Filthy water everywhere, without warning; scores of people dead, lives and livelihoods devastated. The quantities of mud are simply beyond comprehension; the emergency response slow, disorganised, and completely inadequate.

An eyewitness account of the floods that devastated Florence in 1966 is back in print for the first time since 1967. As Spain comes to terms with its own floods, it makes a horribly familiar read.

October 1966 had been exceptionally wet in northern Italy, and by the evening of November 3, the new month was already promising much worse. In Florence it was a night “for a hot bath and a cognac, bed and a good book, with the sound of the rain drumming on the shutters a comfortable soporific.”

As she made her diary entry that evening, the American writer Kathrine Kressmann Taylor, best known as the author of 1938 novella Address Unknown, could hardly have anticipated what would confront her as she opened the shutters the next morning, the rain still drumming away. In fact, nobody could: Florence had not flooded for over a century, and even then, the city had escaped unharmed, the waters confined to lower ground further down river.

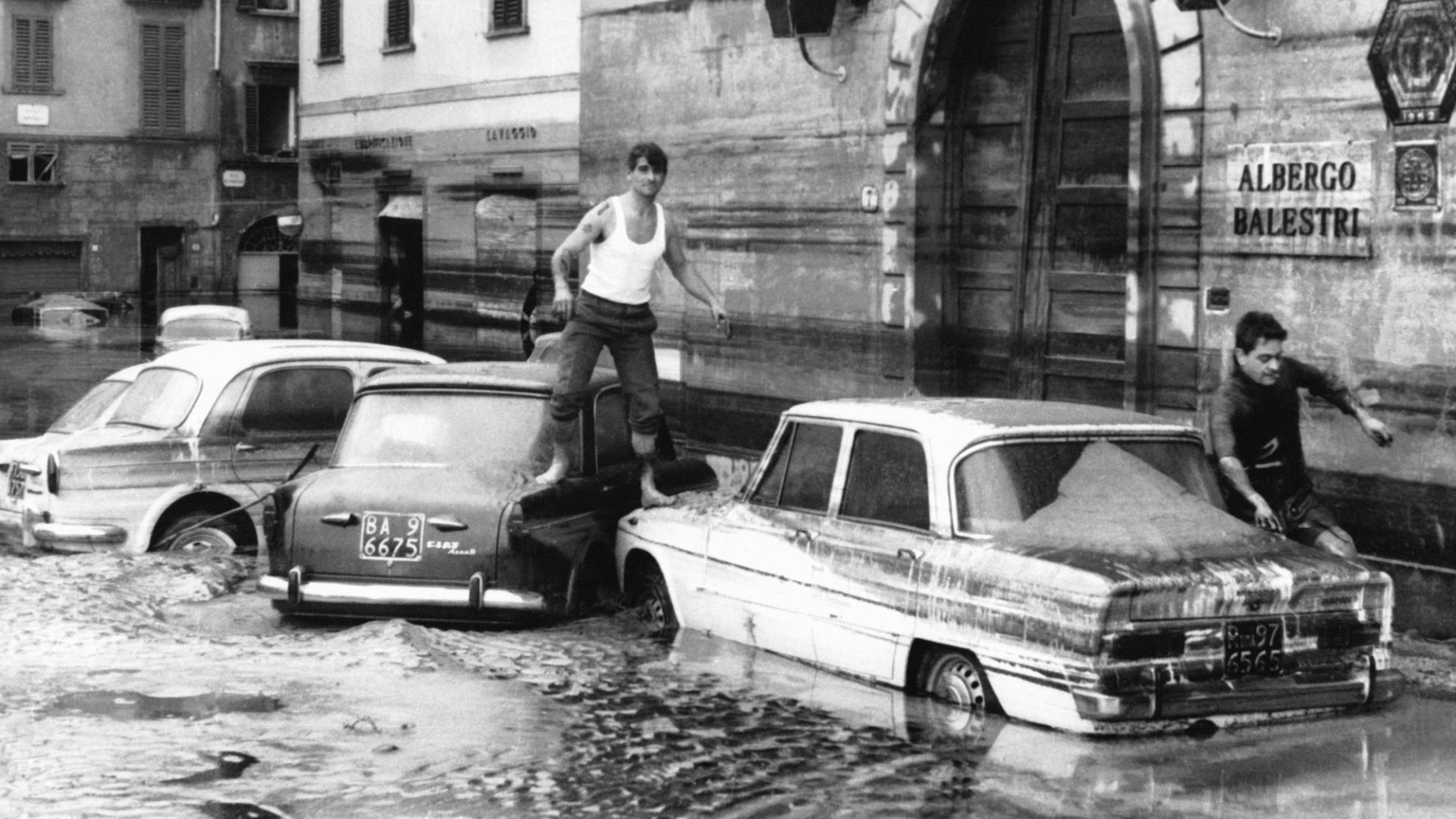

But at dawn on November 4, the Arno, “ that peaceful green stream”, was “a snarling brown torrent of terrific velocity, spiralling in whirlpools and countercurrents that send waves running backward,” she wrote. Awakened from its normally placid state, the river had become a ferocious rampaging beast, ripping through the city with extraordinary force.

