It’s official: justice – or rather, liars in robes – has proven blind indeed, blind to women’s needs. This is about the US Supreme Court, of course. And, more generally, about a society’s capacity to compromise.

Roe v Wade wasn’t a compromise. And nearly 50 years later, the landmark decision backfired. Donald Trump has sadly proven to be a better strategist in this matter than his predecessor Barack Obama.

Shortly after the news broke, French president Emmanuel Macron emphatically posted: “Abortion is a fundamental right for all women. It must be protected.” Your prime minister Boris Johnson called it a step backwards: “I’ve always believed in women’s right to choose and I stick to that view.” And Bundeskanzler Olaf Scholz tweeted: “Women’s rights are threatened. We must defend them resolutely.”

Interestingly though, in Germany, there is no such thing as a woman’s “right” to terminate a pregnancy. To this day, unless it has been caused by rape or is endangering the woman’s health, abortion is rechtswidrig (against the law) and section 218 of the Strafgesetzbuch (penal code) states the maximum penalty is a prison sentence of up to three years.

But here’s the compromise: section 218a gives impunity as long as the abortion is within the first 12 weeks of the pregnancy and at least three days after compulsory counselling.

Unlike in the UK, not all counselling agencies have to be strictly impartial but may counsel on behalf of the unborn child. And because there is no right to abortion in Germany, there’s also no NHS paying for it (unless rape was committed or there are medical reasons why the pregnancy should be terminated). Women have to bear the cost of €300-700 themselves. Only if they can prove they are in a dire financial situation will the health insurance pay.

