We are usually only held responsible for what we do or fail to do. If other people act immorally, then they’re responsible for that, not us. That’s why the Christian concept of Original Sin (first labelled by the great African philosopher Augustine) can be so hard to stomach. It implies that we are all tainted by Adam and Eve’s disobedience in the Garden of Eden, even though we weren’t there and didn’t bite into the apple. After their fall, we all inherited a sinful nature and there’s not a lot we can do about that except try to avoid sinning even more. To me, that doesn’t seem fair.

In some cases, though, we can and should still regret and seek to make amends for things that others have done long before we were born. Recently, the Guardian newspaper has been examining the degree to which it has benefited from past links with transatlantic slavery.

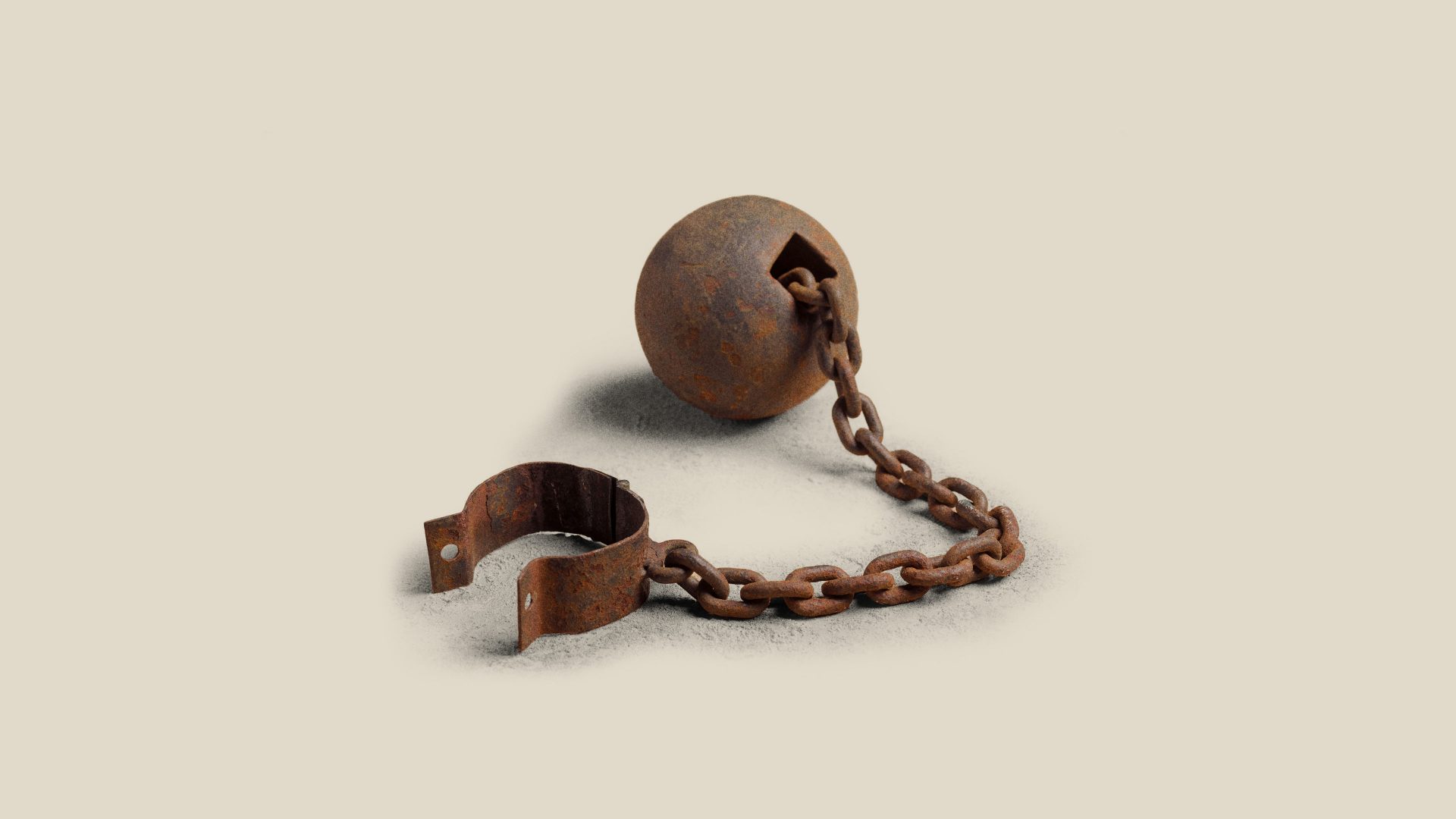

It turns out that the founding editor, John Edward Taylor, gained much of his wealth from the Manchester cotton industry, an industry that relied on enslaved people who had been captured, shipped across the Atlantic and forced to work on plantations in the American South in brutal and inhumane conditions where they were treated as chattels rather than human beings. He also received financial support from speculators who had made huge amounts of money trading sugar in Jamaica, and the sugar industry at that time also relied heavily on the labour of enslaved Africans.

As the historian Prof David Olusoga put it, “Within the financial DNA of the Guardian are the stolen labour and lives of enslaved people in the United States, Jamaica and Brazil.”

The Guardian’s owner has made both a public apology and a commitment to a programme of restorative justice, which will be directed towards descendants of enslaved people brought from central and west Africa to southern US states. The newspaper also intends to fund programmes for black journalists and to help raise awareness about transatlantic slavery and its legacies, emphasising the degree to which the successes of the British Industrial Revolution were fuelled by this abhorrent treatment of enslaved Africans.

The Guardian isn’t alone in facing up to its past. The Church of England is starting to address its shameful history, too. In the 18th century it invested in the South Sea Company, well aware that its profits came from the trade in enslaved Africans. The church, which became rich through this involvement, has recently ringfenced £100m to research and make some amends for this.

Contrast that with the heel-dragging British monarchy, which historically has increased its wealth from involvement with slavery. So far there have been some words of regret from King Charles and an expressed willingness to investigate the web of links between his ancestors and slavery. The chances of reparations following soon, however, are slim from the family that is still holding on to a range of plundered gemstones from India and is intensely secretive about its own immense wealth and where it came from.

The Guardian, the Church of England and the present-day royal family – none of these have been directly implicated in slavery themselves, of course. They are nevertheless still tainted by a modern form of Original Sin. Another way of putting all this is that some of the money these groups have invested today is dirty money. Very dirty indeed.

History can’t be undone. But when you discover you have something that was acquired by immoral means and really should belong to someone else, you have a moral duty to try to give it back to its rightful owners or to their successors, or at least not to pretend that nothing happened. The right course of action in this context is to attempt some kind of reparation to make amends to descendants of the people who were so wronged, while realising that this gesture couldn’t possibly match the scale of harm inflicted on the victims and the generations that followed them.

An apology will be just words, and even offensive if not backed up with attempts to go further. Sincerity requires more than a statement of regret that something happened long ago, particularly when those apologising have the means to help people alive today who have been badly affected by what was done to their ancestors. The Guardian and the Church of England shouldn’t be the only ones to see this.

Let’s hope they won’t be. Over to you, Charles.