“How should we live?” is the most fundamental philosophical question and the hardest to answer. Some find external props in religion or convention, but many of us have to experiment quite a lot to discover an adequate response, or at least to work out what we definitely don’t value.

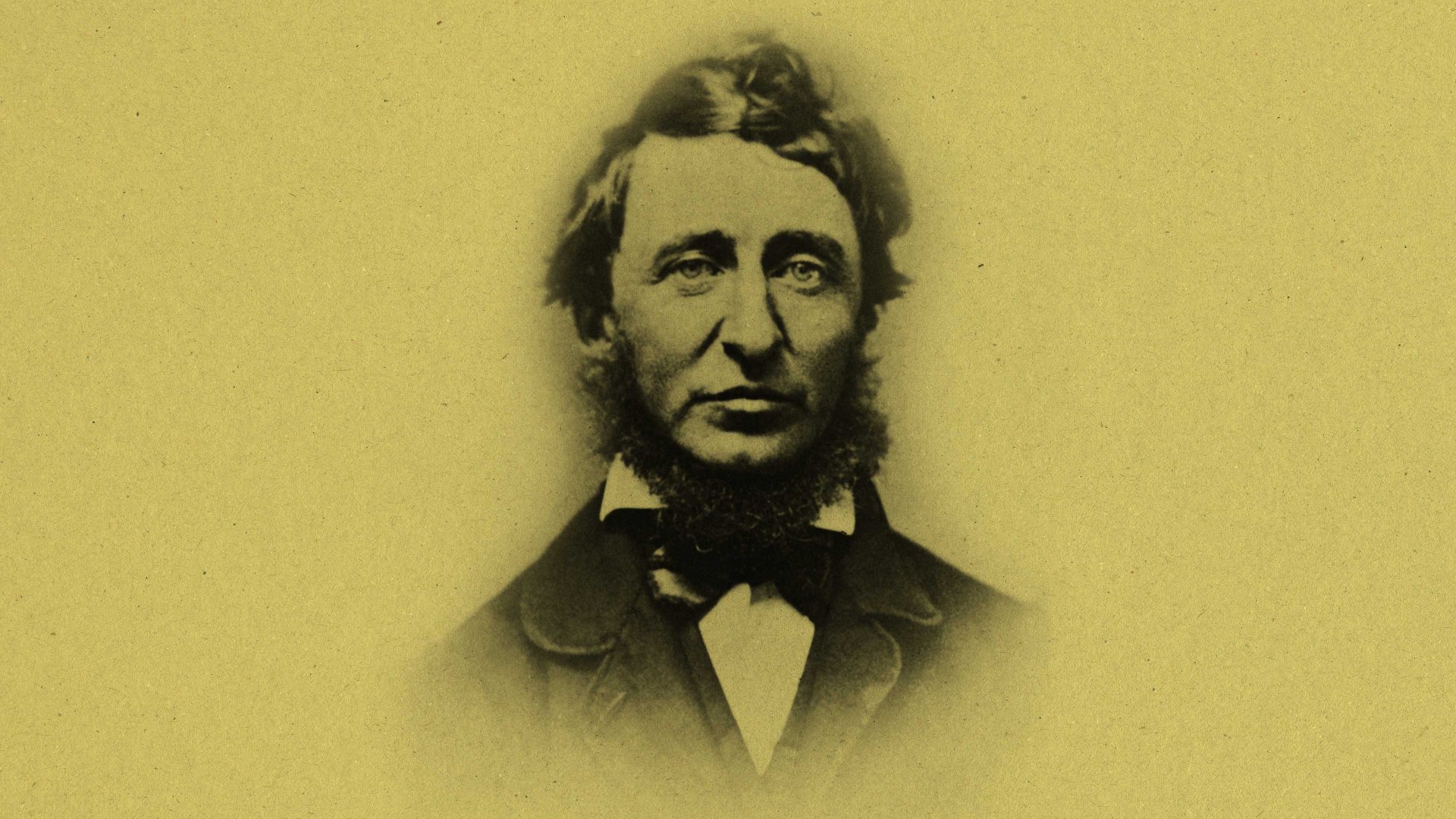

Born on July 12 in 1817 in Concord, Massachusetts, Henry David Thoreau conducted an interesting experiment in how to live by spending two years and two months in a hut by Walden Pond (really a small lake) from July 1845. The journal he kept was the basis of his book Walden.

Thoreau was heavily influenced by his friend and mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson, who combined a reverence for nature with a passion for self-reliance and living in the present. He also, conveniently, owned the land where Thoreau set up his hut.

Thoreau described what he was trying to do:

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

Most people led lives of quiet desperation, he felt, struggling to exist economically and spiritually, trapped in a web of obligations, conventions, and responsibilities that prevented them from seeing their plight. Before they knew it their lives were ending. He didn’t want to be like them. Real human necessities, he felt, boiled down to food, shelter, clothing, and fuel. So he downsized to a minimum, growing a few rows of beans, foraging for edible plants, chopping his own firewood, and spending most of his time walking, reading, writing, or meditating. Above all he was a close observer of the plant and animal life around him.

Thoreau wasn’t a purist about this isolation though. He would walk into nearby Concord several times a week, have long conversations with locals, and even took his washing home to his mother. He had visitors to his hut, too. This all bugs some people because they think he had decided to become a hermit. But he hadn’t. He had chosen a spot less than two miles from his hometown and could hear the trains passing nearby. This wasn’t untouched wilderness or desert. Far from it.

“Our life is frittered away by detail,” he wrote. The way to live well was to live simply. He had ascetic tendencies and relished the Spartan aspects of his life in the woods, enjoying his self-sufficiency and near independence from those living in nearby towns. But he didn’t starve himself, or sleep rough, or stop talking to other people.

In all his time at Walden, he claimed only to have felt lonely once, for an hour soon after he first arrived, but that was dispelled by the sound of softly falling rain outside his cabin. The rain gave him a sense of a benevolent nature all around him and that lifted his mood. From then on it was self-reliance all the way.

Can and should we learn from him? Yes and no. Yes, we can learn from his sensitivity to nature: often we are too busy to notice what is in front of us. Walden is a reminder not to let ourselves be so preoccupied that we miss the beauty and soul-restoring potential of quite modest amounts of time in the countryside or even from just watching a butterfly alight on a flower in a city park.

And he is surely right that many of us waste our lives pursuing material things that are spiritually worthless. But his celebration of self-reliance and rugged individualism is worrying. Going it alone doesn’t work for individuals any better than it works for countries. We can’t so easily dispense with community and human relations. Not without paying a high price.

One critic, Kathryn Schulz, declared Walden “a fantasy about escaping the entanglements and responsibilities of living among other people”.

To be fair to Thoreau, his brother had died from tetanus a few years before he began living in the woods, so his escape to Walden may have been partly a way of coming to terms with that.

And he did, in the end, return to Concord rather than remain an outsider growing beans by a lake. His given reason for leaving was that he had other lives to live.

But perhaps the best interpretation is that his experiment taught him that self-reliance wasn’t everything, and that ultimately living well involves living among other people.