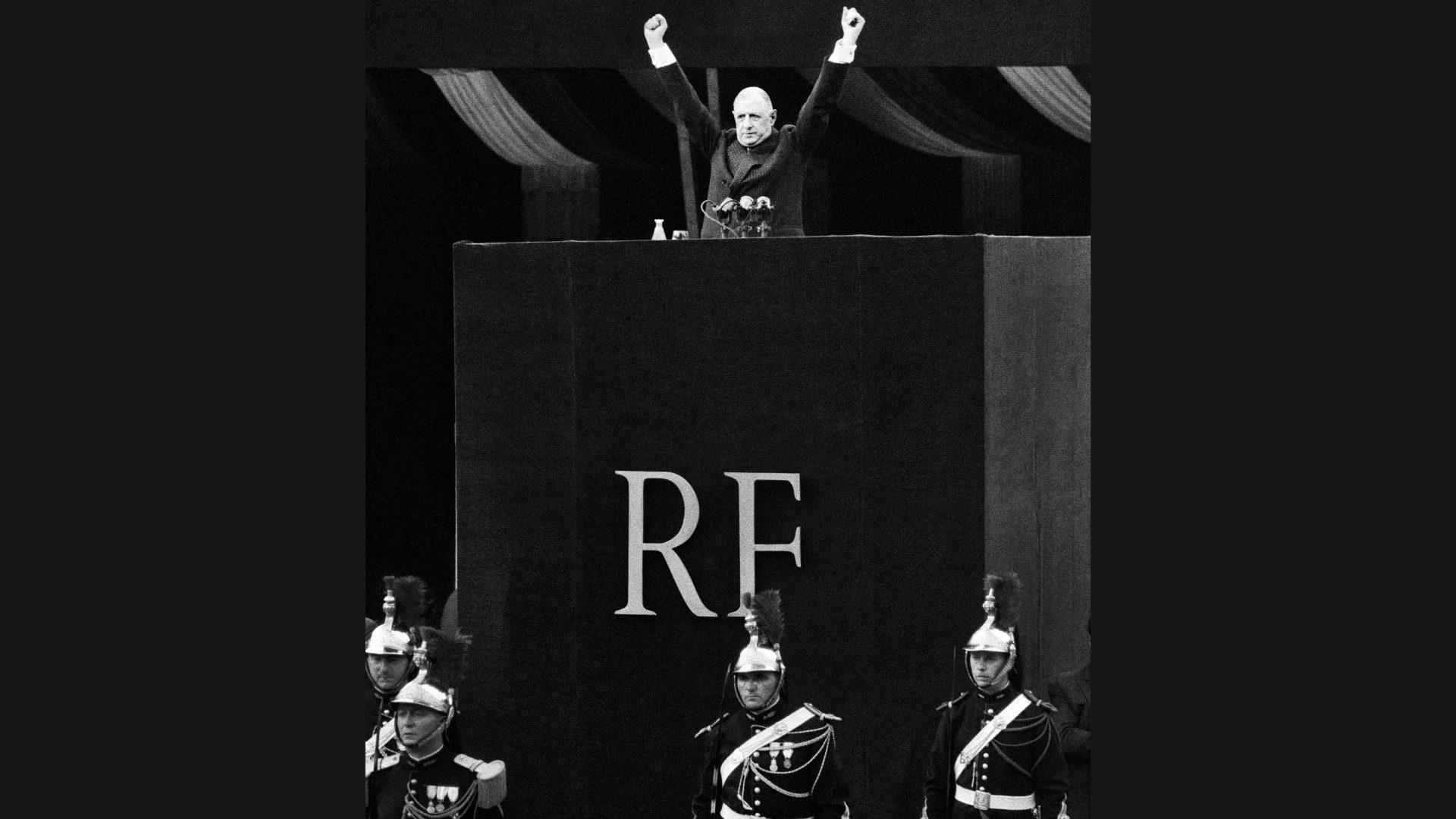

There have been attempts in West Germany to legalise abortions. But the constitutional judges in Karlsruhe never went nearly as far as the US Supreme Court in 1973.

And so, section 218 StGB remained highly disputed. Women’s rights groups created the slogan “Mein Bauch gehört mir!” (literally: my belly is mine!, loosely “my body, my right”). There were high-profile criminal cases against doctors who carried out abortions. And a by now famous Stern magazine cover in 1971, with the title “Wir haben abgetrieben” (“We’ve had an abortion”), listing 374 women by name who had spoken out.

Eventually, chancellor Willy Brandt’s government pushed through a legislative reform with a narrow majority, legalising abortion within the first 12 weeks.

The Bundesverfassungsgericht quashed this law in 1975. The German Grundgesetz, it argued, only states the fundamental right to live, no right to terminate life (however early the stage may be). The court defended those who cannot fight for themselves, unborn children, over defending women’s rights to choose.

With German reunification, things needed to change: the GDR (illiberal as it was in most other aspects) had more liberal abortion laws than the Bundesrepublik, and today’s legislation – section 218a – is a mix of the two. The debate around it and the solution have since pacified society, political parties and interest groups (not the extreme ones, as usual), but issues remain.

On Friday, the government majority in the Bundestag scrapped section 219a – a law which criminalises doctors advertising or providing medical detail about the abortion methods they use. So it’ll be easier for pregnant women to receive information. But it is still growing more difficult to get an abortion.

On the German Medical Association’s search site, the map of Germany shows a lack of abortion facilities in rural areas and in the (more religious) south of Germany. In 2003 there were around 2,050 abortion facilities, by 2020 numbers were down to 1,100 – a reduction of more than 40%. In some parts of the country, women will have to travel more than 62 miles to find a doctor or clinic.

The reasons range from doctors retiring (there are reports about 75-year-old MDs still carrying out abortions because otherwise no one would in their area) to fewer doctors actually wanting to terminate pregnancies (now contraception and the morning-after pill are widely available), to medical staff backing off because of threats and abuse. The Medical Association recently demanded that government must do more to protect them against pro-life activists and a climate of fear.

Pro-choice activists, in Germany too, still see the need for a more liberal abortion legislation. In all probability, abortion in Germany will continue to be treated differently from any other medical procedure, because of its fundamental character. Allowing it in practice while prohibiting it in theory isn’t strictly logical. But it makes sense.