Migration is one thing, immigration another. Migrants are temporary, often seasonal visitors. Immigrants come and stay indefinitely. Sometimes regular visitors decide to remain because conditions are good for them, or at least better than conditions elsewhere. Sometimes they continue to come and go, keeping their main bases abroad. Either way, they often greatly enhance these isles in a variety of ways.

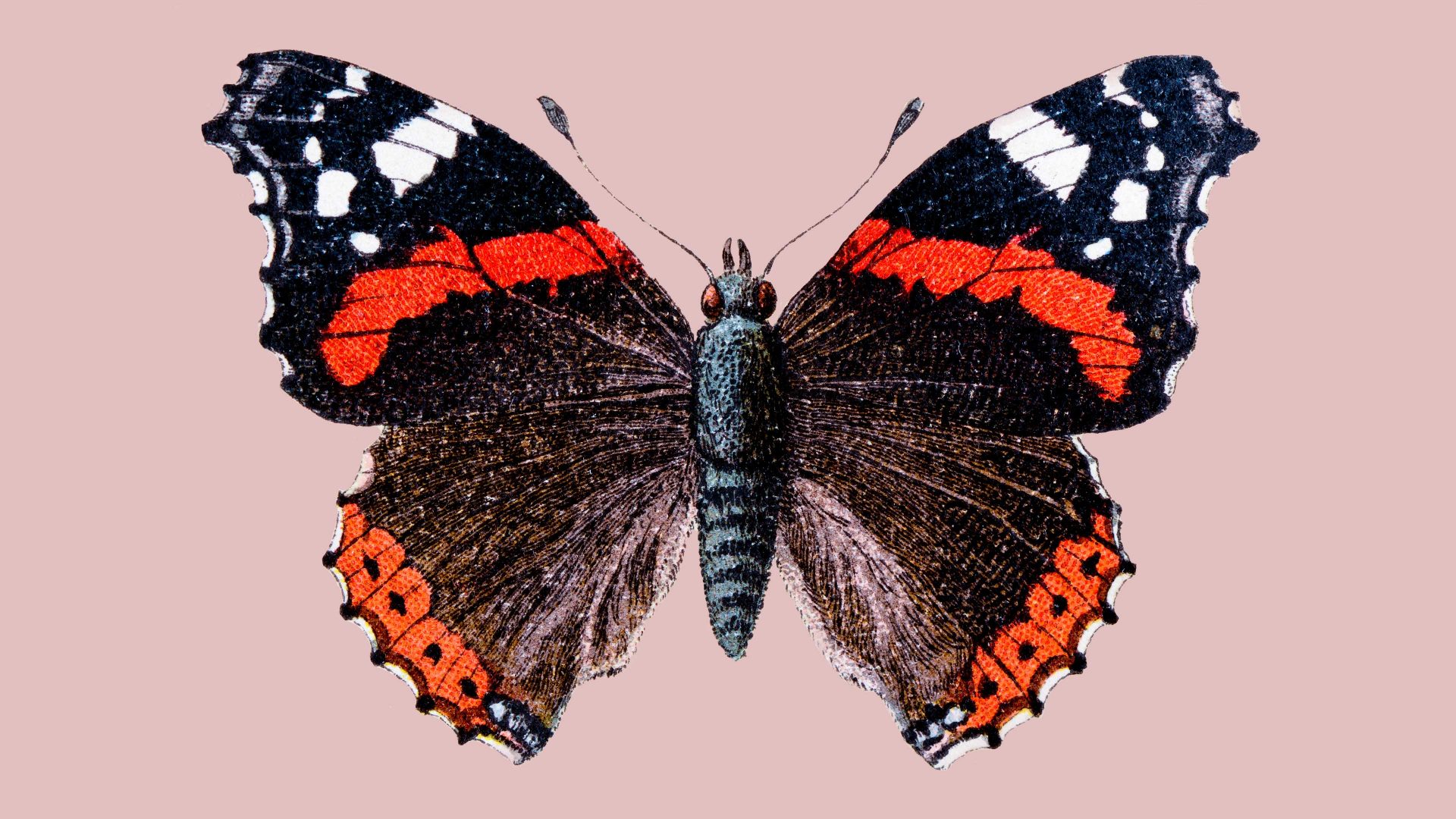

The red admiral, one of the largest, strongest, and most striking of the common butterflies seen in the UK, is in the process of transitioning from regular migrant to immigrant. It seems to be settling in the UK for good. Lucky us. I think it should become a symbol for the kind of immigration that makes all our lives better.

If you’re not a butterfly buff, you probably think of these beautiful insects with their scarlet, black and white markings as native. You’ll have seen them since you were a child, they love feeding on buddleia bushes or sunning themselves on the ground. They’re here every spring and summer and on the wing right through until late autumn, when they feed on rotting windfalls. If they were rarer, we’d probably celebrate them more.

Last year I glimpsed an extremely rare brown hairstreak butterfly – that’s the kind of thing that gives an entomologist a frisson. It was drab by comparison. For me, the red admiral is far more beautiful. They’re everywhere in the south of England, but are found as far north as Orkney. And they’re becoming even more common.

During my childhood, small tortoiseshell butterflies covered the buddleia, but I haven’t seen one this year. Explanations for that species’ 75% decline in numbers since the 1970s include pollution, parasites, and climate change. Yet, as the population of small tortoiseshells dwindles, sightings of red admirals are up 400%. Something is going on. Again, climate change is implicated. It may in the end prove disastrous for butterflies, and probably for us, but in the short term, there is at least one benefit.

Until recently, the first wave of red admirals seen here each year were migrants from continental Europe. They had flown hundreds or even thousands of miles, sometimes from as far away as north Africa. On arrival, they would find a mate, lay eggs, and produce one or two broods.

Come late autumn, recently hatched adult butterflies could be seen feeding in preparation for the arduous journey to continental Europe. A few that failed to migrate south may have managed to hibernate here, but mostly, if they didn’t get to warmer climes, they perished.

With milder winters in Britain, that is changing. The temperatures aren’t triggering those flights to Europe, and they’re staying here all year round. They’ve immigrated, though some will also keep crossing the channel from continental Europe, too.

When non-native species settle here, even attractive ones, it may not always work out well, of course. Grey squirrels were introduced into country estates in the late 1870s as an ornamental addition to stately homes. Cute or not, they’re now classified as an invasive alien species.

They brought with them a squirrel pox that killed many of the native red squirrels. When they compete for food, the greys have a competitive advantage over the reds in that they can digest seeds and nuts before they are fully ripe. Red squirrels are now rare. It’s possible that an increase in the numbers of red admirals will produce analogous problems for species that have been settled here for longer, but at the moment there are no signs of that.`

The rhetoric from the right depicts all immigrants as more like grey squirrels than red admirals. They are presented as a threat to a subset of those already living here. The political philosopher David Miller has argued that restricting immigration may be necessary to preserve a state’s distinctive national culture (whatever that is). Populist politicians and tabloid journalists ramp up fears that immigration lets outsiders jump the benefits queue or take other people’s jobs.

Suella Braverman even uses the language of invasion, and is ever on the lookout for punitive ways to treat asylum seekers and would-be immigrants. She seems intent on creating spectacles of cruelty, whether in Rwanda or Dorset, to discourage others from crossing the Channel. Inhumane treatment is her favourite deterrent. That is straightforwardly immoral. We need far better than this – particularly as soon it won’t just be red admirals whose migratory habits are affected by the climate crisis.