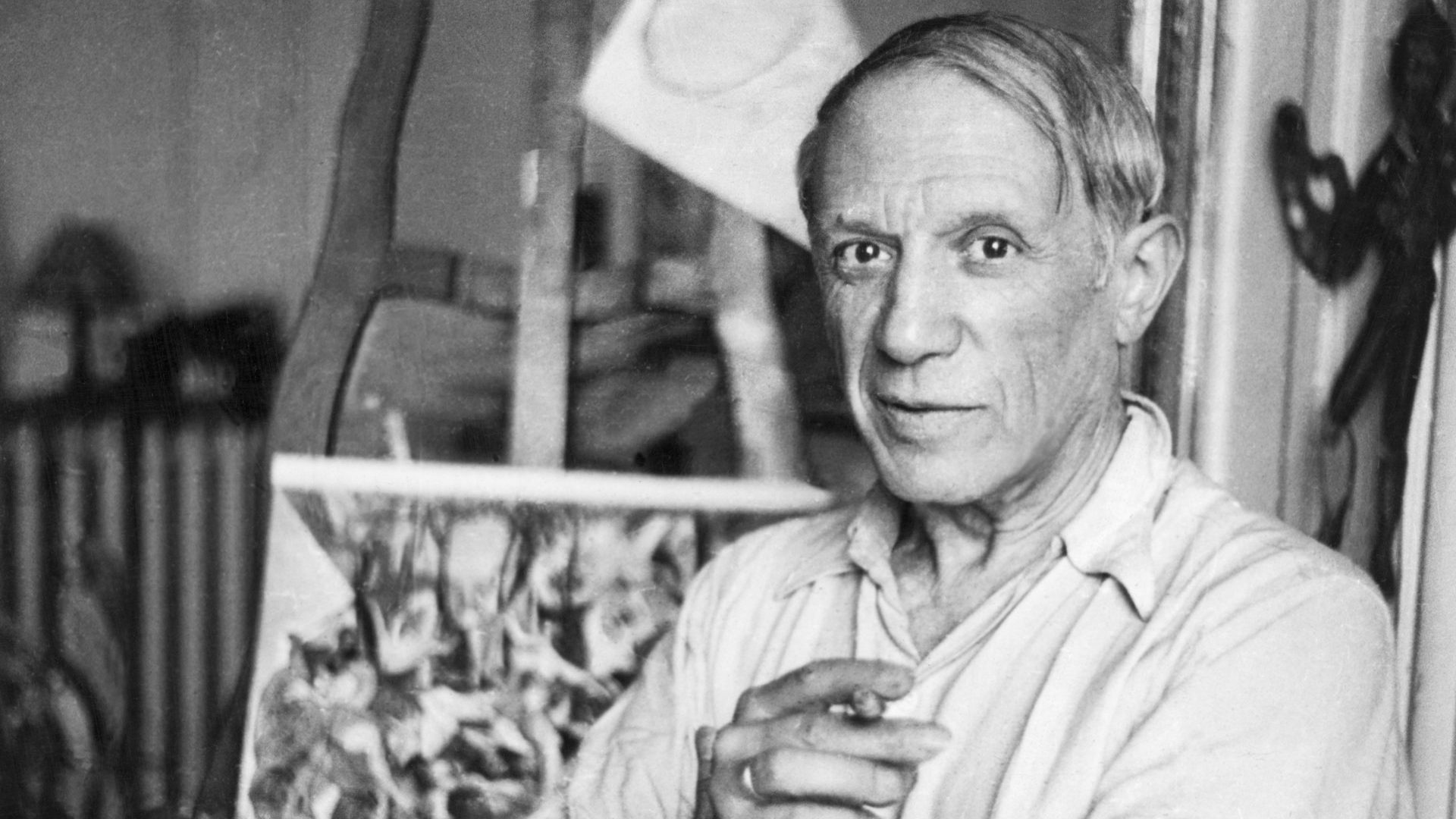

Forget winning the lottery – why not pin your hopes on turning up a lost Picasso instead? With the summer months averaging a Picasso discovery a month, and more than 1,000 works known to be missing, the work of the most famous artist of all seems to be oddly ubiquitous.

