Hans Coper’s celebrated pots are typical of the postwar British “look”, their appearance of archaeological antiquity combining with clean-lined minimalism to achieve a monumentality uniquely mid-20th century.

The potter’s traumatic life story, and the trajectory of his career are similarly representative of the experiences and circumstances that shaped Britain’s recovery in the 1950s and 1960s. Having fled Germany for England in 1939, Coper (1920- 1981) spent the early years of the war interned as an “enemy alien” before joining the Pioneer Corps in 1941, from which he was discharged in 1943 after suffering a mental breakdown. It was in London after the war that he met fellow émigré Lucie Rie (1902-1995), some years older and already a potter of experience and reputation.

They were among countless refugees from Nazi-occupied Europe who contributed to the rebuilding of British society and cultural life after the war, and Coper’s career was nurtured by state-sponsored arts commissioning that, along with the NHS and the welfare state, marked a new and radically progressive approach to government.

For this reason, The Arc, in Winchester makes the ideal setting for Hans Coper: Resurface, a small and tightly curated exhibition with three murals – the only three Coper ever made – each one a public commission, at its heart. A gallery space is just one element of this thriving cultural centre, which hosts performances, classes, and community services, as well as a well-used library and café.

It’s a beacon of municipal pride, but it’s also symptomatic of the erosion of state provision – The Arc is administered not by the local council but by Hampshire Cultural Trust, an independent charity established in 2014 to take over the running of cultural concerns previously under the care of Hampshire County Council and Winchester City Council.

A different atmosphere prevailed in the late 1950s and 1960s, when Hans Coper was commissioned to make the three murals at the heart of this exhibition, seen together here for the first, and quite probably the only time. Together, the Swinton School Mural, the Powell Duffryn Mural and the Royal Army Pay Corps Mural exemplify the “art for all” ethos of those years, embodied by the Arts Council, founded in 1946 to distribute public funds for the arts.

For architects and town planners, the provision of new housing, schools, shopping precincts and other municipal spaces was a chance to realise a utopia, and in new towns, like Harlow, Essex, public sculpture was integral to this vision.

From the late 1950s, a number of architects began to invite collaborations with artists, notably at Coventry Cathedral, which like the 1951 Festival of Britain showcased British creative talent with an array of contributions from across the arts. It was for Coventry that Coper produced his most famous public work, six seven-foot-tall candlesticks, small maquettes for which are on display in this exhibition.

Far more common were commissions for schools and other public buildings, where murals in particular, often made out of novel materials such as fibreglass, cement, and in Coper’s case, ceramic, enjoyed a period of booming popularity. According to a 2016 report by Historic England: “The demand for mural works was so great that an average of more than one substantial work per fortnight was installed in England during the 1950s and 1960s.”

Coper’s involvement with architectural projects began in 1959, when he accepted an invitation from the educationalist and founder of the Cambridgeshire Village Colleges, Henry Morris, to take up a residency at the Digswell Arts Trust in Hertfordshire. The Trust was founded by Morris in 1957 as a complex of studios and accommodation for artists engaged in civic projects, and over the years many distinguished figures spent time there, notably the painter Michael Andrews, the potter Elizabeth Fritsch, the sculptor Ralph Brown, and the weaver Peter Collingwood.

For Coper, the move marked a turning point in his career: when he became Rie’s studio assistant in 1946 he had no prior experience, though Rie would never accept that he had been her student or apprentice, insisting that, “He educated me, he knew much more than I did”. In 1951 he exhibited alongside her at the Festival of Britain, and when in 1961 he installed the Swinton School Mural, it was Rie who helped him.

That commission, along with the other two murals were a product of the Digswell residency, likewise the commission for the Coventry Cathedral candlesticks. But he was also engaged on many more prosaic projects, designing bricks, and cladding tiles for the prefabricated buildings developed to solve the housing crisis, represented here by a plaster mould for manufacturing acoustic tiles.