As she counts its victims – an uprooted tree, branches, oil drums – Kressmann’s reaction moves through shades of astonishment, horror, awe and even a sort of surreal amusement, as “a whole series of playful grey and red gasoline cans” rush past. A “child’s red ball” adds a stab of melancholy, followed by “a chair sailing serenely, its arms and carved back above water and holding steady and upright as if inviting someone to take a seat”. It’s only as she catalogues the bric-a-brac that she realises its meaning: somewhere up river, a house has been devastated.

Despite the horrors outside, inside Taylor’s pensione, all is calm – the Arno “runs full” every autumn, says the Signora, it’s just the high waters escaping to the sea. Her confidence, Taylor soon discovers, is shared by many Florentines, and the depth of their shock and bewilderment as the extent of the devastation is revealed, is one of the most moving aspects of this book, in which Taylor documents in diary form the flood and its aftermath, in which more than 100 people died.

First published in 1967, Florence: Ordeal by Water has been out of print ever since, but now – as floods bring misery to central and south-west Europe – it is available again in a special new edition published by Manderley Press, with a new cover design and an introduction by Vanessa Nicolson, author of a novel, Angels of Mud.

In seven concise, pacily written chapters, Taylor charts the four-month period from the flood to the following spring, when against a rosy sunset, she measures terrible loss against the “bright-faced students”, affectionately called angeli del fango (mud angels) who helped to rescue the city’s unique cultural heritage, and the bravery and dignity with which the Florentine population (“by no means generally patient”) faced their ordeal.

For Taylor, the experience cemented her attachment to the city she had moved to aged 63, recently retired and a widow for more than 10 years. Sprinkled with Italian phrases, and as vividly descriptive of the city as of its people, the book offers an amusingly American perspective on Italian ways, from “the customary breakneck way of Italian driving”, to the concern for “the right ordering of the household”, of which chiefly food.

The Signora, and her small staff at the pensione are satisfyingly drawn, and remain just on the right side of caricature: when the Signora eventually becomes concerned, it is not because of the threatening river, but because the morning bread has not arrived. Among the guests is a university professor from Los Angeles, and it is thanks to him and other Americans that various sensible interventions are made, such as filling bathtubs while fresh water is still available.

Italian idleness and disorganisation come in for considerable prodding, though Taylor is steadfastly loyal to her Florentine comrades, as the lack of government aid forces them on to their own resources.

A woeful response from Rome, whose radio bulletins announce that Florence was “alla normalità”, contrasts with the distraught appeals of Piero Bargellini, the mayor of Florence, who asks: “How is it possible to remove this liquid mass with hand shovels?”. The mud, later calculated at 500,000 tonnes, and the oil – “Where did it all come from, we ask, this tide of petroleum?” –is everywhere.

Some of Taylor’s best and most compelling writing describes the plight of shopkeepers, wiping mud from cans and bottles; the Piazza della Repùbblica plastered with sodden paper; “a sticky heap of fine handbags in snakeskin, calf, and suede, wallets and purses, oil-drenched and half buried in a deep paste of mud”.

But despite such bewildering destruction, people were busy with brooms and shovels, and Taylor describes their “solid realism”, as with what sounds very much like the “Blitz spirit” the British like to claim as their own, “people are steadily going to work instead of sitting down and howling their woe”.

Though it had survived for hundreds of years, the city’s unique cultural heritage perished as readily as the livelihoods of shopkeepers and artisans, and Taylor’s description of a car jammed high up between the Duomo and the campanile, is an astonishing prelude to the discovery of Ghiberti’s bronze doors, ripped from their settings. It’s a particularly sombre moment – these ancient doors, called “the doors of Paradise” by Michelangelo, were in place decades before his birth in 1475, and mark one of the great moments of the Renaissance.

A policeman has tears in his eyes, a scholarly type remarks that the flood had achieved what previous, deliberate attempts had not, when during the war, attempts to remove the panels to save them from German looting were abandoned because no one could loosen them.

