Growing up in the comfortable Bristol suburb of Clifton, her mother intent on turning her out as a “polished corner”, Marjorie Watson-Williams might reasonably have felt that her artistic ambitions were unnecessarily hampered. So it was that in 1926 she became Paule Vézelay – French-sounding, and ambiguously masculine, it was a name to mark the start of a new life in Paris, where in the decade or so before the second world war she would find her place at the heart of the European avant-garde.

Vézelay was European to her bones, and long before she set foot in Paris, she sought out echoes of the city’s nightlife in local haunts such as the Bristol Hippodrome which had opened in 1912. Her imagination was no doubt full of Degas and Manet, and Sickert too when she painted her c.1918-1919 watercolour of the theatre’s interior, her choice of subject a nod to what was by now the thriving, but still distinctly European modernist genre of everyday urban life.

Bristol Hippodrome is one of the earliest works in Paule Vézelay: Living Lines, the first major exhibition for more than 40 years to be dedicated to the artist. It features more than 60 works from private and public collections, including letters, textiles, paintings, drawings and sculptures, and takes place at the Royal West of England Academy, Bristol (RWA), formerly the premises of the Bristol School of Art where Vézelay was a student between 1909 and 1912.

She briefly attended the Slade School of Art and then the London School of Art after moving to the capital in 1912, but she was itching to leave. “English art bored her to tears”, says curator Simon Grant, and after a few years of travelling and exhibiting in Europe, including with Margaret Morris’s avant-garde dance school in the south of France, she settled in Paris.

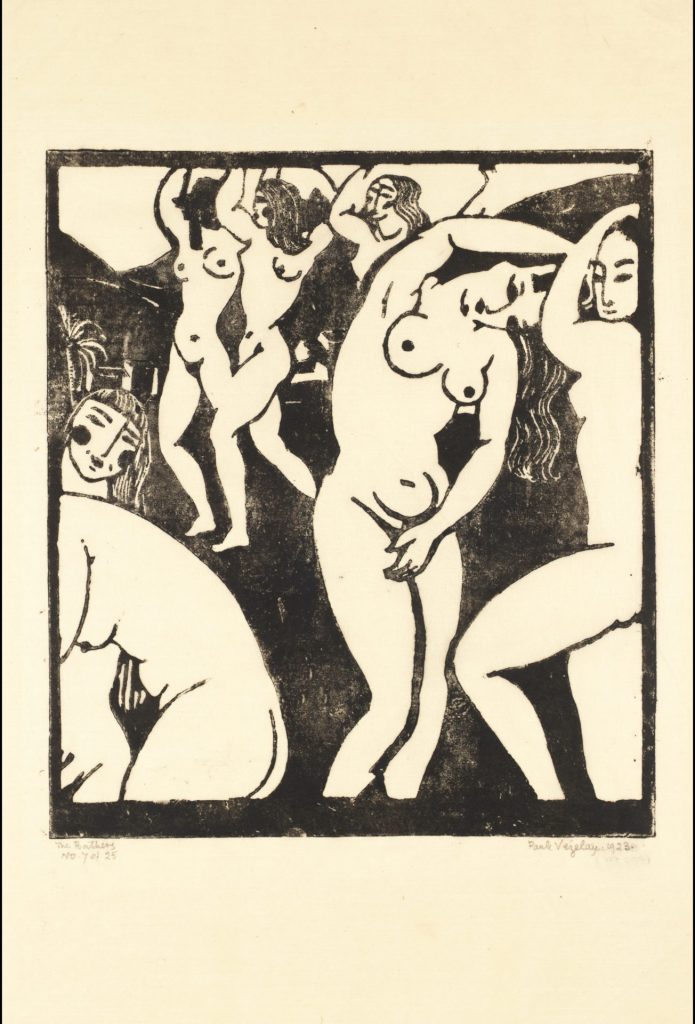

It’s here that the exhibition picks up her story, just as her restless figures of dancers or circus performers, often made in woodcut, etching, or linocut rather than paint, gave way to a more abstract, yet still descriptive, characteristically animated style.

