“The history of modern painting from 1910 until our own time could be summed up in a few names: for example, Picasso, Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia”. So begins an article dated Saturday 15, February 1947, full of praise for Picabia the “multi-faceted artist”, cut out from a French newspaper, and pasted into the scrapbook kept by the artist’s wife, Olga Mohler Picabia.

Of that short list, Picasso and Duchamp remain uncontroversial choices, even if his personal conduct has left Picasso languishing in the box marked “problematic”. Love them or loathe them, few would dispute the importance of Picasso, or Duchamp – but Picabia?

As young unknowns in Paris, their similar names and Spanish heritage meant that Picabia (1879-1953) and Picasso were endlessly muddled up, probably more to Picasso’s irritation than Picabia’s. Today, Picabia presents a gnarly problem all of his own, not least because in our age of habitual ironising, his mischief-making nihilism is not shocking, nor particularly suspect, but the imprimatur bestowed on a bona fide artist.

In that vein, Picabia made a pretty poor start, as a late and rather dismal Impressionist who took his views from postcards rather than brave the elements à la Monet. It was as a Dada original that he made his name, the movement’s absurdist tendencies providing the template for a lifelong modus operandi summed up in his often-quoted bon mot: “If you want to have clean ideas, change them like shirts.”

But, though his bizarre machine drawings brought him recognition after world war one, Picabia’s prominence came sooner and by stealth. As the only member of the Paris avant-garde rich enough to have travelled to New York for the revelatory 1913 Armory Show exhibition, he was uniquely available for interview: this is how history is written.

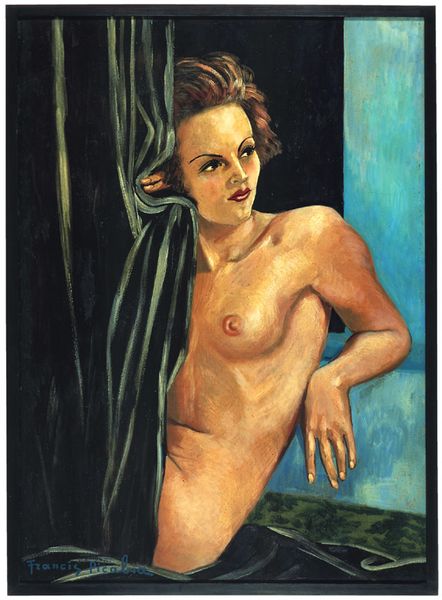

He deservedly fell from favour after world war two, during which he produced some troublingly Aryan nudes, based on photographs from soft porn magazines. He is also known to have made anti-Semitic remarks.

