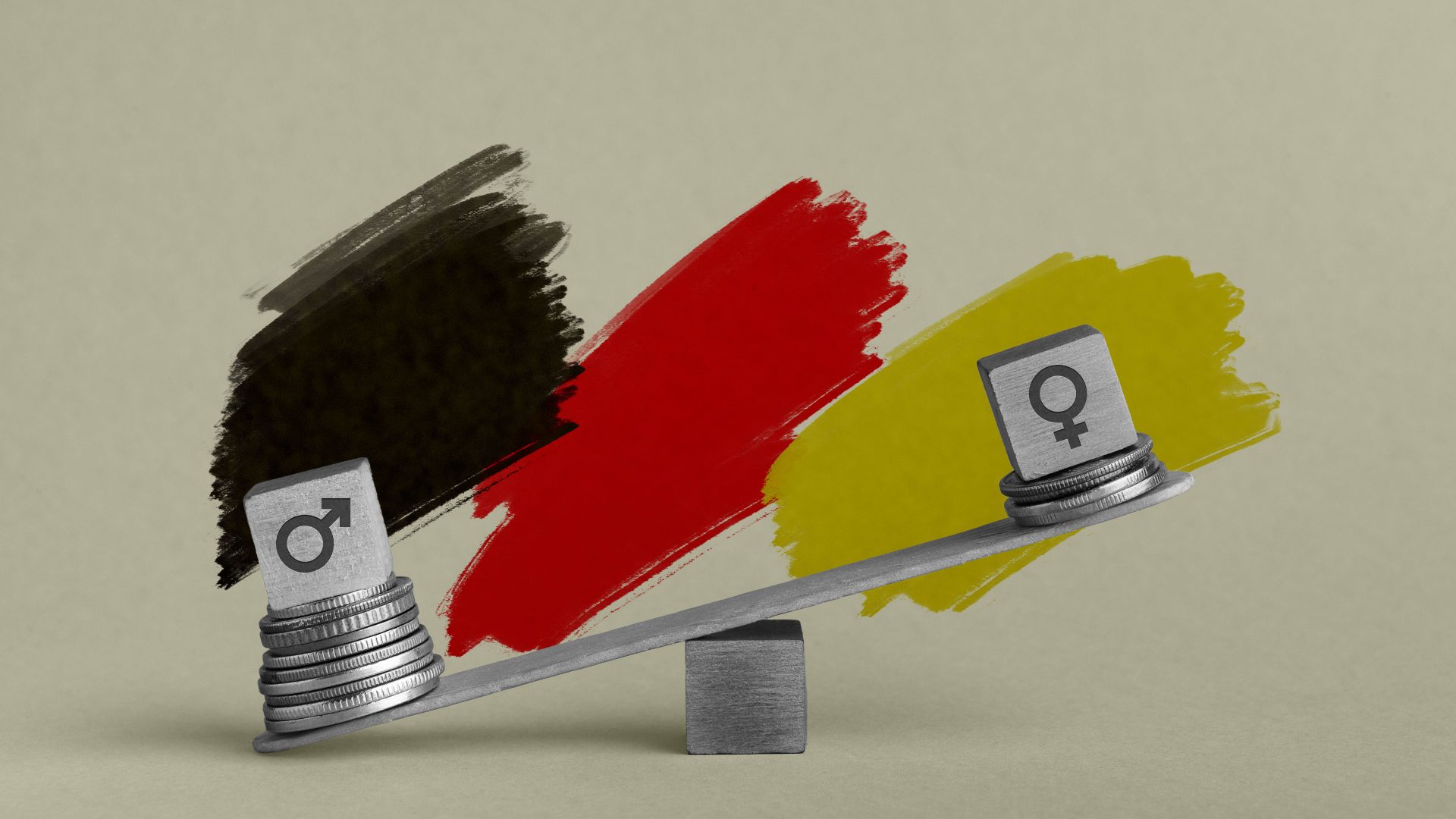

Not long now until World Women’s Day 2024 – it’s on Friday March 8 – and the perennial discussion surrounding the gender pay gap.

Equal pay for equal work should unquestionably be a given, yet sadly isn’t. However, I can’t help but cringe when, year after year, the news bombards me with the statistic that women in Germany earn around 19% less than men, consistently failing to mention that this figure is unadjusted.

Once you account for factors such as weekly hours and years of experience, the true gender pay gap dwindles to between 5 and 7%. Which is still disheartening, but stems from different reasons, which I’ll delve into later.

The core issue is that German society – I should really say west German society – has cultural and structural issues regarding working women. And the annual chorus of outrage (Discrimination! Glass ceiling! Old boys’ clubs!) hasn’t produced any change so far. Finally, however, a government initiative addresses one major root of this problem: our tax system.

Culturally, from 1950 on, when the real income of an average worker’s family already surpassed prewar level, a mentality took hold amid the West German Wirtschaftswunder (economic boom) wherein the status of a family, or rather: a man, was measured by his ability to support a stay-at-home wife. This wasn’t unique to Germany, by the way, and had little to do with Hitler’s rhetoric of childbirth as “the battlefield of women”.

In socialist East Germany, the landscape was starkly different, although not necessarily favourable for individual women. While they were a welcome addition to the workforce and childcare was a state priority, they were still expected to fulfil traditional domestic roles.

Fast forward seven decades, and the German tax system continues to mirror the mindset of the 1950s. True, many countries have a system of joint taxation (the UK opted for individual in 1990), but none is as extreme as the German Ehegattensplitting (spouse-splitting).

Here, after marriage, three-quarters of couples chose the combination of: tax class III: high net income and low tax, as all tax allowances from both partners are deducted (for example, twice the basic tax allowance of €11,604) and tax class V: low net income, high tax

I say “chose”, but the incentive to do so is close to imperative. I won’t bore you with the maths but splitting reduces a couple’s overall tax debt, as long as one spouse earns significantly more than the other. If both earn well, they may as well not be married, it doesn’t really make a difference taxwise.

In the high-and-low-income marriage, however, the higher earner will have even more monthly net pay, whereas the low earner (remember, their tax allowances go to the spouse) sees even less on the bank statement.

Predictably, we find 83% of men in tax class III and approximately 90% of women in class V, mostly working part-time. Remarkably, in no other OECD country do women with children contribute as little to household income as in Germany: below 25%. A fact exacerbated by tax class V leaving so little left from gross income that it makes the contribution appear even lower.

Women therefore think long and hard about whether it is worthwhile to return to full-time work after maternity leave. The immediate financial calculus clearly favours earning little to nothing, particularly when considering extra childcare costs for those who do work.

The long-term benefits such as enhanced career prospects, independence and improved retirement pensions are often overlooked (and I’m not even getting into the power dynamics in some marriages depending on who earns how much).

Statistics reveal that in Germany, the income of mothers a decade after their first child is born remains 60% below the pre-birth income. In contrast, this figure is only 20% in Denmark and Sweden, and 40% in the UK and the US.

The good news: The German government plans to abolish tax classes III and V, while maintaining the overall annual benefit. This should translate to higher monthly incomes for many women, potentially incentivising greater workforce participation (dearly needed in times of labour shortage).

However, the sobering reality, is: a gender pay gap will persist, and globally, unless women form a habit of negotiating. Or in the unlikely case of men stopping to do it.

Biases and institutional sexism undoubtedly exist, but research suggests that a lower income also has a direct connection to women refraining from asking for pay rises. So, here’s a quick book recommendation, for women and men alike: Getting (More Of) What You Want by Stanford-emerita Maggie Neale.