It is time to rethink what we are. We need to rid ourselves of the lingering remnants of the view that human beings are souls inhabiting bodies that Gilbert Ryle mocked as “The myth of the ghost in the machine”. René Descartes usually gets the blame for this implausible account of the relationship between mind and body. He argued that I can be more certain of my own existence as a thinking thing than of the existence of my body. For him we are conscious thinking things tout court, and bodies are merely shells for souls. But the truth is we are physical beings and most of the ways we interact with the world and with each other take place under the hood – the machinery does its work and relatively little seeps into consciousness. Feelings shape what we do, and feelings arise from our interactions with the world, and, surprisingly, from our monitoring of changes in our bodies.

In the late 19th century William James and Carl Lange independently came up with the idea that with emotions physiological changes are primary. It’s not that we meet a bear, are frightened, and so run away, but rather that we tremble and are afraid and run. Without the bodily changes we’d have a belief about a bear and a judgment that we should flee, not a feeling of fear. Every emotion involves “bodily reverberation”. As James put it, “a purely disembodied emotion is a non-entity”.

James and Lange had only introspection and crude empirical data to back their hypothesis. But contemporary neuroscientists are getting excited about the related phenomenon of interoception and its unexpected role in our lives. Interoception is our sensing of our internal bodily states, processes, and changes. This needn’t be conscious. For instance, we monitor our heartbeats constantly to maintain homeostasis, that state of self-regulated equilibrium that is a prerequisite for life. At times we may become consciously aware of the beating – during or after vigorous exercise, sex, or gardening perhaps. But most of the time we aren’t consciously aware of this unless there’s a sudden change, such as a palpitation.

Why does this matter? Surely our internal bodily monitoring system can just get on with that and we don’t need to worry unduly about it unless something goes wrong? Perhaps. But there are fascinating details emerging from the work of Antonio Damasio and others that suggest such sensing (of our heart, viscera, skin resistance, our breathing and many other aspects of our bodies) has a strong connection with the accuracy of our gut decisions, our wellbeing, our emotional states, and our general mental health.

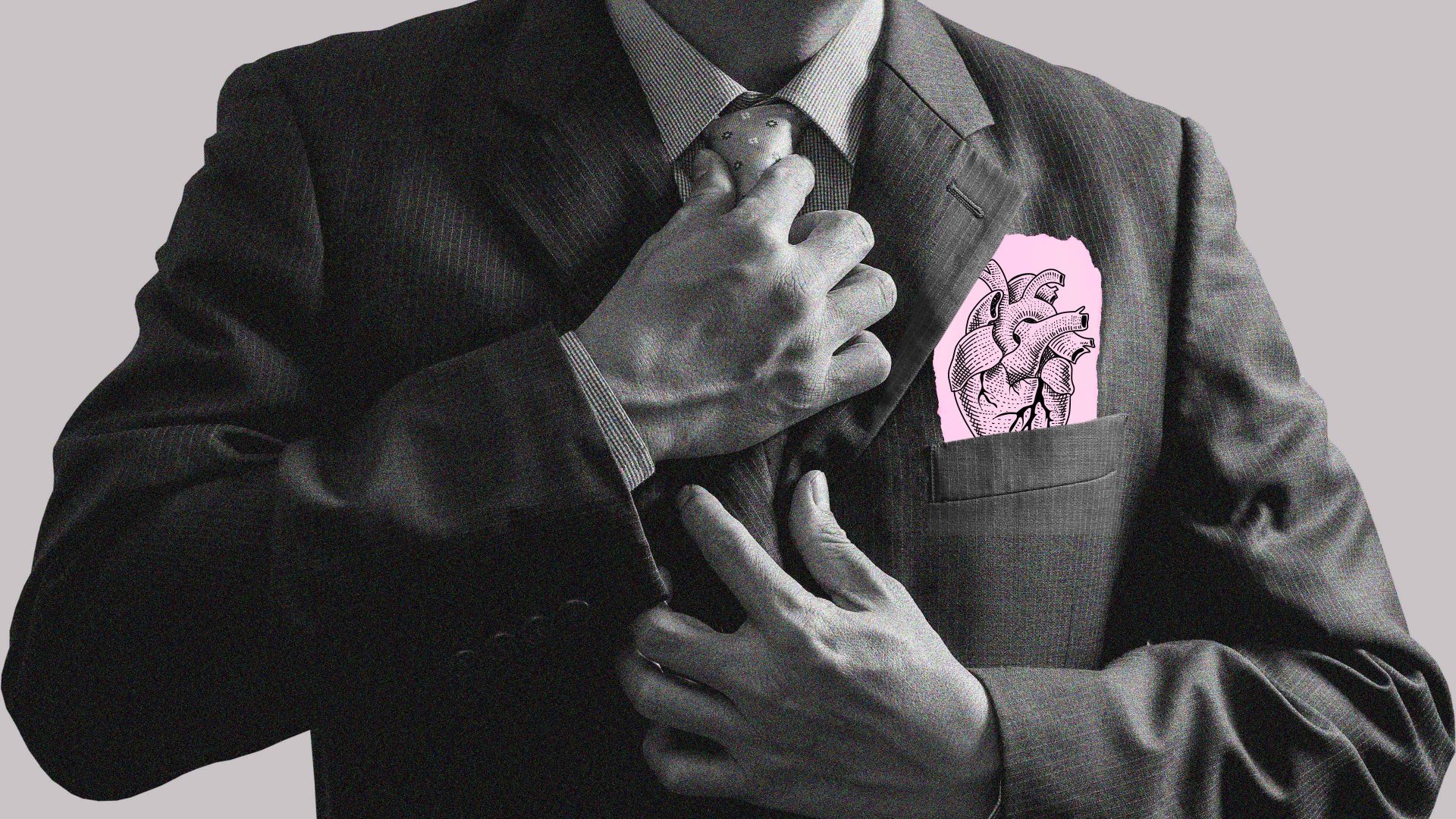

Let’s go back to the heart. Some people are much better than others at monitoring their heartbeats – when asked they can give a very good estimate of that. The neuroscientist Sarah Garfinkel did research on a group of London financial traders making high-risk decisions and found that they were better able to perceive their heart rates than people matched with them for age and sex in a control group. Not only that, but their interoceptive ability in this dimension accurately predicted how much money they made. Those best able to sense their own heartbeats turned out to be the most effective traders in terms of the returns they made on their decisions to buy or sell.

These traders act very quickly and have to rely on gut instincts. There isn’t time to reflect consciously on which are the best options and which trades to avoid. But gut instincts in this case are probably responses to subtle changes in their heart, not their guts, changes they may not even be conscious they are sensing. This interoceptive sensitivity seems to contribute to their effective risk-taking. It’s part of what makes a decision feel right or risky. The interplay between the rest of the body and the brain guides the good decisions here, not in some mysterious way, but based on an accumulation of feedback from previous good and bad trades. Effective traders have formed neural pathways and corresponding physiological responses that make their gut decisions better. But they’re also better than other people at detecting the signals the heart sends them about these decisions so that the wisdom is delivered as a feeling rather than a conscious set of pros and cons about what to do. Their hearts tell them something and they listen.

We don’t usually talk about thinking with our bodies. But perhaps we should.