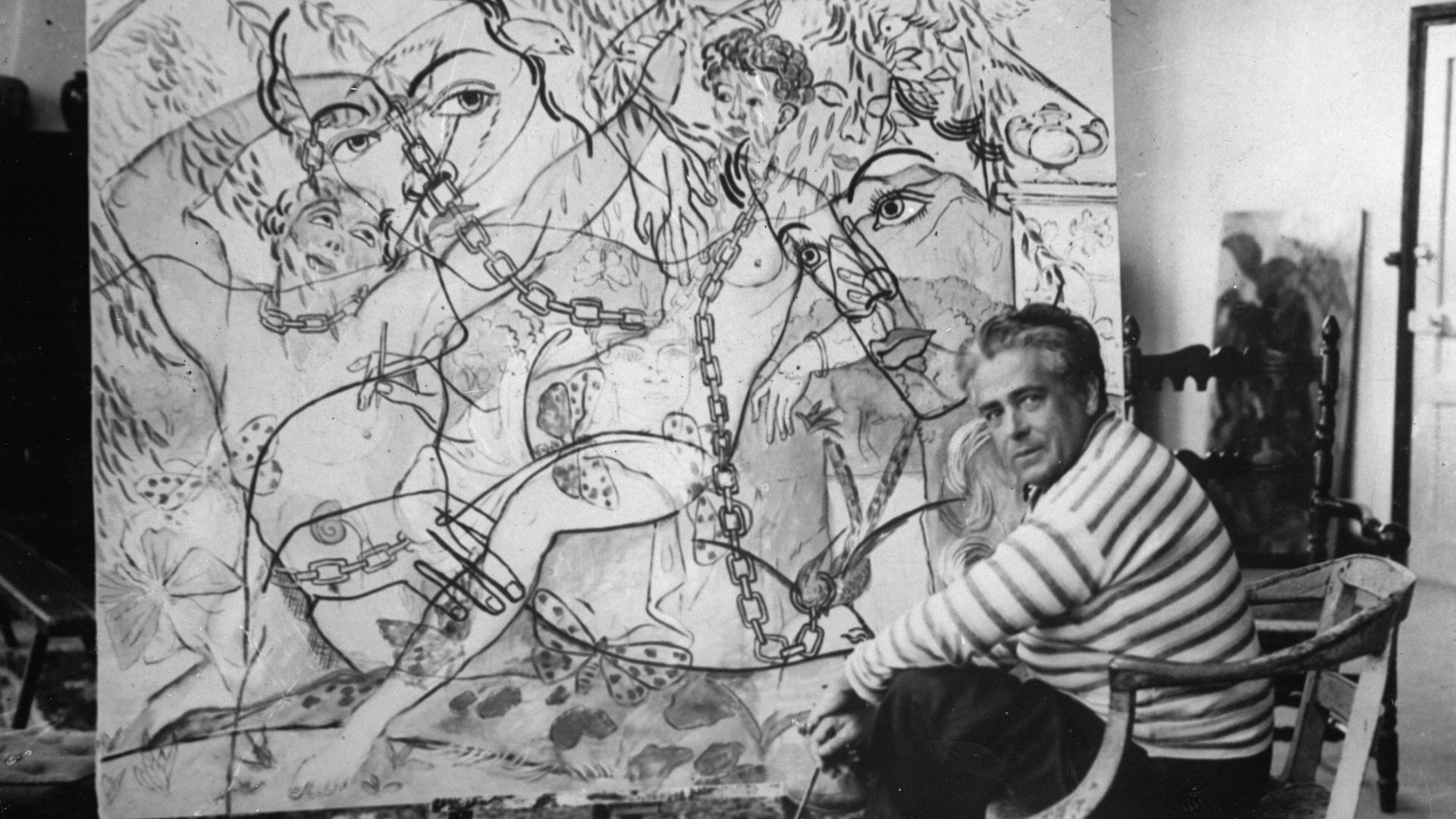

But while Picabia’s dubious talents have always divided the critics, the semi-abstract works that form his late period have, with the exception of a 2016 retrospective at New York’s MoMA, been mostly ignored. Mysterious, and difficult to fathom – it seems that no one is quite sure whether or not they are to be taken seriously. Now, the paintings from his last decade are the sole focus of an exhibition at Hauser & Wirth’s Paris headquarters, moving to New York later this spring.

Often dark, even brutish, the 45 paintings in this exhibition make an abrupt contrast with the refined elegance of the gallery, which spans two floors of an hôtel particulier (a converted grand townhouse) in the incredibly flash 8eme, just off the Champs-Élysées. Curated by Beverley Calté and Arnauld Pierre in collaboration with the Comité Picabia, the organisation set up as custodian of the artist’s reputation and legacy, the exhibition brings together works from 20 different collections in France, Switzerland, Germany, Italy and the United States and 15 private collections.

The exhibition spans the years following Picabia’s return to Paris in 1945, to his death in 1953, a period that though often characterised as abstract, rarely breaks free from the observed world. The Points series, featuring painted dots might be abstract, though The Sky, 1949 inevitably evokes the stars.

Weird as it is, Niagara, c.1947, quite easily resolves into something recognisable. It could be a mask, or prehistoric stone sculpture just dug up, but its schematised features – so blank and yet so face-like – though almost abstract, in the end are emphatically not.

Out in the topsy-turvy postwar world, in which New York, not Paris, had the scene, Abstract Expressionism was the order of the day, pioneered by swashbuckling iconoclasts Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, and Willem de Kooning. That Paris was no longer the centre of the art world represented a switch in fortunes so unconscionable that it has at points been blamed on the cold war machinations of the CIA, (a theory that sounds wackier than it is). In any case, that shift in focus disadvantaged Picabia’s work, writes Calté, arguing that “acknowledgement of its vital importance was eclipsed by the emergence of Abstract Expressionism in the late 1940s.”

It seems more likely that the world had simply grown tired of Picabia by the time he returned to Paris from his wartime retreat on the Côte d’Azur. People who mattered hadn’t yet forgotten his nudes, which in their vulgar idealism send up the conservative, classicising tendency that had become prominent in the art of the interwar years.

If that were all, they would simply be horrible paintings: but made in the early 1940s, by an artist who after the war would be accused albeit in somewhat vague terms of collaboration, these crudely perfect specimens of European womanhood are uncomfortable to look at now, and weren’t much appreciated at the time.

So it was that the awful nudes and the rumours about his wartime conduct clung inconveniently to Picabia as he returned to Paris, where abstraction was the thing of the moment. Calté claims that Picabia “obstinately followed his own path, a characteristic of his provocative individualism and indifference towards trends of the moment”. But these late pieces look more like someone doing exactly what’s required to get themselves back into favour, this time as a key figure in the Art Informel, a rather loose, but crucially European term for abstraction.

Seen as at some level a response to Abstract Expressionism, canvases like Niagara, and the gloriously textured dot painting Silence, 1949, seem more in tune with the moment than a reaction against it. Like Pollock, Picabia’s late paintings are centred on paint as material, with paint providing both means and subject matter. It’s a characteristic shared much more widely among postwar artists – think of the archaeological depths of Frank Auerbach’s paint, and Lucian Freud, who said: “I want the paint to work as flesh does.”

Starting from scratch, or Eternal Beginning as the show’s title puts it, is what Picabia did best. But after the war, it was the common quest, sought for by Picabia and many other artists in the supposedly “primitive” forms of prehistoric and non-western art. The same sentiment is there in Picabia’s dot paintings too, which with their often joyous colours, are less a denuding or denial of painting, and more as a return to the purity of its basic lexicon.

Taking Picabia seriously feels like the prelude to an embarrassing “Gotcha!”, and yet a small number of what he called “pocket paintings” all dating from 1949, are almost disarmingly sincere. Like the sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Picabia made these little works of art to carry in his pocket, a gesture that suggests a surprising sensitivity of disposition.

Things had changed for Picabia by 1949. A burglary made him truly poor for the first time in his life, and he was in the grip of a devastating, paralysing illness. It could just be possible that by the end of his life, Picabia had become a real artist.