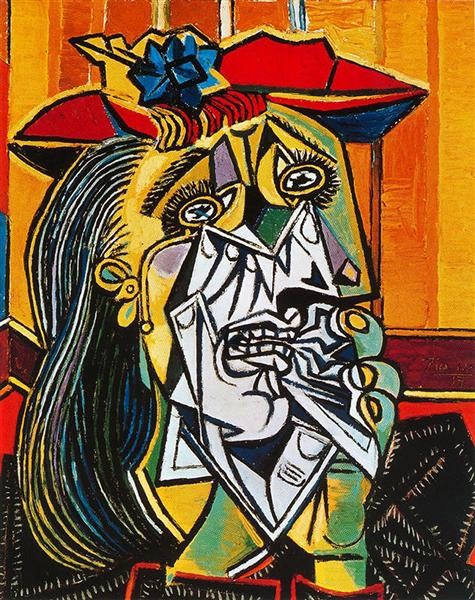

But only one among the recent spate of finds has been identified as the real thing – a smuggled drawing masquerading as a worthless copy, seized at Ibiza airport in July. Another work, a painting apparently by Picasso, was recovered from an Iraqi drugs gang in August, but the full details are yet to emerge. In May, a film crew visited the home of Imelda Marcos, widow of the former dictator of the Philippines, Ferdinand Marcos, and mother of the newly installed president, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jnr. Footage revealed Picasso’s painting Femme Couchée VI hanging on her wall.

Bizarrely, the painting appears on a list of works reportedly seized by the Philippines government in 2014, and there’s still no clear understanding of whether the painting on her wall is the real thing. One month later, in France, the artist’s granddaughter, Diana Widmaier Picasso, unearthed a stash of his sketches and origami birds made for his eldest daughter, Maya, Diana’s mother.

Over the years, there has been a steady stream of rediscovered and recovered Picassos, some of which have turned out to be the genuine article. Last year, Greek police recovered Picasso’s Woman’s Head, 1939, which had been stolen along with a Mondrian during a museum heist in 2012. In 2010, a remarkable trove of 271 paintings, drawings and prints came to light in Paris, including a painting from Picasso’s famous blue period, as well as drawings, prints and more paintings – all believed to be genuine – dating from 1900 to 1932.

A wealthy celebrity in his own lifetime, today a Picasso auction is a hot ticket event. Last year, Sotheby’s live-streamed the sale of 11 works by Picasso from the Bellagio casino in Las Vegas.

His position among the ranks of the world’s most bankable artists – along with Vincent Van Gogh and Andy Warhol – remains unassailable, and his Femme Nue Couchée, 1932, made $67.5m (£59.3m at the time) at auction in May. His most expensive painting, Les Femmes d’Alger (Version 0), 1955, was bought for an enormous $179.4m in 2015, probably by Qatar’s ruling Al Thani family.

With a record like this, it’s hardly surprising that Picasso is highly sought after, in both the legitimate and the black market.

“There’s more fake Picassos than real Picassos, and there’s a lot of real Picassos,” Donna Yates, associate professor of criminal law and criminology at Maastricht University, told France 24 in July this year.

The difficulty lies in distinguishing one from the other, a task made all the more complicated by the French system for authenticating art, which hands authority to the artist’s heirs. When Picasso died, he left no will, and his considerable estate took six years to settle between seven heirs. Prior to 2012, legally binding authentication required two of Picasso’s heirs to agree on the authenticity of an object – and agreement was not always forthcoming. The paralysing effects of the family’s internal battles were finally addressed a decade ago, when Picasso’s son, Claude, was made the sole authenticator of his father’s works.

The problem was addressed, but not resolved: as the head of the Picasso Administration, Claude Picasso receives on average 900 authentication applications each year, which are handled along with the licensing of reproductions and merchandise, as well as controversial marketing decisions such as the use of the artist’s name and signature by Citroën, the French car manufacturer. The authentication process is notoriously slow, which, combined with continued friction between the heirs and the potential for differences of opinion with other art world experts, has made space for an awful lot of supposed Picassos to remain unconfirmed.

The situation is only enhanced by the sheer scale of Picasso’s output: at his death, Picasso’s estate recorded an enormous 45,000 unsold artworks, itemised by the journalist Milton Esterow, writing in Vanity Fair in 2016:

“There were 1,885 paintings, 1,228 sculptures, 7,089 drawings, 30,000 prints, 150 sketchbooks, and 3,222 ceramic works. There were vast numbers of illustrated books, copperplates, and tapestries. And then there were the two châteaux and three other homes. (Picasso lived in and worked in about 20 places from 1900 to 1973.)”

