Aristotle got some things badly wrong. He thought octopuses were stupid, because when he dipped his hand into the Aegean they’d come up to it. Now we know better. They’re far from stupid.

The philosopher and diver Peter Godfrey-Smith, in his wonderful book Other Minds, describes encounters with them as probably as close as we’ll come to meeting intelligent aliens. They are remarkable creatures, though startlingly different from us.

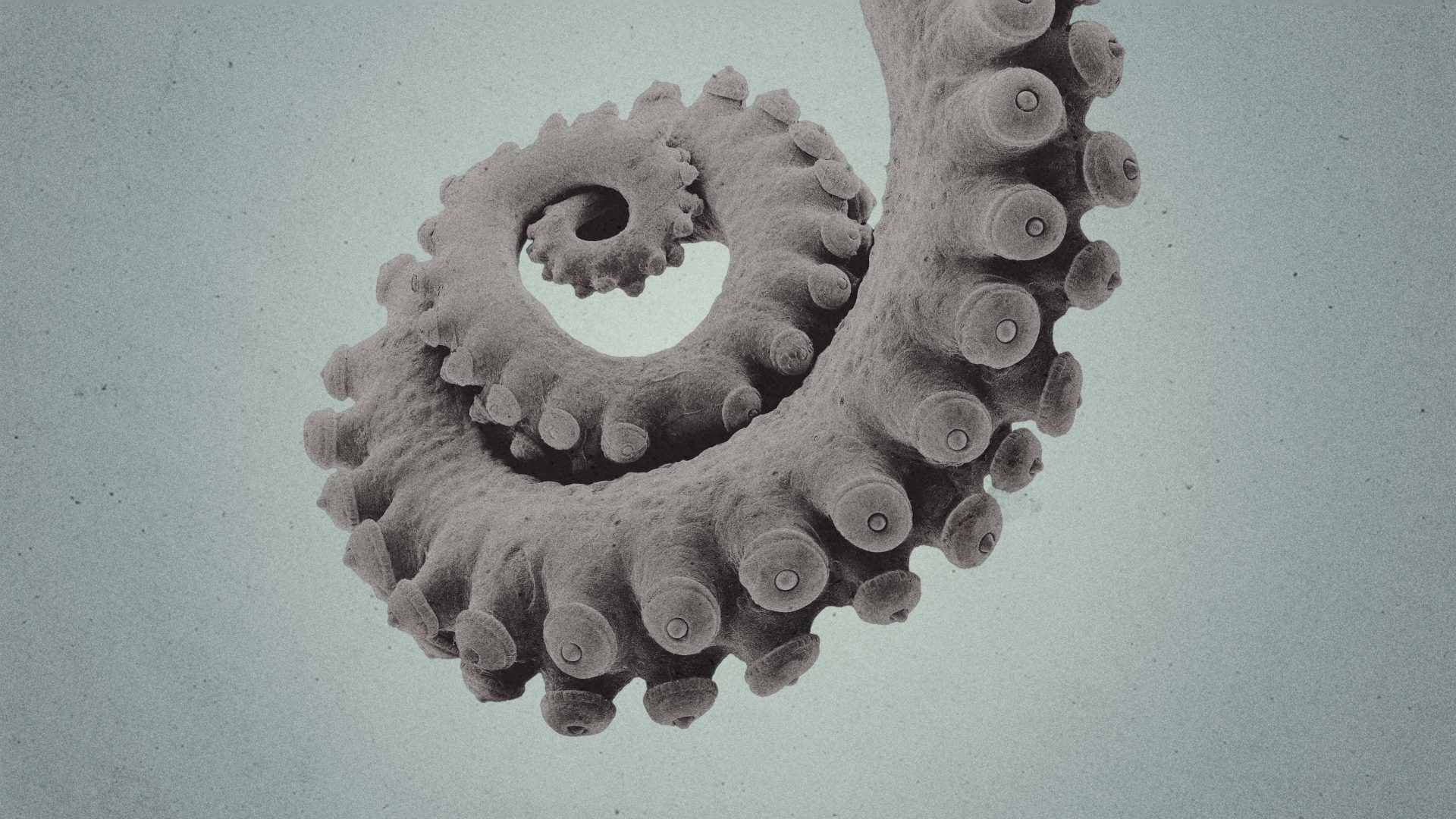

Evolution built minds twice over, Godfrey-Smith suggests, but very differently. Octopuses have more neurons in their tentacles than in their brains. They’re recognisably smart in their way, interact with humans, and even have personalities and moods. They live short lives but learn incredibly quickly. In captivity, some have favourite people, and others they take against, repeatedly squirting water at researchers they dislike. Others are brilliant problem-solvers, finding ingenious ways to escape their tanks. When trapped in a jar, they can even work out how to unscrew it.

Anyone who has watched My Octopus Teacher, the documentary about a diver who befriends a female octopus in an underwater kelp forest off the coast of Cape Town, and visits her regularly till she is torn apart by scavenger fish, will appreciate all this.

Unfortunately for octopuses, though, they’re also delicious to eat, and highly nutritious. Traditionally they’ve been caught in the wild, whether trapped, trawled, or speared. They’ve so far avoided being farmed because their life cycle is quite complicated, and because when kept close together they tend to attack and eat one another. But now that looks set to change.

There is serious concern that a huge octopus farm run by a Spanish company, Nueva Pescanova, will soon open in the Canary Islands, aiming to produce 3,000 tonnes of octopus flesh a year.

Critics of the octopus farm argue that it is impossible or at least impractical to rear octopuses for food without causing them intense suffering. These intelligent, solitary animals need space, and stimulation from their environments, to flourish, not barren communal tanks. What’s more, the proposed method of killing them in icy water may cause them intense and prolonged agony.

The company claims farming will benefit wild populations, some of which are threatened. But that might be wishful thinking. Whether or not it is true, ethical questions remain. For many concerned about animals, the key question is welfare, not whether or not animals are killed for food.

