Stonehenge is such a familiar part of our heritage it has become almost a tourist cliche. Our picture is of druids gathering twice a year at the newly installed stones to mark the solstices – the summer one fell this week – and performing rites of celebration as the sun creeps up, over the rim of the plain’s horizon, then shines through the stones so carefully, so mysteriously, set to align with its rays.

It would be an indelible image, were it not for the fact that druids only came to Stonehenge many, many years after its megaliths.

Now in its last weeks, the British Museum’s revelatory exhibition, The World of Stonehenge, makes clear that there is much more to discover about the monumental stone circles that have loomed above Salisbury Plain for 4,500 years. As the curators, Duncan Garrow and Neil Wilkin, explain, Stonehenge itself “acts as a useful gateway and reference point for exploring the chronology of this ancient world”.

Despite its familiarity, then, Stonehenge is a world of secrets and surprises. It is part of a complex heritage involving different peoples and their cultures from across Europe who made their way to Britain at the end of the Ice Age between 15,000 and 10,000 years ago.

The exhibition invites us to marvel at primitive tools – axes of green jadeite stone with such luminous, elegant quality that they might even have been treated as decorations; mace heads painstakingly decorated with swirls and spirals. The most spectacular, found in Knowth, Republic of Ireland, is carved from a piece of flint and seems to have a face, which is remarkable given there was almost no figurative art at the time.

There are carved stone balls covered with spirals, triangles, geometric lozenges and butterflies. The same symbols are seen in three solid chalk cylinders referred to as drums, which were found in a grave in Yorkshire in which the remains of three children were found, holding hands. Poignantly, on two of the drums, eyes have been carved in what was, perhaps, an attempt by grieving parents to protect the spirit of their children in the next world.

Remembering the dead was important to the living. Stonehenge was originally a cemetery area, as hundreds of burial mounds and graves in the area testify, and each one has a story that helps to explain the interplay of cultures and movement of the people. Few more than the so-called Amesbury Archer, whose skeleton was excavated in 2002 to reveal enough evidence to suggest that he was 45 years old, had died in about 2350BC and had journeyed from the Alps, bringing with him magical skills as a metalworker.

Around the body were an astonishing collection of artefacts, probably placed there by mourners in recognition of his status, including copper knives, wrist guards, gold ornaments, a small anvil used in metalworking, four boars’ tusks, two knives and 18 arrowheads.

But if the cemeteries of Stonehenge are about death and the afterlife, it is

the seasons, the sun and the heavens that define the place. It would have

been instinctive for the people to look for cheer at the darkest time of the

year – the winter solstice – by gathering to pray that the cycle of the seasons would be reborn.

There is a hint of that life-affirming moment in the eerie ruins of Seahenge, which lay buried for 4,000 years in the salt marshes of Norfolk until 1998. On a much smaller scale than Stonehenge, it has a similar circular shape but is made of wood, with an oak tree upturned in the middle as a symbol of a powerful life force reaching to the cosmic realms. There are marks of 51 axes on the gnarled timber, which may have been wielded by 51 different people. Maybe the whole community came together to build their place of worship.

Attached to one fork-shaped timber is what can only be described as a door. Open it at the time of the solstice and the light floods in and on to the upturned oak tree root in the same way as the sun lights the stones on Salisbury Plain.

Seahenge was completed around 2500BC at about the time the last building in Stonehenge was erected, and it coincides with the arrival of gold, a new way of reaching for the gods. Thanks to this new material, the people no longer had to gather at the same place at the same time each year; instead, the priest or chief of the community was able to wear the symbols of the sun and directly reflect his connection to the heavens.

And fabulous they are, sun discs made of gold picked out with circles, zigzags and crosses, and of sheets of crescent-shaped gold known as lunulae, which were hammered waferthin and worn as a collar. The fringes were decorated but the central area was always left clear of embellishment and polished like a mirror, to reflect light on to the face of the wearer.