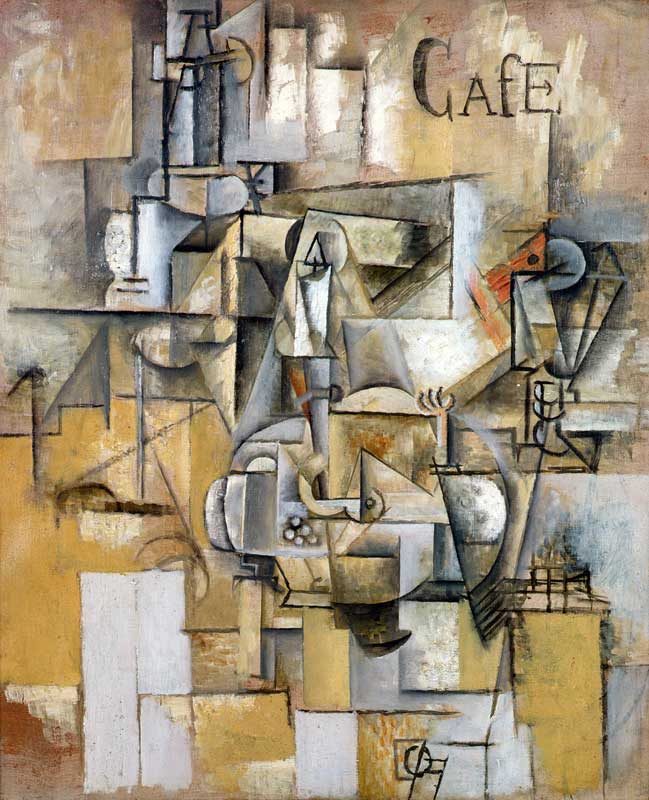

According to the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, it is estimated that Picasso produced an average of two works a day over 75 years, meaning that the total number of pieces may exceed 60,000. “The scope of techniques, styles, and themes that Picasso covered remains unimaginable and incomprehensible, all the more so since no list seems to have been made of all his works in every genre,” a state of affairs that makes it perfectly conceivable that there are works yet to be discovered. This makes Picasso an ideal target for forgers.

What is more, Picasso’s entry continues: “Throughout his very long career, he did his utmost to do what he did not previously know how to do and… eventually, it emerged that he knew how to do everything.” Picasso experimented with a huge range of styles and techniques, and his artistic curiosity, as well as his extraordinary work rate, create the ideal circumstances for the sudden discovery of a plausible, but fake, “lost work”.

The discovery of Maya’s origami collection illustrates the scope for ambiguity – for while there is no suggestion that this particular find is anything other than bona fide, the authenticity of items made for private enjoyment rely heavily on the circumstances of their discovery and the word of the finder.

The rock-solid value of a genuine Picasso has made the artist’s works attractive targets for organised crime syndicates, which expanded their activities into art theft in the 1960s, having taken note of the increasingly eye-watering prices being paid at auction. The last recorded figures released by the Art Loss Register place Picasso as the world’s most stolen artist, with 1,147 missing works.

The most recent examples of recovered Picassos illustrate the continued value of art to criminal gangs: while they may attempt to hold the owner or insurance company to ransom, they are more likely to use the art as relatively portable collateral that can be used as security in deals involving arms and drugs.

The most dramatic, and often violent, art heists stick in the public memory, such as the theft in 1976 of 119 Picassos from the Papal Palace at Avignon, described by Noah Charney, the author of The Museum of Lost Art, as “the single largest peacetime art theft in history”.

The report in the New York Times on February 2 1976 continued: “The robbery last night was one in a series of art thefts. This afternoon, a precious 14th-century Italian miniature was taken out of the Louvre here. A week ago, 125 Picasso prints valued at $500,000 vanished from a Paris art gallery.” Furthermore: Police tallies indicate that thefts of master paintings in France have risen, from 1,500 in 1970 to near a current annual rate of 5,000.”

The Avignon thieves were arrested and the paintings recovered – among them Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907, one of the most famous paintings of all time, and typically considered to represent a crucial moment in the trajectory of 20th-century art – but Charney notes that a satisfactory resolution is rare: “In as few as 1.5% of reported art thefts are objects recovered and criminals brought to trial.”

Of the missing Picassos, one that is feared lost for ever is Le Pigeon aux Petits Pois, an example of analytical cubism dating from 1911, stolen from the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris on May 20 2010. Though the thief was later arrested, he claimed to have thrown the painting into a skip outside the museum, information received too late to act on.

Compared to smash and grab robberies, art smuggling may seem relatively innocuous, but it often has connections to more nefarious activities. The Picasso drawing intercepted in Ibiza recently may have been smuggled in order to avoid export restrictions, or taxes: indeed, the freeports with which the Tory government is so enamoured have become invaluable tools for plutocrats, who habitually use them to store art tax-free.

Portable, hugely valuable, and only identifiable by an expert, art has become an increasingly convenient way for criminals to move large sums of money undetected, slipped inside a case or, even better, stowed on a private yacht.

“Hemingway’s Picasso”, a podcast series that began in September 2021, tells the story of a supposed Picasso ceramic used as payment for a drug deal by none other than Pablo Escobar, the notorious Colombian drug lord.

The ceramic, which has not been authenticated, was said to have been given to Hemingway by Picasso himself, eventually finding its way into the hands of Steve Kough, a drug smuggler who died in 2018, who claimed it was given to him by Escobar in 1989.

Whether a genuine Picasso or not, the ceramic may still prove to be a collectable piece because of the story attached to it. Meanwhile, the art market continues to thrive in an increasingly uncertain world, in which a Picasso is as safe as houses – so long as it really is a Picasso.

Florence Hallett is a freelance art writer and critic