“Dear Mutti, how are you?” reads the slightly misspelt letter in a kid’s handwriting, pencil-written on a long and narrow strip of paper which has yellowed through time. “I have received your 2 letters. I am healthy. Your bellyache is gone, isn’t it? Mutti, I think you need bread. I’ll go to Block 3. I have just about enough for myself. So please don’t worry about me. I hope we will soon be together again. If I have bread, I will send it to you, you know that, Mutti.”

The author was 11-year-old Sigfried Rapaport, nicknamed “Sigi”. His family lived in Hanover until 1938, when the Nazis deported his father Moritz-Moses to Poland. They lost track of him. Sigi’s sister Resi was saved by a Kindertransport to England in 1939. But Sigi, his siblings Paul and Paula, and their mother Miriam, were deported to the Riga Ghetto in 1941.

Paul was then sent to the extermination camp Auschwitz-Birkenau. Miriam, Paula and Sigi were deported to the concentration camp Stutthof. This is where he wrote the lines to his mum in 1944 – a year before he was killed, aged 12, on one of the death marches.

His mother succumbed to typhus. Only Paula and Resi survived and later entrusted their brave brother’s letter to Yad Vashem – the World Holocaust Remembrance Center, in Jerusalem.

It is now on display in the German Bundestag, as part of the exhibition Sixteen Objects – 70 Years of Yad Vashem, which commemorates the centre’s creation in 1953.

