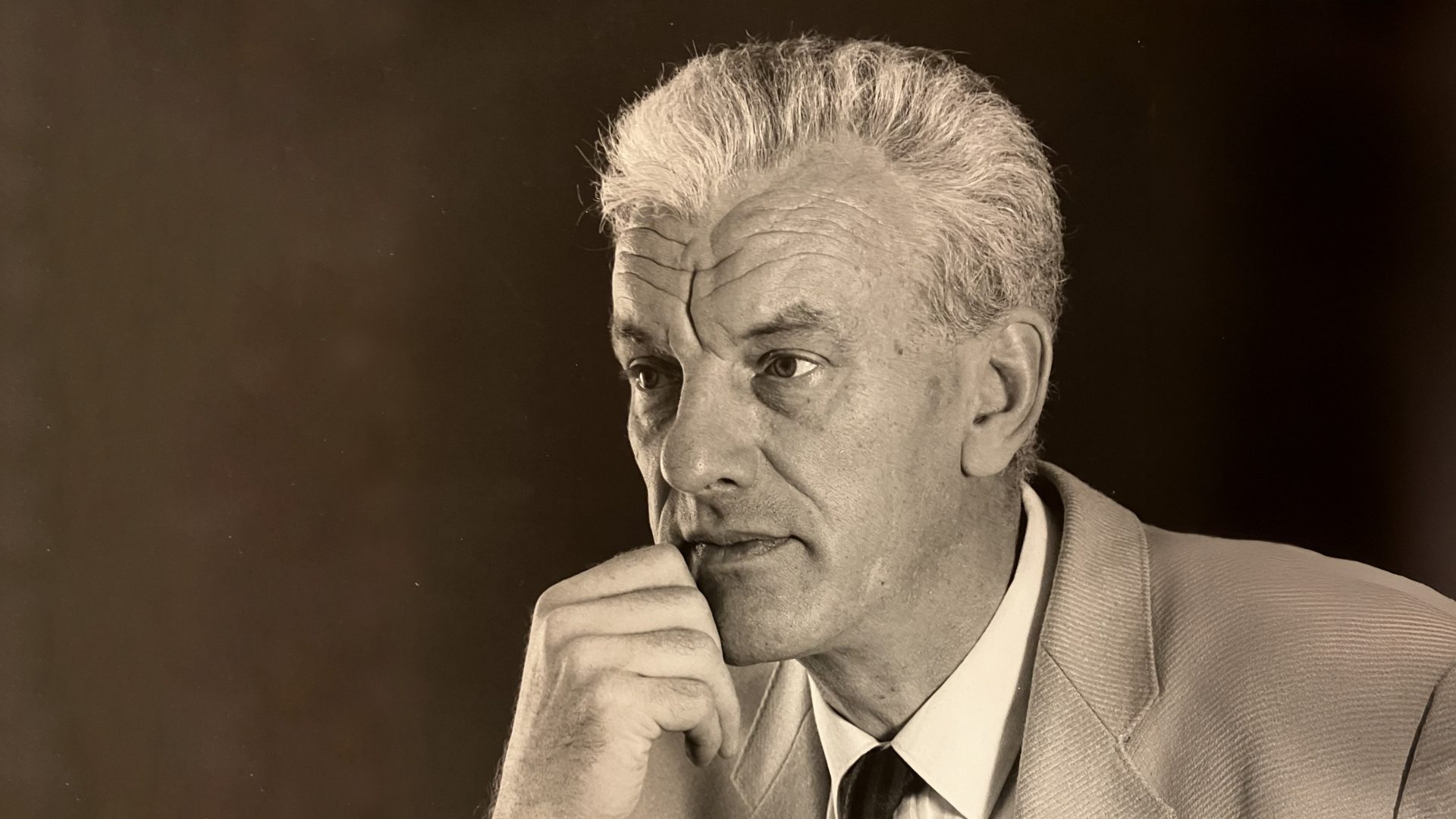

Don Cupitt died on January 18, aged 90. He was an unusual and original thinker. Despite being a practising Anglican priest at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, he didn’t believe in God’s existence – not in any conventional sense at least. He dismissed carols as “the Disneyfication of Christmas”. Cupitt was a non-realist about God – meaning he didn’t believe any great, good, all-powerful metaphysical being existed, and he rejected the supernatural aspects of Christianity, including the idea that souls live on after death.

I first came across him through his 1984 BBC TV series The Sea of Faith. This took its name from Matthew Arnold’s On Dover Beach which includes the lines:

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long withdrawing roar

The poem, published in 1867, describes the loss of religious faith in the Victorian era. For Cupitt, it provided the core metaphor for the TV series.

In modern society the tide had gone out on Christianity, and with good reason. Its key beliefs couldn’t withstand the developments of modern science and philosophy, particularly the insights of Darwin, Kierkegaard, Marx, Nietzsche, Freud, and Wittgenstein.

But, Cupitt, far from despairing, saw this as a reason to reinvent Christianity without its more dubious supernatural elements. That didn’t go down well with traditional realists about God. Some treated him like a heretic.

Cupitt embraced the fact that God is a human invention, but rather than becoming a Dawkins-like sceptic, he celebrated Jesus’s teaching about caring for the poor and turning the other cheek. For him the New Testament was a source of goals not a handbook for salvation.

He developed a spiritual yet godless Christianity that he believed was intellectually respectable because it was compatible with modern science, psychology, and philosophy; and he continued to practise as a highly unconventional Anglican priest, despite not believing the literal meaning of the Creed. More conventional believers thought he was a hypocrite.

In the eyes of these old-style Christians (whom he described as clinging to a medieval pre-scientific model of faith), Cupitt had simply abandoned God and become an atheist, and a dangerous one at that. He’d have probably accepted that description. But he chose not to abandon religion altogether since he still found guidance in Christian teaching, and for him God remained a symbol of moral goodness.

The rites of Christianity were important to him too. Religion, he believed, was an individual spiritual quest, not a set of grand answers to big questions. His was an existentialist ethic, where human beings must each decide for themself how to live.

He strongly opposed the idea that religion requires learning eternal truths which have been passed down via the Bible and other religious texts. He once described his own approach as “Quakerism squared”.

He would have applauded Bishop of Washington Mariann Edgar Budde’s sermon last week on the need for love, compassion, and mercy; the broadside from the pulpit that made Trump and co squirm. But unlike the Bishop he would not have seen this as requiring God’s help: achieving unity that accords everyone dignity is a human task, perhaps the most important one.

Expressing this in religious terms is a way of focusing what is essentially a humanistic ethic of respect. No doubt atheists sympathetic to Budde’s message interpreted her words in that way too, separating the ethical message from its supposed religious underpinning.

Unfortunately, in later life Cupitt fell under postmodernism’s spell and came to embrace the view that all language was little more than the free play of signifiers. That diluted his non-realism about God considerably since he had by this stage become a non-realist about everything else too, not just about the existence of a supernatural being with quasi-magical powers. But his earlier views continued to exert a strong effect on many people who thought deeply about the status and source of their own religious beliefs and yet weren’t prepared to abandon Christianity altogether.

I always felt Cupitt should have taken the next step and freed himself entirely from religion. Christianity without belief in God is a contradiction, and discussing ethics in religious terms, which carry their own historical connotations, is likely to cause misunderstanding. But in these dark days we desperately need an ethic of fellow-feeling. Cupitt was right that you don’t have to believe that Jesus was divine to recognise the wisdom of his imperative “Love thy neighbour”.