Edmund Burke, the Anglo-Irish philosopher-politician often described as the father of conservatism, died in Beaconsfield on July 9, 1797. The modern UK Conservative Party died on July 4, 2024. I can’t say I’m sad about the latter.

But does it really make sense to talk about Burke as the father of conservatism? Jesse Norman, one of relatively few Tory MPs re-elected to parliament last week, and author of a biography of Burke, describes him as “in many ways the first conservative”. Niall Ferguson has taken a similar line, as has David Starkey.

Other historians dispute their claim. Richard Bourke, for example, points out how misleading it is to see his almost namesake through that lens. Burke was on the side of the American colonies resisting taxation, even to the point of endorsing violent revolt. In later life, he also championed the cause of reform and even rebellion in both India and Ireland – hardly what we think of as conservative positions on the empire.

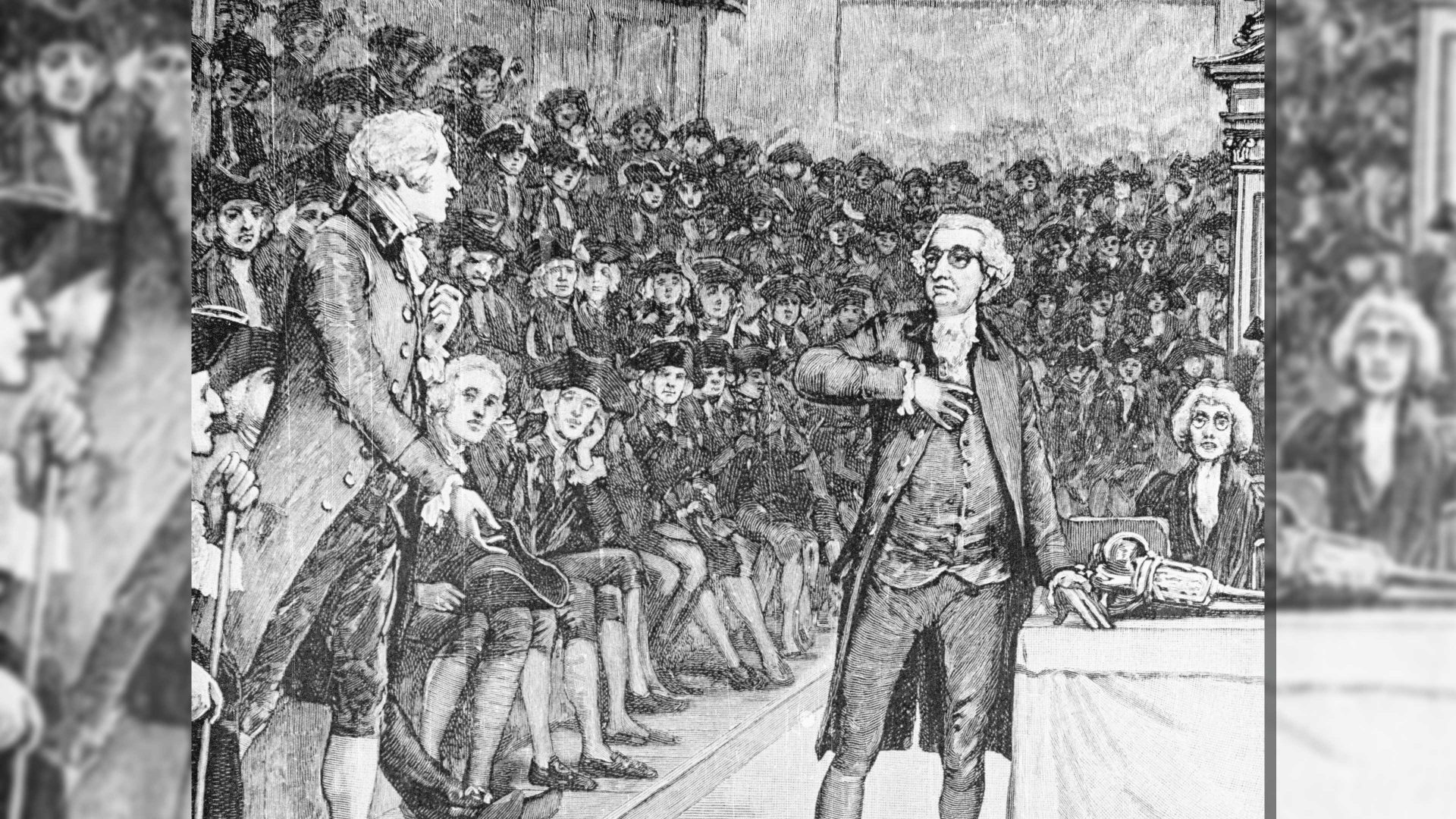

The main reason so many conservative thinkers want to claim Burke as their ancestor, and have done for over 150 years, is his opposition to the early stages of the French revolution, crystallised in his book Reflections on the Revolution in France, published in 1790. There he expressed his fear that redistribution of land, together with greater equality, would result in disaster, turmoil, and long-lasting civil unrest. The revolution didn’t just threaten property, the aristocracy and the monarchy, but religion and sound government, too, all in the name of abstract ideas.

Burke was on the side of stability, tradition, reverence for authority and maintenance of the hierarchical social order. In place of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s romantic notions of freedom, he wanted ordered liberty, the freedom of a well functioning society built on the wisdom of ages, rather than theorised into existence.

Rousseau had opened The Social Contract with the claim that “Man is born free but everywhere is in chains”. Burke rejected that universalistic vision as simplistic and dangerous. He feared that for all its focus on liberty, equality and fraternity, the revolution would end in tyranny.

He was a philosopher who was suspicious of giving too much weight to philosophy in politics. Reason should not necessarily overthrow local tradition. You can’t simply remodel societies wholesale.

Burke’s book was an instant bestseller, but Thomas Paine’s response, The Rights of Man, sold even more. This worried the authorities.

Paine, in contrast with Burke, had no time for hereditary monarchy and the aristocracy. He was an enthusiastic supporter of the revolution and of the right of the people to overthrow their government. He ended up fleeing England for France to avoid prosecution for radical ideas that some thought would incite a revolution on this side of the Channel.

Before entering politics, Burke had wanted to pursue a literary career. That was his initial reason for coming to London.

In his early 20s, he had completed his influential A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. There he put forward a psychological account of how beauty tends to produce pleasure, but sublime objects, such as rugged cliffs and mountains, or a thunderstorm, move us profoundly in a different way. Their effect is linked with our capacity to feel terror and a sense of danger.

Beautiful objects tend to be small and exquisite, while sublime ones are huge and threatening, dangerous even. Those drawn last week to watch as Etna spewed ash and molten lava high into the sky will understand what he meant.

Yet it is chiefly for Reflections on the Revolution in France that Burke will be remembered. The book was never intended as a political treatise, but rather as a somewhat rambling commentary on events that were still unfolding. This, though, is the source of Burkean conservatism.

It is a work that right wing thinkers continue to mine for nuggets of insight. But if the remnants of the Conservative Party are searching for inspiration in the hope of reviving its corpse, they probably shouldn’t look to the man who wrote this:

“The Age of Chivalry is gone. That of sophisters, economists, and calculators has succeeded; and the glory of Europe is extinguished for ever. Never, never more, shall we behold the generous loyalty to rank and sex, that proud submission, that dignified obedience, that subordination of the heart, which kept alive, even in servitude itself, the spirit of an exalted freedom.”

Times have changed.