Diogenes the Cynic devised his philosophy of minimalism after watching a mouse that seemed content with a few crumbs of bread and little else. From that moment the philosopher jettisoned his possessions and resolved to live as simply and as naturally as the mouse, sleeping in an old earthenware storage jar outside Athens.

The history of philosophy might have been very different if the mouse he observed was anything like the one caught on infra-red camera in a shed in Wales recently. A video of it went viral last week.

The mouse in question seemed intent on tidying up Rodney Holbrook’s workbench in his garden shed. Holbrook had noticed screws and other odds and ends that he’d left lying around appearing in different places overnight. To his surprise and amusement, when he set up a camera to see what was going on, he discovered the “mouse-proud” rodent moving corks, clothes pegs, and even a screwdriver into a tray. It’s a mystery what the mouse was up to.

What we can be certain of, though, is that the mouse’s apparent tidying instinct has a very different source from Marie Kondo’s. The mouse is not some kind of clutter-nutter interested in surrounding itself only with objects that “spark joy”.

It is anthropomorphism to think of its nocturnal antics as tidying up. This is a mouse, not a person. And besides, it seems to be accumulating bits and pieces rather than getting rid of them. More likely its activity stems from some kind of nest-building instinct, and it is making a home for itself with objects ready to paw.

We’re often told that tidiness is a virtue. I’m not so sure about that. It depends on the context. Some of the greatest geniuses of the last 100 years have produced their best work in messy rooms. Think of the chaotic detritus of Francis Bacon’s studio at 7 Reece Mews, South Kensington, which included pages torn from books, splatters of paint, odd bits of cloth, slashed canvases, discarded champagne crates, old jam jars, paint pots, and clogged up brushes. All this covered the floor knee-deep, so that visitors had to search for a route through.

After Bacon’s death, curators preserved the contents, displaying them as an installation and as a way into the mind and creative process of the artist. This invited the inevitable headline “Mess is More”. Art historians have subsequently studied the old photographs strewn around the studio, discovering new sources for motifs and gestures in his paintings.

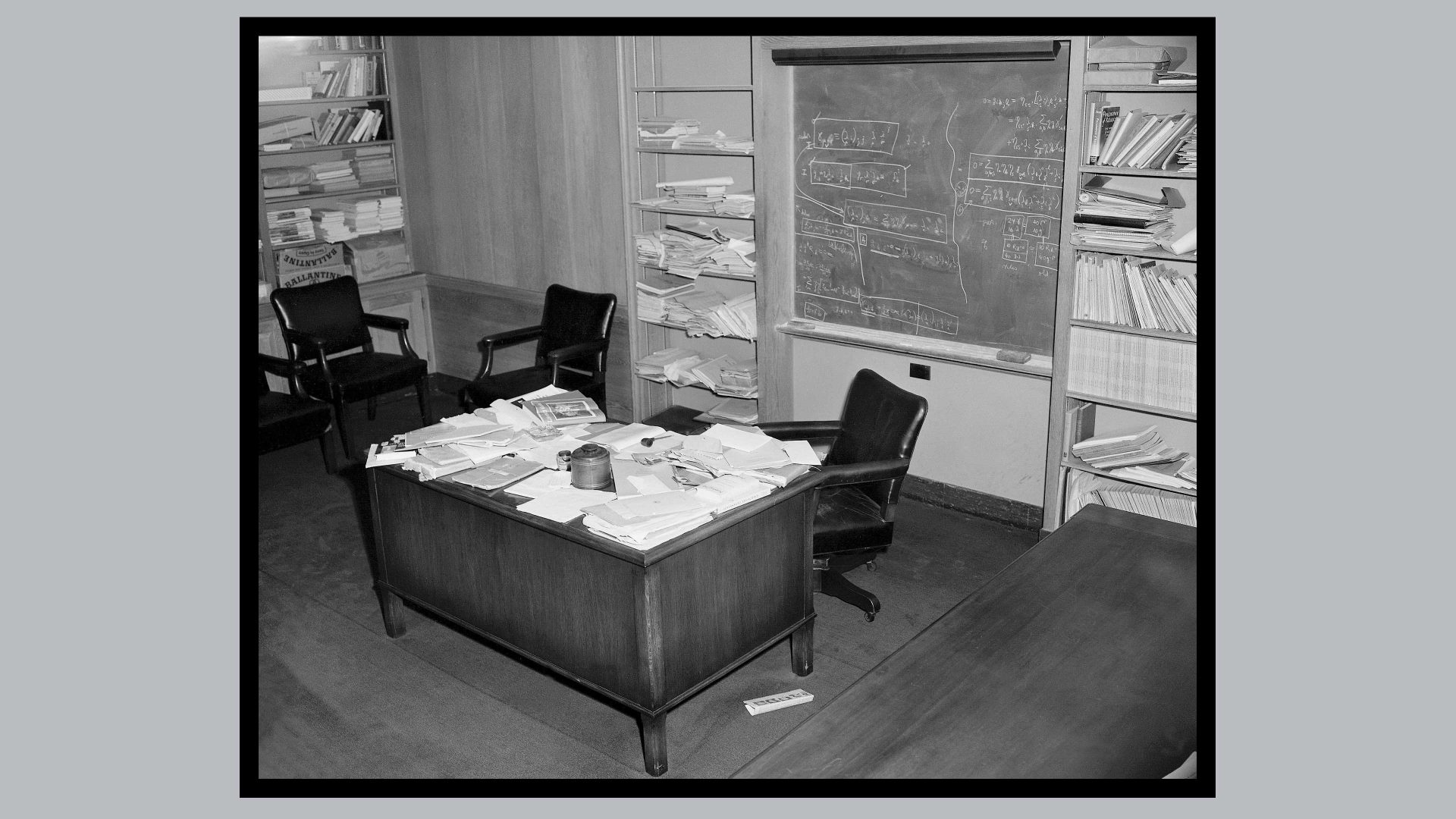

It’s not just in the world of visual art that messy workplaces have proved fertile for creation. Albert Einstein’s office at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton was photographed shortly after his death by Ralph Morse for Time magazine. The physicist whose mind was so organised and clear left a desk that was surprisingly cluttered with papers and books, one that closely resembled Mark Twain’s, to judge from a 1901 photograph of the writer sitting behind a work surface strewn with papers and half-buried books.

Yet few can compete with the developmental psychologist Jean Piaget’s office. Piaget, photographed late in life, looked at risk of being buried alive in an avalanche of old papers and books worthy of a compulsive hoarder.

Philosophers seem to go either way with messiness. Ludwig Wittgenstein’s office in Whewells Court in Cambridge, part of Trinity College, which he occupied in the 1930s, was notoriously sparse, the antithesis of Einstein’s, and almost monastic. A former student, HDP Lee, described it: “There was a table, some chairs; a deck chair, or perhaps two deck chairs; and virtually nothing else. No pictures, no curtains and almost no books. His own writing was done in a large foolscap-size book, bound rather like a ledger.”

Contrast that with the moral philosopher Jonathan Glover’s office, as revealed in a photograph on his delightful website. Glover combines an Einstein-style desk scattered with a Piaget-ish mound of reports and papers that looks at risk of engulfing him from behind.

As someone more at the Glover end of the spectrum than the Wittgenstein one, I’d like to believe that a messy desk is both a result of and a stimulus to creativity. But the truth is that it is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for original thinking. Yet for those of us who are regularly mocked by the house proud, it is reassuring that our paper-strewn desk style is at least compatible with creativity of the highest order. We don’t need that tidy mouse.