Her first abstract drawing (now lost) was dated 1928, and formed the grounds for her claim late in life that, “I am the first English abstract artist (not the first female artist) to have made an international reputation”. Though this is not true (Wyndham Lewis and David Bomberg were earlier), Simon Grant points out that her experiment still predated those by such famous pioneers as Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore and Ben Nicholson.

A well-conceived hang presents Vézelay’s transition from figuration to abstraction as a natural progression rather than a seismic shift, emphasising the continuity of thought between the sinuous lines of Two Women, 1927, for example, and her 1929 painting The Sunbathers. In the painting, the female figure is distilled and deconstructed into calligraphic lines and suggestive forms – a progression rather than a wholesale change of approach.

Artist women are so often minimised as “influenced by” or “derivative of” their male counterparts, that it is vitally important to establish the inner logic that drove Vézelay’s art, not least because her shift to abstraction gathered momentum at around the same time that she began a four-year relationship with the sometime surrealist André Masson, whose own explorations of abstraction were underway when they met in 1929.

Young, highly motivated and still new in Paris, where she put herself at the centre of artistic life, she was naturally receptive to influences, especially the explorations of line and form in space of Alexander Calder, Marlow Moss, Joan Miró and later, Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Jean Arp. Masson’s surrealist practice of automatic writing seems to have unlocked Vézelay’s own ideas about the “life” of the line, which she saw, as some novelists do about their characters, as not fully under her command.

Masson’s impact on Vézelay was painfully complex, as she made clear in 1954, in a frank letter to the gallerist Oliver Brown. “He did not tell me then that he was a 50% war wounded nervous case and had been in a mental home at the end of the 1914 war,” she wrote, explaining that they had decided to get married.

“Before long, I became perplexed and worried by Masson’s inexplicable moods; he seemed like two people in one, the man I loved – interesting, charming, happy and a gifted artist; the other a cruel, violent and cunning person without loyalty or self-control.”

In fact, like many women of her age, Vézelay had experience of men traumatised by the first world war; her two younger brothers were both devastated by it, the youngest, Guthrie, just 17 when he suffered severe shell shock after being blown up. For a while, she coped with Masson’s violent and unpredictable temper. She went fishing for trout, says Grant: “It was either that or playing squash.”

Fishing was a habit formed in childhood, when she would accompany her father. In idle moments, he would get out a sketchbook, and so the association between fishing, drawing, nature and contentment were established in her mind very early on.

“You get a sense that her obsession with shadows and silhouettes, which is a really strong theme that runs through the whole exhibition, comes from very personal responses to experiences like seeing a fish moving in a stream,” says Grant.

For the most part, she was reluctant to make such literal connections herself, but they are undoubtedly there, and not just in the organic, and often rather joyful forms that appear in her work after 1932, and later works such as Paysage, 1946, a fairly straightforward expression of joy in nature.

Wanting to “free the line” from the confines of two dimensions, in the mid-1930s, Vézelay began working in more geometric terms, stretching threads across a board, as in Lines in Space, No 3, 1936. Its connection with nature can be understood by looking back to a slightly earlier collage, made from leaves and fishing flies, with fishing line stretched taut, to create intersecting lines.

Here, too, are the beginnings of her late, and very successful career as a textile designer, notably for Heal’s between 1954 and 1967, following her return to England at the outbreak of the second world war. The designs often originated as paper cutouts, which are anticipated in the self-contained, isolated forms seen first in her collages and later in paintings.

Despite commercial success, the art establishment paid her little attention until 1983, the year before she died, when the Tate staged a retrospective. At the same time she was interviewed by Germaine Greer for the BBC, a wonderful film intermittently to be found in the darker reaches of iPlayer.

Shot at her home in Barnes, south-west London, canvas upon canvas is stacked against walls. “She came to think of her works as her own children and became reluctant to part with them at any price,” writes her niece in the accompanying catalogue. Consequently, it is only now that Paule Vézelay’s reputation is being properly established: despite everything, in the end she was, as her mother would have said, a “polished corner” – too genteel to engage with the grubby business of selling paintings.

Paule Vézelay: Living Lines is at the Royal West of England Academy, Bristol, until April 27, 2025