There is a wonderful video of the philosopher and novelist Umberto Eco, famous for The Name of the Rose, a book in which the library in a medieval monastery is a central character. He is in his own house, and he goes to search for a particular volume. The camera follows Eco at a brisk pace as he walks past shelf after shelf of books in the maze that was his personal library, before retrieving the book he is looking for almost a minute after the shot begins. He had over 30,000 books at home, and divided visitors into those who asked him how many of them he had read and those few who recognised that this collection was his research tool.

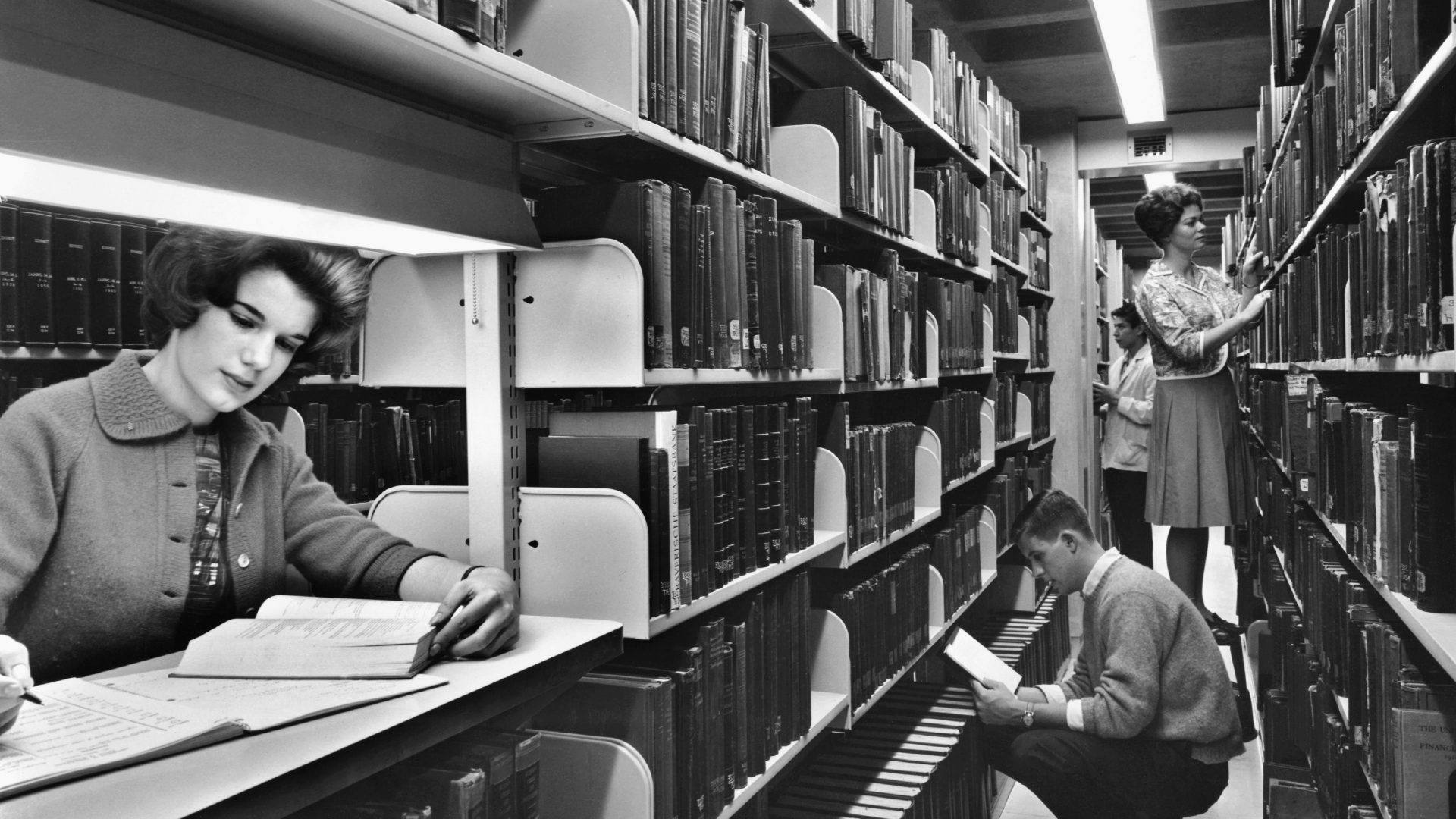

Eco spoke of libraries as humanity’s common memory, both symbolically and in reality. His own books were acquired after his death by the Italian government and shared between libraries in Milan and Bologna, the cities in which he worked. Yet for the most part libraries, whether personal, university-based, or public are dwindling in the age of the internet. We seem to have all the information we need in digital form, readily accessible on a smartphone. Why do we need these temples to paper-based technology any more? Couldn’t we get the same information from Google?

This question is becoming particularly acute as universities tighten their belts and councils in the UK come under intense pressure to reduce costs. Inevitably both research and community libraries will suffer, despite university libraries being at the centre of academic study, discovery and communication, and the statutory requirement for councils to provide and maintain community libraries. The loss in both areas will be great. Serious damage has already been done. Worse is to come.

For great research libraries, like the Bodleian Library in Oxford, the British Library in London and the Cambridge University library, the role of preserving and providing access to manuscripts, books and papers accumulated over centuries is key. But these are not simply storehouses for archives: they are active evolving centres for research using new technology to curate and make available irreplaceable relics alongside contemporary contributions.

In his classic The Five Laws of Library Science published in 1931, SR Ranganathan produced this set of principles:

- 1) Books are for use.

- 2) Every person his or her book.

- 3) Every book its reader.

- 4) Save the time of the reader.

- 5) A library is a growing organism.

We are well beyond thinking of libraries simply as repositories of paper books, but these principles still hold, particularly the last one. The Bodleian librarian Richard Ovenden has spoken of libraries as organised bodies of knowledge, but how we organise knowledge and what it consists of is a dynamic process, not a static one. Development needs adequate funding, and a team of well-trained imaginative professionals. A research library can’t be replaced by a series of subscriptions to online journals, even if some cost-cutting university managers naively think it could be.

Nassim Taleb in The Black Swan suggested that we should see the value of Eco’s books as an anti-library. A library, in his view, should be full of unread books that stare menacingly at us reminding us of what we don’t know. That seems to go against Ranganathan’s first law, but in fact these books are potential resources and valuable even when they aren’t all consulted. Eco’s library to be effective had to contain numerous books that he would never read. Unread books have a use. The same is true for our research libraries. They should be full of unused resources. Unread books shouldn’t be sold off. A library needs to contain more than its readers could ever read.

Community libraries are different from these. They serve multiple purposes. They are, among other things, a democratic resource providing free access to information for all, including guided access to the internet for those who might otherwise be excluded. They have huge symbolic importance too, representing a commitment to the common good, and are staffed by experts who can help people from a wide range of backgrounds find what they are looking for, as well as services that they didn’t realise they might be able to use. Increasingly they are becoming refuges for the cold, vulnerable and homeless.

Unlike research libraries, their collections needn’t be huge, but they do need funding and imagination to keep them vibrant places of discovery, hope and opportunity. We can’t afford to let them perish.