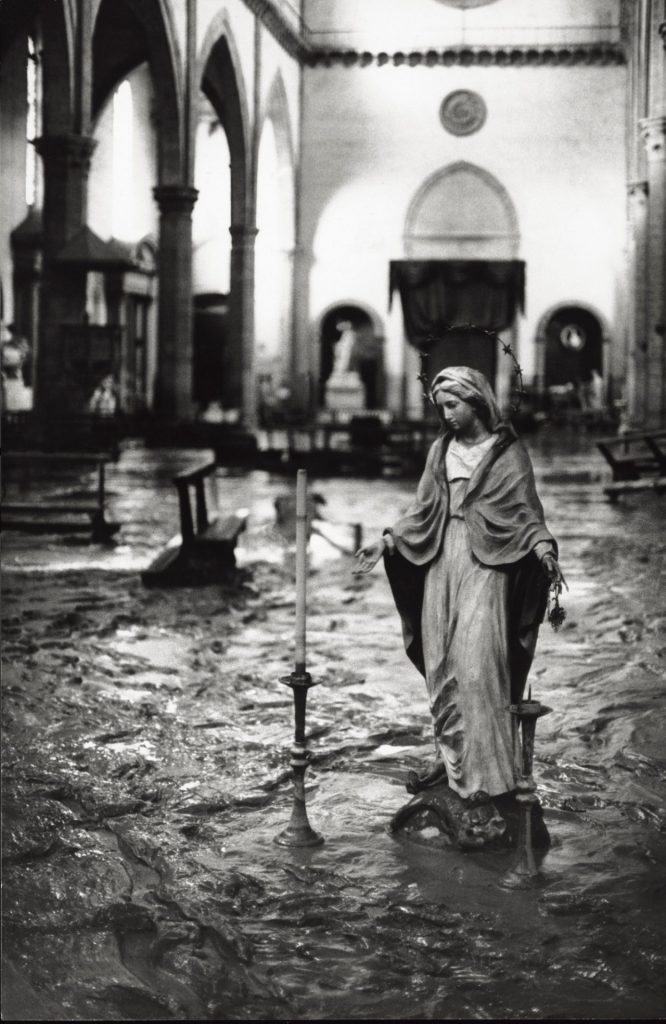

The litany of damage goes on and on – innumerable books in basement stacks of the National Library, the ancient musical instruments of the Bardini Museum, the cloisters at Santa Croce, the Medici Chapel, but it is matched by the extraordinary stories of the angeli del fango: “Casual and joking and singing and working like dogs, they are the first solid and trustworthy and uncomplaining helpers to arrive.”

Soon, the mud and stagnant, foul water began to present serious problems, and the students salvaging books from the National Library wore gas masks, while the authorities distributed chlorine tablets to purify the water, and administered vaccinations against typhoid.

The clean-up operation was one of the most remarkable ever mounted, and was the catalyst for many developments in conservation methods and techniques, including the foundation of the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, one of the world’s foremost centres of art restoration. Today, conservators know better how to save frescoes in situ, and over the past 20 years, the National Library has been securing books and documents in plastic wrapping.

Such measures are becoming increasingly necessary and urgent as extreme weather becomes common. The 1966 flood, matched on the same day by a similarly unprecedented catastrophe in Venice, was caused by a combination of torrential rain and the opening of a dam further upriver.

Prior to 1966, the city of Florence had gone centuries without such an incident, but as apocalyptic floods devastate Spain, northern Italy is once again in recovery mode, following the effects of Storm Boris last month. France, southern Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia have also suffered catastrophic floods this year, likewise the UK to a lesser extent.

Shocking and salutary, Kathrine Kressmann Taylor’s book has never been more timely; as a study of what can be achieved by people united in determination and dedication to a cause, it’s an inspiring and reassuring read for difficult times. But what was back then assumed to be an exceptional event, unlikely to recur for generations, now feels as if it is dangerously close to being normalised.

Thirty-two years after the Rio Earth Summit, what have we done? Globally, our consumption of fossil fuels has gone up, not down – the appetite for gas-guzzling vehicles is as sharp as ever, while plastic production and disposal is on the rise. And what about the people whose lives are destroyed and even lost as a consequence of extreme – but no longer freak – weather events?

Taylor’s book tells us of people’s resilience, but it should also make us fiercely angry that after warnings followed by disasters, and then more, ordinary people continue to suffer the consequences of governments’ refusal to face up to the climate catastrophe. With COP29 days away, it’s time to act.

Florence: Ordeal by Water by Kathrine Kressmann Taylor, introduced by Vanessa Nicolson, published by Manderley Press manderleypress.com; £18.99 hardback