In the early 19th century, the utilitarian Jeremy Bentham argued that our obligations to other animals turn on this key question: “Can they suffer?” The contemporary philosopher Peter Singer has continued in that tradition: while advocating veganism, he has criticised cruelty in food production and campaigned to eliminate factory farming.

In general, the more intelligent an animal is, the less comfortable many of us feel about eating it. But we’re often inconsistent about this.

Eating monkeys or dogs feels just wrong. But many people still happily eat pork, despite knowing that pigs are highly intelligent. In France some people still eat horse meat, but who could doubt the intelligence of horses?

Bentham’s insight is relevant here – we should probably be focusing on animals’ capacity to suffer rather than their reasoning abilities. At the very least that means eliminating some cruel methods still used in animal farming, such as cramped conditions, debeaking hens, or the long-distance transporting of sheep in lorries for slaughter.

If octopuses can’t be reared humanely and are killed in a way that causes them intense pain, then there are strong ethical grounds for banning the import of farmed octopus flesh, and campaigning for the closure of any octopus farm, irrespective of the intelligence of these animals.

Some philosophers take a stronger stance. Gary Francione, for instance, is an animal abolitionist. He believes focusing on animal welfare is a mistake. That’s like campaigning for better housing for enslaved people. Slavery is morally wrong, period. It involves treating people simply as means to an end and not respecting their sentience.

Similarly, any mere use of an animal, such as rearing it for food, should be morally unacceptable. Animals are not chattels but sentient beings that have an interest in keeping alive. Killing them, even painlessly, causes unacceptable harm. Francione’s conclusion is that we have a moral obligation to be vegans.

I’m not persuaded by Francione’s absolutism, but am still worried about octopus farming. It may prove impossible to raise these wonderful animals without cruelty. If that’s so, we shouldn’t eat their farmed flesh: that would be morally wrong no matter how good it tastes.