Roland Barthes died on March 26, 1980 after being knocked down by a laundry van a month earlier while stepping on to a street in Paris. He had been a key figure in semiotics, the philosophical movement that focuses on the interpretation of signs and symbols and had endeared himself to readers with his accessible and interesting essays on a wide range of subjects, including professional wrestling, striptease, advertisements, and the cover of Paris Match.

In his 1967 essay The Death of the Author, Barthes tried to flip the traditional hierarchy of the writer creating meaning and the reader trying to uncover what the author had placed there. Barthes saw writing from the perspective of the creative reader: the reader projects meanings on to the text rather than decodes a canonical message placed there by its author to be uncovered by the critic.

As he put it: “We know now that a text is not a line of words releasing a single ‘theological’ meaning (the ‘message’ of the Author-God) but a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and crash.”

The text is “a tissue of quotations drawn from innumerable centres of culture”. In other words, all writing builds on past writing and existing codes of expression, and any attempt to explore the “true” meaning the author has given to a text is thwarted by the multiplicity of readings that the text itself sustains. The key that will unlock any text, for Barthes, is not its origin (the author), but its destination (the reader).

The catchy phrase “The Death of the Author” together with Barthes’ hyperbole, meant these ideas found a receptive audience in the 70s and 80s when semiotics was à la mode. But quite similar ideas had been in circulation in literary departments from the late 1940s, inspired by the New Criticism with its emphasis on close reading.

William K Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley had declared war on the sort of literary interpretation that focused on biographical information about authors in their 1949 essay The Intentional Fallacy. Like Barthes, they didn’t believe that a text meant whatever the author said it meant. Intentions that weren’t evident in the text were irrelevant to interpretation. It’s the words on the page that mattered.

The philosopher Stanley Cavell gave a succinct summary of their stance: “It no more counts towards the success or failure of a work of art that the artist intended something other than is there, than it counts when the referee is counting over a boxer that the boxer had intended to duck.”

There’s much more to say than this of course, and the death of the author/anti-intentional stance goes too far. Context, and the conventional meaning of words and other symbols shape meaning, and authorial intentions if known are part of that context, including any declared realised or unrealised wishes for the work.

Some interpretations are wild and should be discounted as fanciful. Others are plausible reconstructions of presumed meaning, even if the author rejects them. Works of art don’t carry single meanings – we enjoy polysemous works, ie those that are open to multiple interpretations. But it doesn’t follow that every interpretation is as good as another.

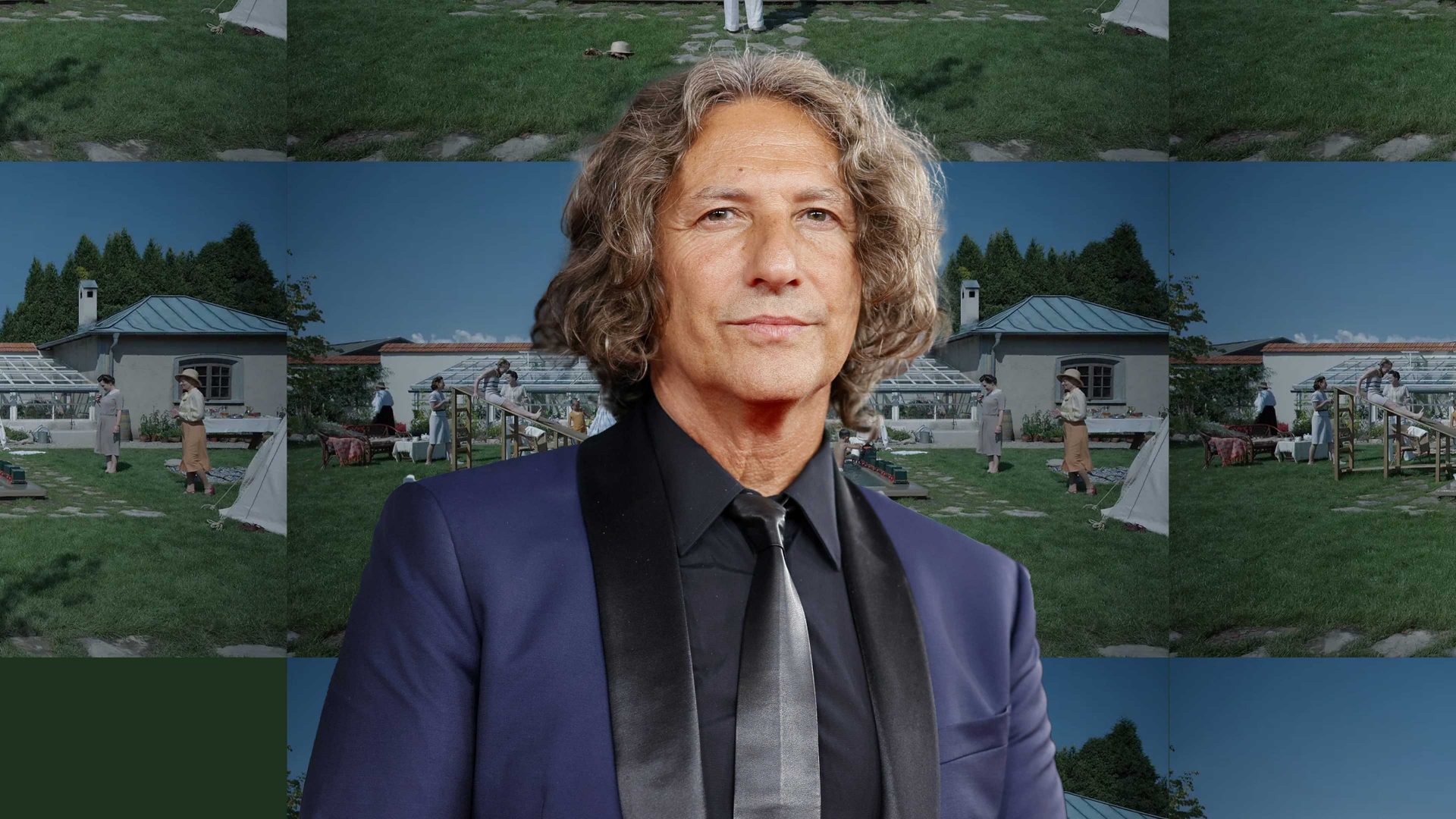

Something that director Jonathan Glazer said in his controversial Oscar speech about The Zone of Interest is relevant here. The film focuses on the family life of Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Höss while mass murder is taking place on the other side of the wall, and on the sustained denial that must have involved.

In his speech, Glazer said: “All our choices were made to reflect and confront us in the present, not to say ‘look what they did then’, but rather ‘look what we do now’.”

When I watched the film, I didn’t see it that way, though. It seemed to be about dehumanisation and denial in the specific context of Auschwitz.

Like any film on that topic, it raised universal questions about inhumanity and what it would take to be a perpetrator of these kinds of crimes, but I didn’t see it as primarily being about the present. In my interpretation that wasn’t foregrounded.

I don’t think I was alone in interpreting the film that way. Did I misread it? Perhaps. And if I watch it again, I will be sensitised to the present-facing aspects.

But what Barthes and the anti-intentionalists did get right, in my opinion, is that Glazer telling us that it is meant to be about the present isn’t what makes that so.