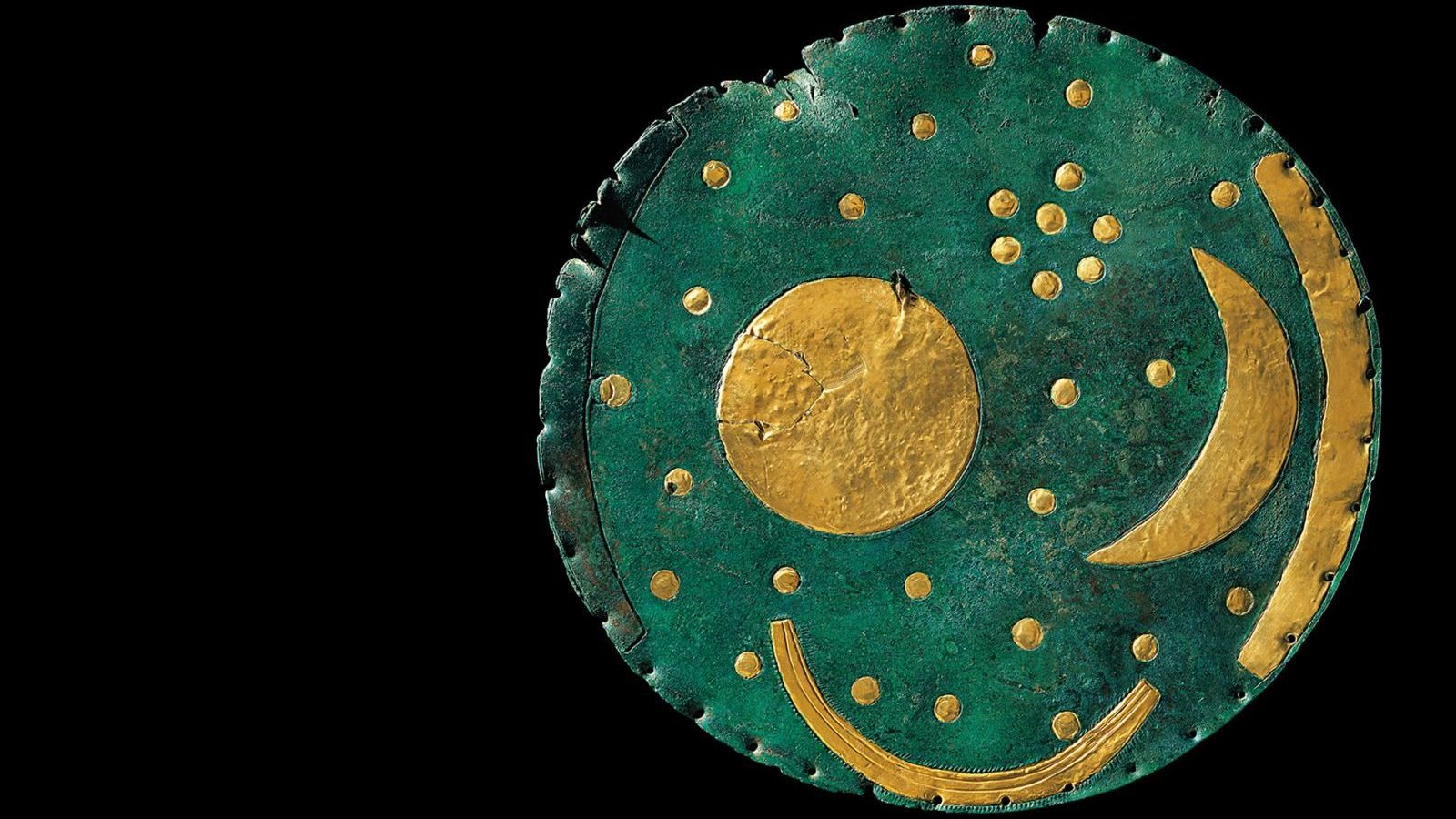

Another dazzling object, the Nebra Sky Disc from eastern Germany (c1800), is set on a disc of bronze with the sun, a crescent moon, an arc that signifies the solstice, a scattering of stars, and at the bottom a ship set in gold leaf. Such imagery provides an insight into the astonishing knowledge of the universe these apparently primitive cultures had acquired.

By now (1300-1150BC), the graves are revealing signs of a growing hierarchy, with a wealthy elite buried with their finery. Sophisticated necklaces known as torcs, forged out of bands of gold and bronze, looped and gilded with patterns, were evidence of their conspicuous consumption. By now Stonehenge has lost its influence, international trade is growing, and the drift from the plains of Wiltshire to the coast is under way.

The show ends with a gleaming pendant, the Shropshire Sun, (c.1000-

800BC), discovered in a pond in 2018. A glorious object, it is covered on one

side with geometric decorations, sun motifs and triangles that are almost

art deco in appearance. It is a fine way to end the exhibition, but maybe a trove of tiny gold boats embellished with suns might be more fitting. It is

as if they are sailing away from the stones of Salisbury Plain on a Homeric

adventure to new worlds.

The World of Stonehenge, British Museum, until July 17