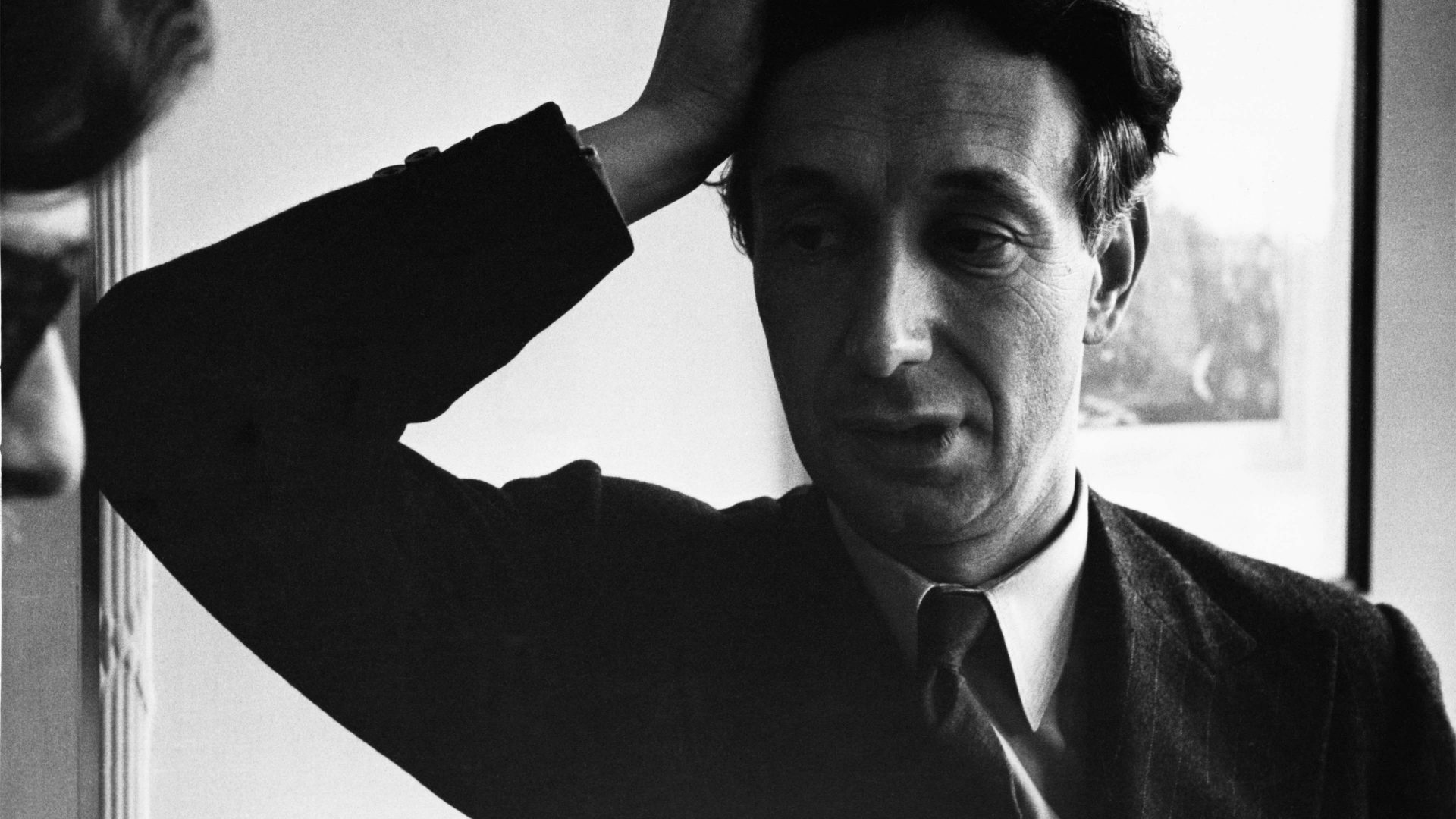

Alfred Jules Ayer, known to the world as AJ Ayer and to his friends as Freddie, died on June 27 1989. He didn’t live long enough to see the fall of the Berlin Wall, but much earlier, in 1936, he’d done his own bit of border-changing destruction. This brilliant and witty old Etonian, introduced logical positivism from Vienna to Oxford and, in doing so, transformed the way philosophy was done in the English-speaking world.

As a young man, on the recommendation of his Oxford tutor Gilbert Ryle, Ayer travelled to Austria to sit in on the discussions of the Vienna Circle, a group of scientists and philosophers who met regularly to argue about the limits of human knowledge. Ayer’s book Language, Truth and Logic, published when he was only 25, summarised what he learned there. This wasn’t continental philosophy of the kind we know today. Far from it. Much of that he dismissed as “mere metaphysics”, a term he used as an insult. Indeed, Ayer later called out Heidegger and Derrida as “charlatans”.

Ayer’s version of the Vienna Circle views rested on the Verification Principle, a two-pronged test for meaningfulness. For a statement to be meaningful, it had either to be true by definition (such as “all cats are animals”) or else empirically verifiable (such as “all cats eat meat”). To be empirically verifiable there must, at least in principle, be some kind of test or observation that would determine whether or not a statement was true. The important consequence of this was that there was an identifiable category of statements that are neither true by definition nor verifiable, and so were, according to Ayer, literally meaningless. Such meaningless statements, he conceded, might have poetic value, but most were worse than useless.

Disconcertingly for many old-school dons, Ayer thought much of the history of philosophy was waffle. The borders of philosophy and nonsense needed to be redrawn. Metaphysical claims such as “all reality is one” were neither true by definition nor testable and so fell foul of the Verification Principle. Moral judgments such as “killing is wrong” went the same way.

For Ayer, moral pronouncements like this were pseudo-statements – not real ones in that they did not have a literal meaning apart from as subjective expressions of the speaker’s emotions. “God exists” was a meaningless statement too, according to Ayer, who rejected the Ontological Argument that attempts to define God into existence, and also the Argument from Design which purports to give empirical evidence of divine shaping of the world).

Ayer, then, was an atheist of a distinctive kind, believing both “God exists” and “God doesn’t exist” were meaningless assertions. In the year before his death, though, he had a widely reported wobble about the afterlife, or seemed to. He choked on a piece of smoked salmon, lost consciousness, and his heart stopped beating. He was technically dead for four minutes before medics revived him.

While “dead” though, he had the disconcerting experience of being in the presence of an intense red light which he somehow knew was connected with the government of the universe. Two creatures who had been put in charge of space, had made some kind of mistake, and now space was out of joint. He couldn’t find them, but the creatures responsible for time were nearby. Frustratingly, though, he couldn’t get their attention.

When he came round Ayer was deeply disturbed by this bizarre vision of the masters of the universe. Some of what he wrote about it implied that he had revised his views about life after death as a result. Soon, though, he was back to describing himself as a born-again atheist and dismissing his near-death experience as a vivid dream.

Ayer came to reject the more extreme version of the Verification Principle he’d presented as a young man. In 1976 Bryan Magee asked him about Language, Truth and Logic’s main faults. Ayer replied, laughing, that its most important defect was that “nearly all of it was false.” He went on to explain that the details of his account were wrong or too simple, but, he maintained, the spirit was right.

It took bravery to stand up to the philosophical establishment in the 1930s, but Ayer far excelled that as an old man. At a party in New York, he confronted Mike Tyson, who was forcing himself on the model Naomi Campbell. Ayer told the world champion boxer: “I suggest we talk about this as rational men.” Surprisingly, the tactic worked, and Campbell slipped away.