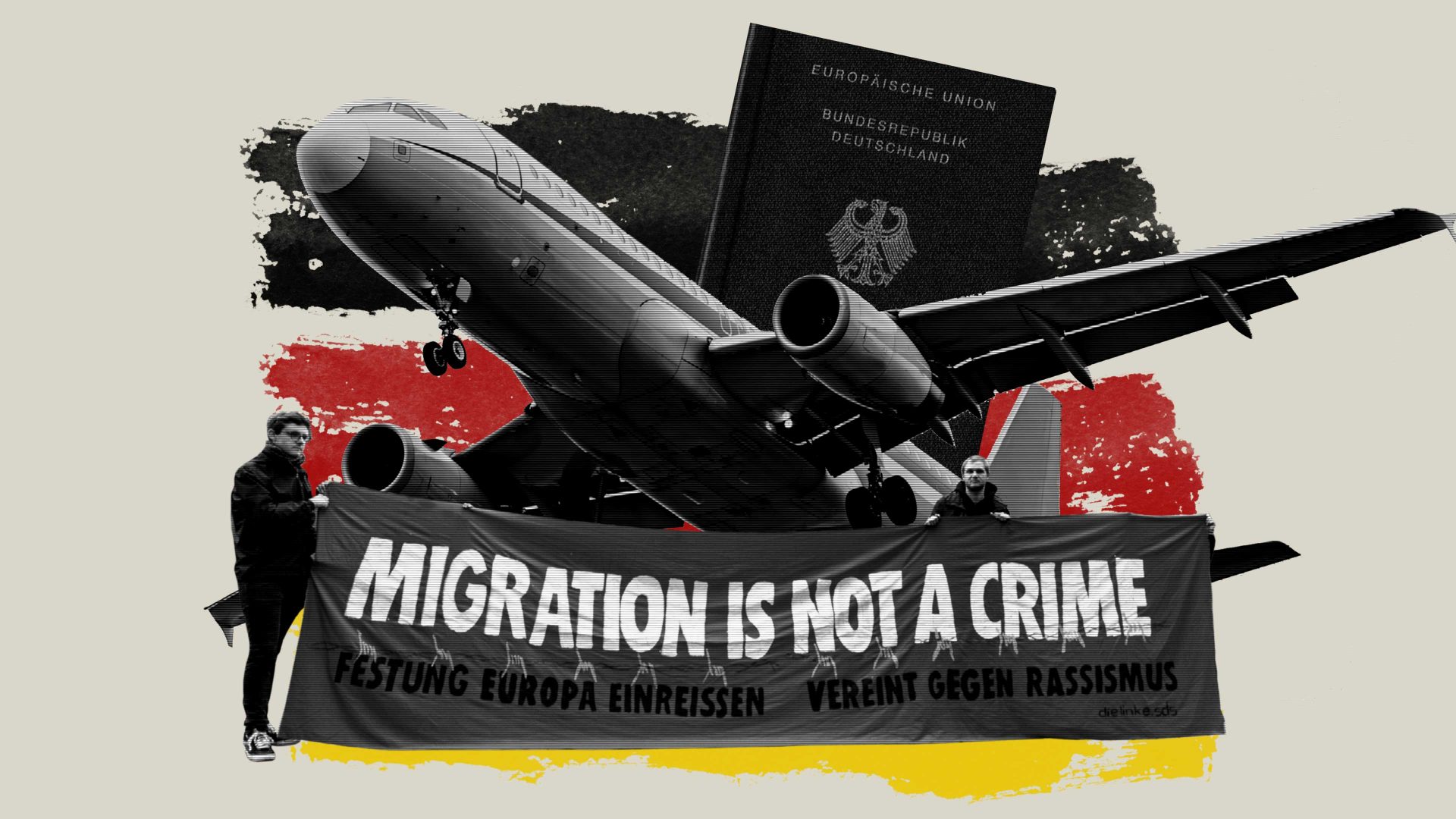

And although the ruling centre-left-green government isn’t embracing the idea, there’s no uproar either. They are desperate: migration has become a hot-button issue again for voters.

While 67,337 people sought asylum in the UK last year, a 17% drop from 2022, Germany saw 352,000 asylum applications, up around 50%. Against the current climate of near-recession, this is fanning social tensions.

Germany has become an economic underperformer. We’ve plummeted from 6th to 24th on the latest IMD Business School’s World Competitiveness index, and the bad news keeps coming. Gaping holes in the health and care budgets, soaring housing and electricity bills, companies folding or moving abroad, infrastructure crumbling – and as always, people are looking for someone to blame for their blahs.

To stop the finger-pointing at themselves, some politicians have taken a swing at Ukrainian refugees. “It doesn’t make sense to talk about how to best support Ukraine and at the same time to pay for Ukrainians who have deserted their country,” said the CDU interior minister from the state of Brandenburg.

A total of 1.3 million people with a Ukrainian passport live in Germany, around 260,000 of them men aged between 18 and 60.

Nein, Germans aren’t expecting them to pick up a rifle and start killing Russians. Instead, people wonder why, in the UK and Ireland, about 50% of Ukrainian refugees are now in the workforce, about 60% in Poland and more than 70% in Denmark – while here, more than two years into the war, only around 24% have jobs, despite a severe labour shortage.

Officials from the FDP, the business-orientated coalition partner in Berlin, are now suggesting that Ukrainian war refugees should no longer receive Bürgergeld. This benefit, recently rebranded “citizen’s money” (despite being passport-blind) and raised by the government, already triggers tensions.

The basic monthly allowance of €563 (£476) plus housing, electricity and healthcare costs means that, by comparison, people who work 40 hours a week often have only a few Euros more to spend than those who don’t work at all. Asylum seekers receive less at €354 (£299), but their numbers also strain the budget.

Last October, Olaf Scholz (SPD) announced “deportations big style”. This month, the chancellor called for criminals and potential terrorists to be expelled, even to countries such as Syria and Afghanistan. Now, all 16 state prime ministers – across all parties – are pushing him and his government to review concrete models for asylum processing in third countries; results due in December.

UK-style Rwanda or Italian-style Albania – there still is significant scepticism. Interestingly, the Social Democrats and Greens are debating moral, practical and financial obstacles, not so much legal barriers, despite UK court rulings. They know that it was Germany, and more particularly the Greens, who blocked a broader third-country asylum approach in EU legislation – which could easily be overturned, given that countries on the EU external frontiers especially are very much in favour.

One big question mark remains, however: if word gets around the world, will third-country asylum procedures really have the deterrent effect legislators hope for?

Ironically, while a Labour government in the UK will most probably scrap the Rwanda scheme after the election, our social democratic government now calls third-country processing of asylum claims a “building block” in German migration policy.