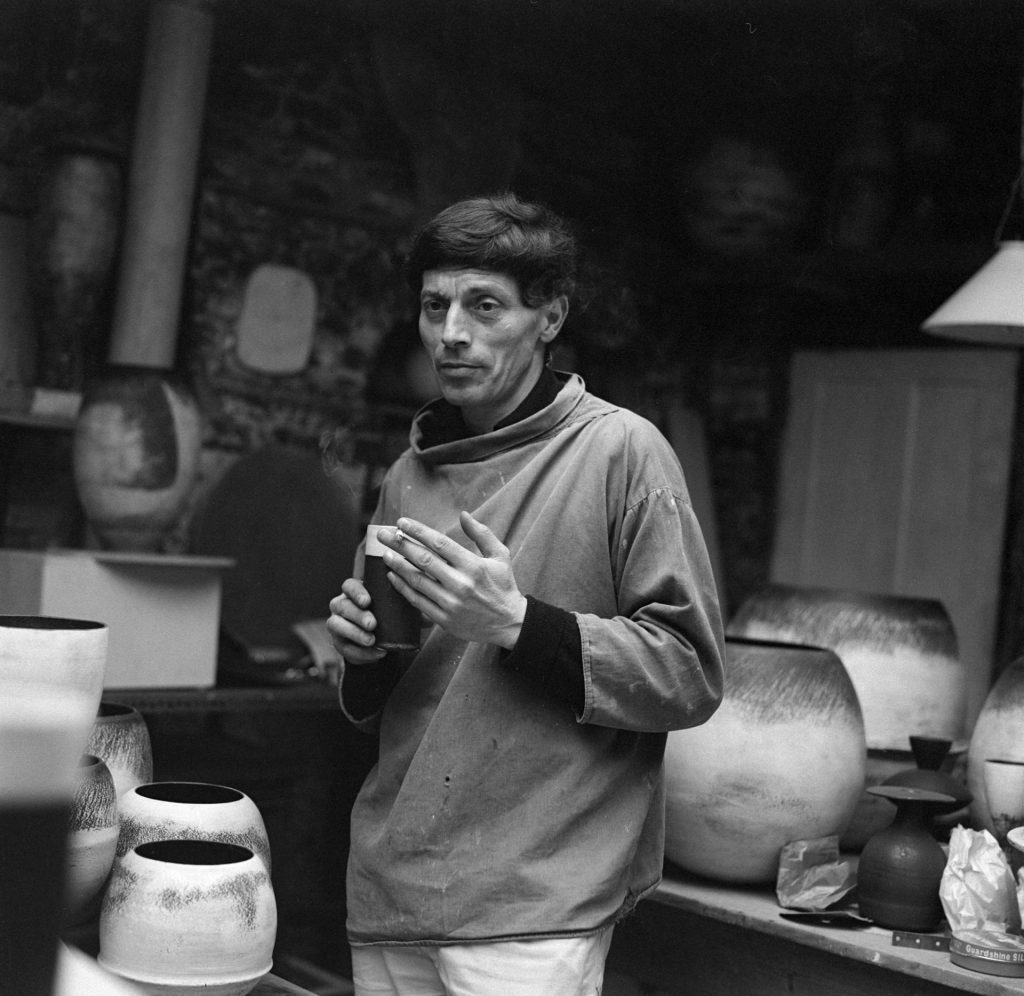

Coper continued making pots all along, and the 20 or so examples on show here trace his development of increasingly sculptural designs, made always using the same industrial white clay, and finished with a marvellously complex patina. Though Rie and Coper are very often discussed as a pair, and there are similarities between their work, Rie always worked to a domestic sensibility, while Coper remained true to his early aspirations as a sculptor.

Still, Coper’s path was not simply the result of his happy meeting with Rie, as is made clear in his only surviving statement, written for a 1969 exhibition at the V&A in which his work appeared alongside that of his Digswell contemporary Peter Collingwood. In it, he describes a “pre-Dynastic Egyptian pot, roughly egg-shaped, the size of my hand, made thousands of years ago possibly by a slave, it had survived in more than one sense.” He concluded: “This is the only pot that had ever really fascinated me. It was not the cause of me making pots, but it gave me a glimpse of what man is.”

This sense of survival, and of a vessel, nominally utilitarian as it is, acting as a repository of accumulating sensations and experiences, is embodied in Coper’s designs, which not only appear to bear the scars of time, but evoke the hand tools of the Stone Age, in “Spade”, “Disc” and “Thistle” forms. Later in his career, the echoes of this “egg-shaped” pot seem to become louder, the eggshell-like walls of a Cycladic “Bud” Pot, c.1975, bringing a startling fragility to its robust, egg-shaped form.

There’s a striking socialising tendency to Coper’s works, deriving in part from their functional, convivial roots, and expressed in the ease with which they sit with one another in arrangements captured to splendid effect in the black and white photographs taken by Jane Coper, his wife. It’s an idea intrinsic to Coper’s works, which often consist of multiple forms brought together in a single object, and made explicit in the Tripot, c.1956, on display here, in which three vessels are fused at the rim.

It’s a remarkable exhibition that reveals as much about the spirit of social justice and shared humanity that drove the public projects of the 1950s, as it does about the enigmatic figure of Hans Coper.

Hans Coper: Resurface is at the Arc, Winchester, until March 25