The New York meeting last week between Liz Truss and the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, achieved precisely nothing – not even a thawing of the distrust the EU has for the British government, according to diplomats.

EU leaders still think it is not worth trying to be flexible with Britain, because there is no reward for them in it. Whatever they do, they will still be the government’s Aunt Sally, so why should they be flexible? As for the British government, Labour strategists worry that it may be pursuing a “scorched earth” policy that will leave Labour in government with an even bigger mountain to climb.

The statement after their meeting tells us that Truss and Von Der Leyen agreed that Putin was bad and Ukraine brave – hardly a breakthrough. “They also discussed UK-EU relations including energy, food security and the Northern Ireland Protocol,” it says blandly.

Privately, EU diplomats admit the stark truth behind the careful diplomatic language. “Trust is the biggest issue,” one of them told me. “There is no trust in the British government.”

They didn’t trust Boris Johnson, and now, the EU ambassador to Britain, João Vale de Almeida, told his reception at the Labour Party conference, “you have a new prime minister, which we noticed.” He hoped it might be the start of a new relationship, but so far “things have not changed”.

He also commented on “the good quality of our relationship with Labour” – an unusual thing for a diplomat to say of the opposition party. This might just be because he was in Liverpool for Labour’s conference. Then again, it might not.

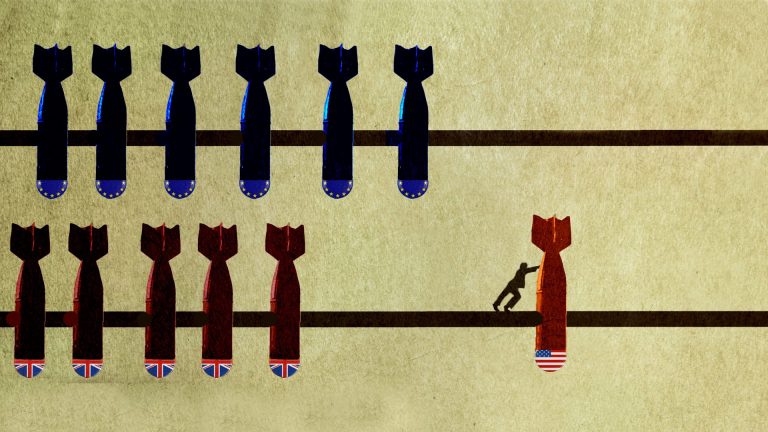

If Britain’s relations with the EU are worse than they have ever been, those with the US are hardly any healthier. Public signs of dissent include President Biden’s pointed attack on trickle-down economics and his repeated warnings about the Northern Ireland Protocol, but private signals are even more disturbing.

I understand that following the AUKUS debacle – the security cooperation agreement between Australia, the US and the UK that caused outrage in France – the US hurried to put things right with Europe by sharing intelligence information wholesale with European countries – but not with the UK, its traditional ally and the country that likes to talk of its “special relationship” with the US.

Labour now expects to inherit a parched diplomatic desert after the next election. So its leaders are already busy travelling around Europe telling the continent’s leaders that Britain will, by 2024 at the latest, have a government they can trust and do business with.

To Sir Keir Starmer and the shadow foreign secretary, David Lammy, that seems to be the realistic objective for them to pursue. They are not thought to believe that a return to the EU is possible at any foreseeable time, or even in their lifetimes. But they can, and they hope they will, create a co-operative relationship with Britain’s nearest neighbours.

They do not think that will be easy, because they will start from such a low base. The purpose of Europe for Liz Truss appears to be as a kind of all-purpose villain, there to allow her to court cheap popularity in the Tory shires.

The longer this goes on, the higher the mountain will become that the next Labour government has to scale. Starmer worries that Truss will – for example – abandon the working time directive, which would make a return to good relations even harder, and issues like cross-border crime and migration even more difficult to resolve.

That’s his ambition. It seems a dreadfully tame ambition to many Labour members. Why – they ask – should Labour give up on the idea of rejoining the EU, when it is increasingly clear that the voters are starting to realise the dreadful error they made in deciding to leave?

The policy is not going to change this week, or this year, but the anti-Brexiteers are not going away. They will continue to will talk about rejoining, but the Starmer government will be about diplomacy.