As I sat eating a pizza while looking out through the restaurant window on to Tottenham Court Road on Saturday afternoon, I noticed a man shouting aggressively at a woman. They were standing facing each other. I couldn’t hear them. The woman was frightened and distressed.

She seemed to be a waitress from the restaurant next door. There were people sitting at the table right next to them.

My instinct was to grab my phone to record what was happening and be ready to run to help if the situation escalated, though part of me wanted just to finish my meal and ignore what I was witnessing. Before I could open my phone, though, the man strode off and the woman went back into the restaurant, visibly shaken.

What amazed me about this was that two groups of people sitting at tables outside next to the angry man had just carried on their conversations throughout this as if nothing was happening. But the man had been standing a few feet away from them. They must have been able to hear the aggression in his voice and sense the woman’s fear. She was in tears.

They didn’t even look up. Perhaps they were afraid and didn’t want to aggravate him, but my impression was that they simply didn’t want to know what was going on.

Or rather, it was as if, because they didn’t want it to be happening, they denied to themselves that it was happening and immersed themselves in their conversation.

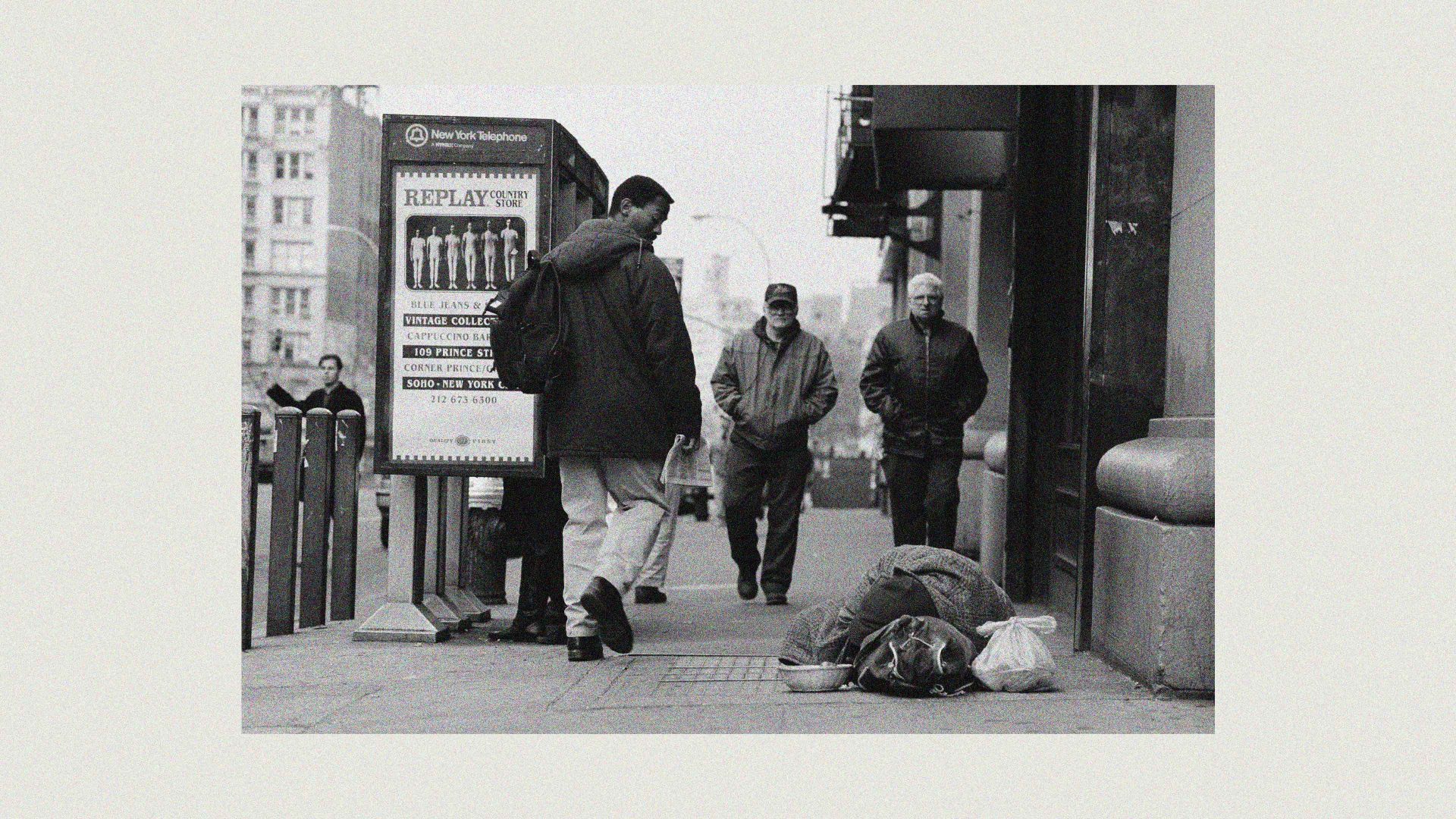

This matched WH Auden’s observation in his poem Musée des Beaux Arts, where he wrote about how the great painters like Breughel were never wrong about suffering: they knew that it takes place “while someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along”.

In his superb book States of Denial, published in 2001, the sociologist Stanley Cohen gives a subtle account of a wide variety of avoidance behaviour. He points out that looking the other way when others are suffering might not imply that we really know what is going on: it could be that we have an idea that something bad is happening, but only have a faint idea of what it is.

“We are vaguely aware of choosing not to look at the facts, but not quite conscious of just what it is we are evading,” he writes.

Cohen was brought up in apartheid South Africa and became fascinated and upset by the denial he saw around him, adults repressing or blocking information that they should find disturbing but somehow didn’t. In his book, he distinguished between internal and external bystanding. Internal bystanding occurs in relation to what is happening near you. External bystanding relates to events happening far away that you learn about from the media.

Internal bystanding is far more surprising and the harder to explain of the two. The information we glean from our own experience is richer and more immediate than from videos and news stories that invite us to be voyeurs of others’ far-off suffering, “tourists amidst their landscapes of anguish,” as Michael Ignatieff describes us.

Cohen observes somewhat bluntly: “It is quite abnormal to know or care very much about the problems of distant places.” Sadly, despite the best efforts of effective altruists and others, that remains true. But when people are suffering near you, around you, in front of you, you might imagine that would be hard to deny or turn away from.

Yet it isn’t. In the 1980s, an American historian, Gordon Horowitz, interviewed villagers who had lived around the Nazis’ Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. Many of them claimed that although they had seen and smelled smoke from burning bodies, and heard rumours about the camp’s purpose, they hadn’t really known what was going on there.

Later it wasn’t so much that they had forgotten what had happened, but rather that they had never attempted to find out.

They just carried on with their own business. Perhaps they were indifferent to what was going on, or even approved of it. Or maybe they felt that if they had found out they would have endangered themselves.

But some had certainly been in this strange but common state of denial, of avoiding knowing what they really knew, or at least of avoiding thinking through what it meant, because that would have been too painful and too disturbing.

Like the bystanders in Auden’s poem, they just got on with their lives, not particularly troubled by suffering around them. They had other things to do and think about.