Yesterday was Albert Camus’s birthday. His stock was high during the pandemic: everyone was reading La Peste (The Plague), a novel that has uncanny parallels with how things unfolded under lockdown. I read it for A-level French back in the late 1970s and didn’t really appreciate it at the time. Now I do.

Back then L’Étranger (translated as The Outsider, or sometimes as The Stranger), with its existential themes, was the one to read. The alienated central character Mersault doesn’t seem to care about anything (his mother’s recent death, shooting and killing a man on a beach) until faced with the prospect of his own death. Like Jean-Paul Sartre (whose novel Nausea was less compelling), Camus reflected back at us the utter meaninglessness of existence: no god, no objective values, a sense of anguish and absurdity.

Born in Algiers in 1913, a pied noir (a white descendant of European colonialists), Camus went on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1957. He was the first person born in Africa to do so. He embraced life, playing football (as goalie for the Racing Universitaire Algerios junior team), dancing, swimming, and spending time on the beach with friends. Tuberculosis set him back, but it didn’t prevent him being active in the wartime resistance in Paris, where he edited and wrote for the underground magazine Combat. He was a successful novelist and theatre director, wrote for the newspapers, and hung out in cafes with Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir – until he fell out with them. He was also in favour of a European federation – an attractive trait.

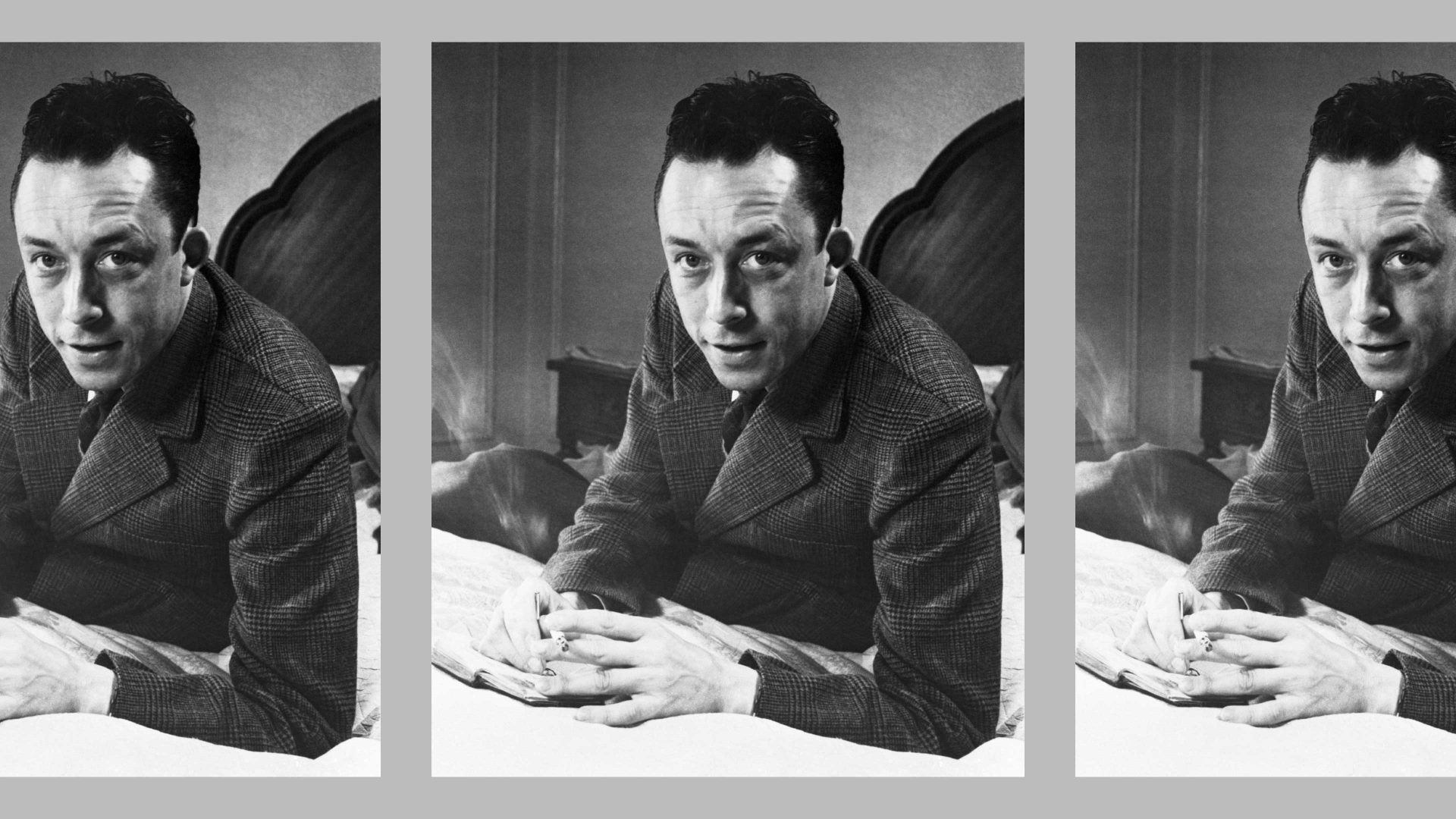

But above all he was handsome. Possibly the best-looking philosopher so far. Women found him irresistible, and he had numerous affairs, including a long term extra-marital relationship with the Spanish-born actress María Casares. He looked like a philosophical Humphrey Bogart, with his slicked back hair and dark and quizzical stare. He could easily have been a movie star.

Sartre, who was short, cross-eyed, had bad skin, didn’t care for his teeth, and wasn’t overly concerned with personal hygiene, relied on his silver tongue and existential credentials to seduce women; that worked for him. Camus didn’t need to say anything for women to be enchanted by him. His bedroom eyes would do the trick. Sartre thought that a human being was ultimately “a useless passion” and love either a form of sadism or masochism – a character in his play Huis Clos (No Exit) declares that “Hell is other people”. He was a pessimist in many respects and emphasised the anguish of existence in a world without pre-existing values.

He was also a far better philosopher than Camus, as was de Beauvoir. Camus was more cheerful about our lot: he told us that we should embrace the futility of existence and imagine that Sisyphus was happy with his fate rolling his rock up the mountain only to have it roll right back down again every day for eternity.

Perhaps there is a connection between Camus’s good looks and his optimistic response to the absurdity of the human predicament. Lookism is a well-documented phenomenon. In many aspects of life people who are by consensus physically attractive get treated better than those who are rated ugly, disfigured, or unattractive. It’s a very widespread form of discrimination and we’ve all seen it happening.

Life isn’t fair in this respect. It first makes some people better looking than others, and then prejudices other people favourably towards them, often without their realising that they are giving them special treatment. Academic research has shown, for example, that people rated as physically attractive are more likely to get job interviews, be hired, and then promoted and paid more, than those perceived as less attractive.

Doors open for those who, like Camus, have ridiculously good looks. Perhaps it’s easier for them to be optimistic because of this. The world treats them better. And Camus’s looks continue to work for him even after his death (he died at the age of 46 when a sports car in which he was a passenger crashed into a tree).

Articles illustrated with Henri Cartier-Bresson’s iconic 1944 photograph of the young philosopher with his coat lapels up, turning to face the photographer, a cigarette in the corner of his mouth, still draw the eye.

People still get a crush on him, and not just sapiosexuals. His image on the cover of a book can still help sell it. He is a publisher’s dream. Perhaps, though, this is further evidence that Camus was right: the world is absurd.