Heraclitus said that you can’t step into the same river twice and that everything is in flux. Even if you step into the river only a second later, you and the river will both have changed. In that sense, there is no such thing as “the same river” or “the same person”.

Like Heraclitus, Henri Bergson believed that at a deep level, everything is flux and that words fail to capture some aspects of that. He’s the subject of a very entertaining biography, Herald of a Restless World by Emily Herring, published last week.

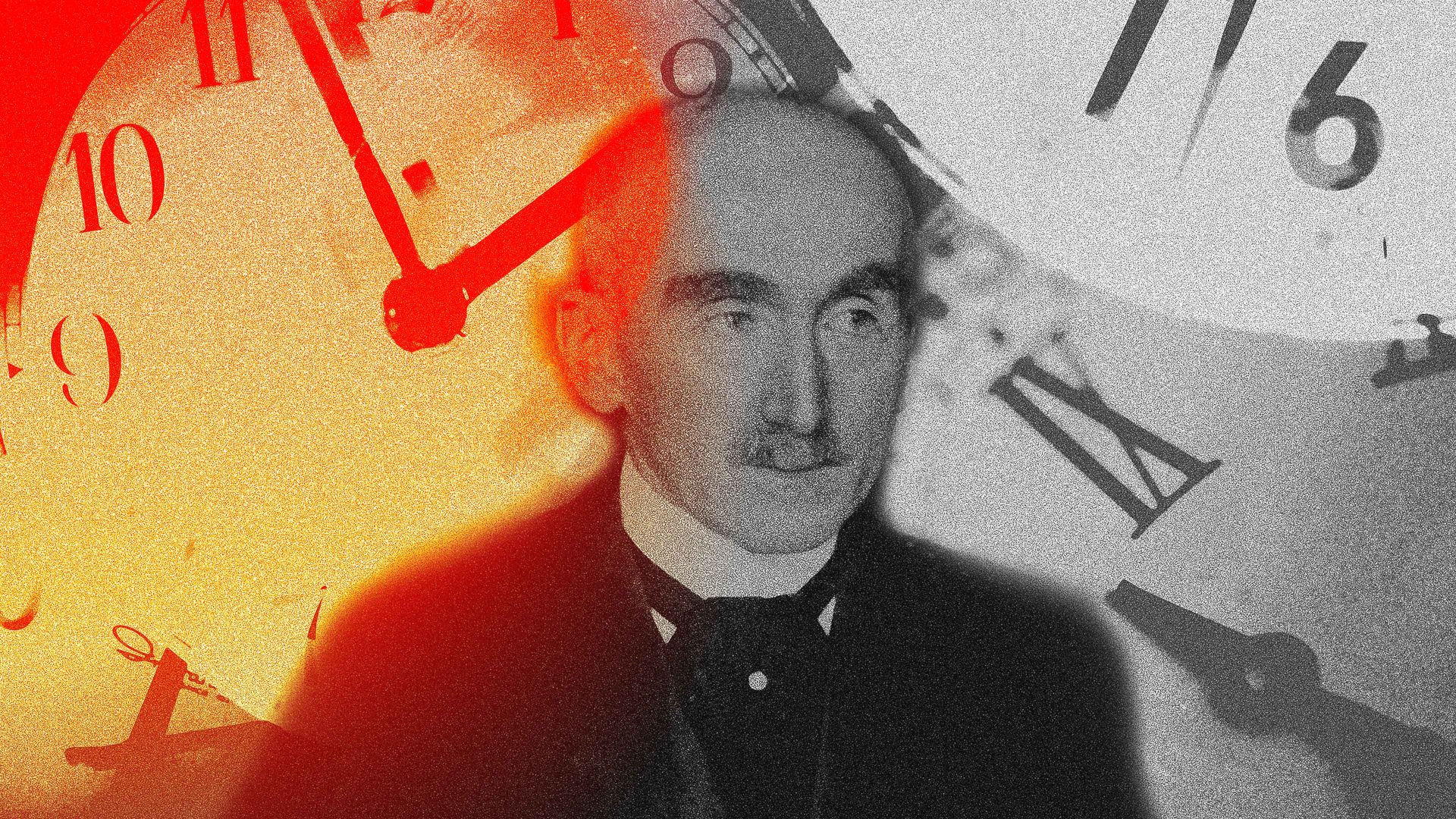

She recounts how, in the decade leading up to the first world war, Bergson became an international celebrity who counted William James among his fans. When Bergson visited Columbia University in 1913 he caused the first ever traffic jam on Broadway. His Collège de France public lectures in Paris had more than 700 people squeezing into a room designed for 375, and near riots outside. This rather timid-looking man with a large domed forehead and small moustache captivated his audiences.

Bergson was active in an era of widespread anxiety about technological change, including the new forms of travel and communication that were transforming people’s relationship with time and place. One of his central and most important ideas resonated with this anxiety. This was “durée”, literally “duration”.

Bergson claimed that the dominant view of time, which treated it as divisible into separate discrete measurable units, clock time if you like, didn’t capture what was most important about temporality. Clock time was a spatial concept: represented as divisions on a clockface, or points on a line. According to Bergson that scientific fixing of time missed out something essential, durée.

Durée is the lived experience of time, the way in which our memories are part of our experience of time, with past experience occupying an essential element in that. We don’t sense time as discrete seconds, rather we feel past and present merging together and infusing one another. The objective measurements of clock time, although important for scientific research, or running a railway schedule, don’t capture what time really is at a deeper level.

Even Bergson acknowledged that this notion of durée was not easy to grasp or communicate. When a reader wrote asking for clarification of this elusive concept, Bergson replied that part of the difficulty was that it “goes against the essence of language” and that he could only attempt to “suggest” it. What that meant in practice was that he used metaphors and analogies to try to communicate what he felt and sensed to be true about our relation to time in the hope that others would recognise what he meant.

This difficulty of explaining what time was is something St Augustine noted in Confessions:

“What then is time? If no one asks me, I know what it is. If I wish to explain it to him who asks, I do not know.”

One analogy Bergson used was with music. You can transcribe music into notes on a score, but that is not what the experience of music is like. Listening to music isn’t simply attending to successions of present notes, but rather of past notes and chords blending into the present ones and only making sense in relation to one another as we hear the melody and harmony developing. We even hear future notes implied in the present ones. Durée is like listening to music.

Many felt they knew what Bergson was getting at, or at least partly recognised what he meant. They felt they gained important insights into their relation to past and present and to how memory infuses our experience. Marcel Proust, who was best man at Bergson’s wedding (he was a relative of Bergson’s wife), may have been among these, though in an interview he tried to distance himself from the idea that In Remembrance of Things Past was just Bergsonianism with a plot.

Others who encountered Bergson’s ideas were less impressed. Bertrand Russell, perhaps envious of the French philosopher’s celebrity status, became his severest critic. “I hate his dogmatic pontifical style,” he fulminated in a letter to Ottoline Morrell. In A History of Western Philosophy Russell let rip, savaging Bergson’s style of doing philosophy, his lack of argument for his positions, the way he resorted to poetic images that could not be proved or disproved.

Herring credits Russell with having persuaded generations of anglophone readers that Bergson wasn’t philosophically meaningful. Perhaps it’s time to give Bergson another chance.