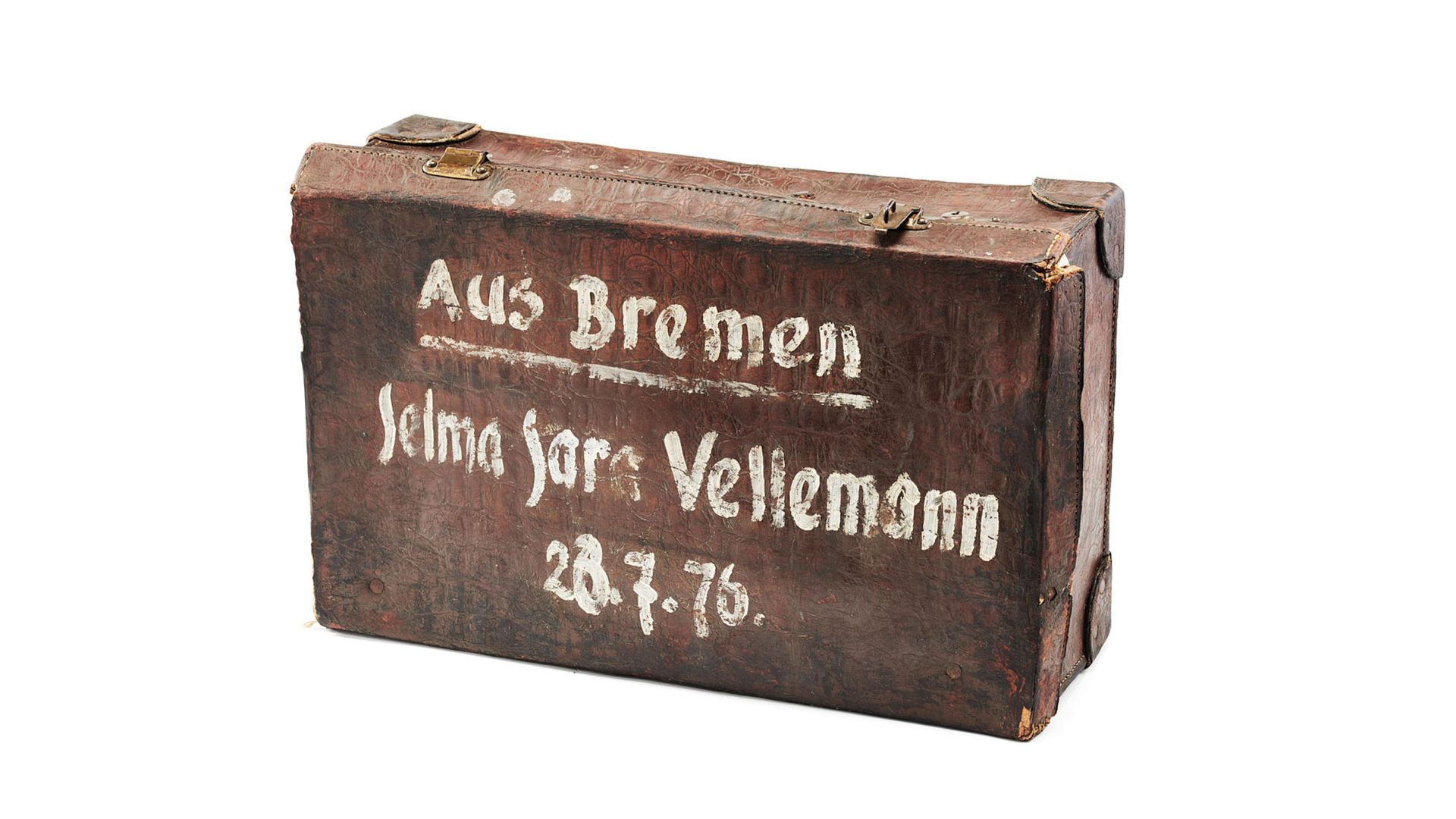

The 16 objects, representing locations in each of the 16 Bundesländer, Germany’s 16 states, are evidence of an identity destroyed in every German town during the Shoah.

“I was looking for a variety of objects, not just Jewish artefacts”, says London-born and Berlin-based curator Ruth Ur. “Because this is foremost about Germans.”

Among the exhibits from Yad Vashem is a ceramic miniature kitchen, a toy that Anneliese Dreifuss from Stuttgart could take with her when she was fleeing to the US with her father and sister.

There is a poetry album, once belonging to Lilo Ermann from Saarbrücken, who was killed in Auschwitz with her parents.

And a black piano, from Chemnitz in Saxony, which 15-year-old Shlomo Margulies managed to ship to Haifa in 1939 – while also acquiring tickets for his family, somehow managing to save their lives.

A doll named Inge was a farewell gift to four-year-old Lore Stern from Kassel, who left Germany for the last ship from Portugal to New York in 1941.

Lore Mayerfeld, now 85, was a guest at the opening of the exhibition in Berlin. She told the audience, in fluent German with an accent from the central state of Hessen, that her own children and grandchildren were never allowed to play with Inge – who is dressed in the pyjamas Lore wore on November 9, 1938, when Nazis demolished her father’s shop. His parents, Lore’s grandparents, who gave her the doll, didn’t survive the Holocaust. To cherish their memory, Lore donated Inge to Yad Vashem – as one of 42,000 objects in the collection.

“At home Inge can only serve to remind me and my family of the atrocities we witnessed and endured, but at Yad Vashem Inge can tell our story to the world,” she said. “This is why I go to Germany. To tell my story and the stories of the six million who were murdered by the Nazis and their collaborators and who they tried to erase all evidence and traces of their existence.

“These objects are witnesses to their lives and their stories that they never had the opportunity to tell.”

Each of the 16 artefacts is unique. They share a dignity that goes directly to the heart. They also share a history of persecution, each belonging to someone who was once a normal member of German society – until this same society turned against them.

They have now returned to Germany for the first time. There’s another first: Dani Dayan, Yad Vashem’s chairman since 2021 (only the third person to occupy this post, and the first one born after the second world war), came to Berlin to open the exhibition.

As a young man, Dayan had sworn never to set foot on German soil. Not because of hatred, he told me, but as his way to remember the Holocaust. Like the Jewish tradition to leave a piece of the house unrendered, to remember the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem nearly 2,000 years ago. Not to travel to Germany was his unrendered bit of the world map. But because of his new position, the 67-year-old felt that to come to Berlin served the same goal: to keep the memory alive.