Over a period of 30 or 40 years, the sculptor Alberto Giacometti was photographed hundreds of times. His studio on Rue Hippolyte-Maindron in Montparnasse – “the cave” – became legendary, its archaeology of paper, paint, clay and cigarette ends accreting in a way similar to the marks and material of his art.

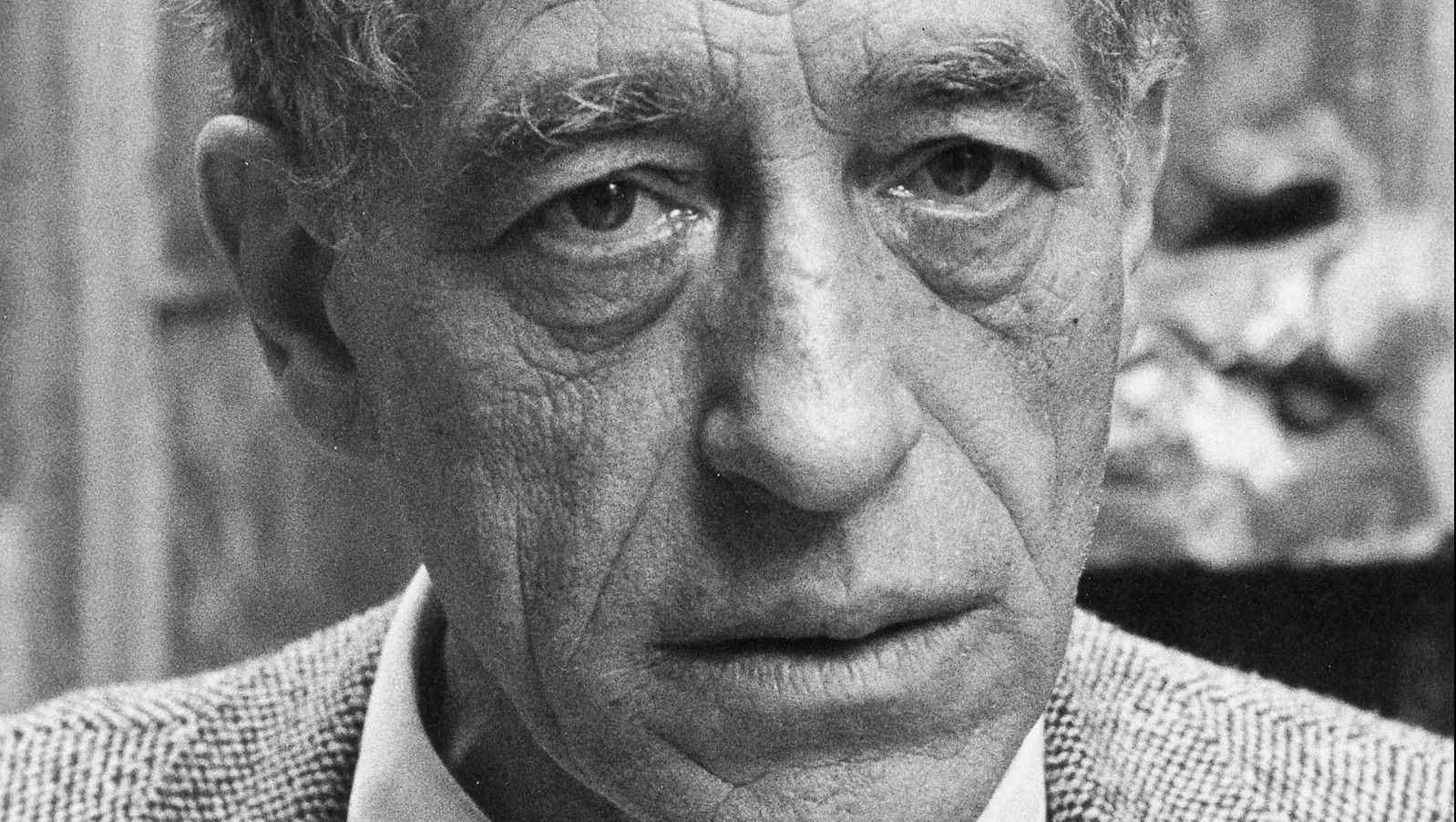

Among the many great photographers dispatched to document this astonishing place – and they included the greats Henri Cartier-Bresson and Inge Morath – Giacometti’s fellow Swiss, Ernst Scheidegger (1923-2016), stood out.

It was the “Scheideggeresque gaze”, as Giacometti called it, that fashioned the artist’s public image, and in the process of creating the most extensive archive of photographs and films on the sculptor, the pair became firm friends.

Simultaneously highly stylised and, as Giacometti himself said, “a little like a reportage, but very special”, the portraits of Giacometti are Scheidegger’s most celebrated work, which includes portraits of Dalí, Miró, Ernst and Chagall, among many other contemporary artists of his era.

Following the centenary of Scheidegger’s birth in 2023, the artists’ portraits have been brought together at MASI Lugano, Switzerland, in an exhibition titled Eye to Eye, curated by Tobia Bezzola and Taisse Grandi Venturi. The portraits are presented alongside paintings and sculptures by the artists themselves, allowing visitors to appreciate Scheidegger’s unique ability to infuse his quiet portraits with the character of each artist’s work.

As Scheidegger’s most celebrated and long-standing subject, Giacometti is afforded a room of his own, in which the two artists are “eye to eye” in both senses of the phrase, facing each other across the gallery, and engaged in a mutually enriching dialogue.

In a view of the studio photographed from above, Giacometti’s silhouette is as provisional as the lump of clay on its board, an empty easel, or a heap of overalls discarded on the floor.

In contrast, Pointing Man, 1947, photographed out in the street, has a solidity and “realness” rarely afforded to the artist himself, who often appears elusive and insubstantial.

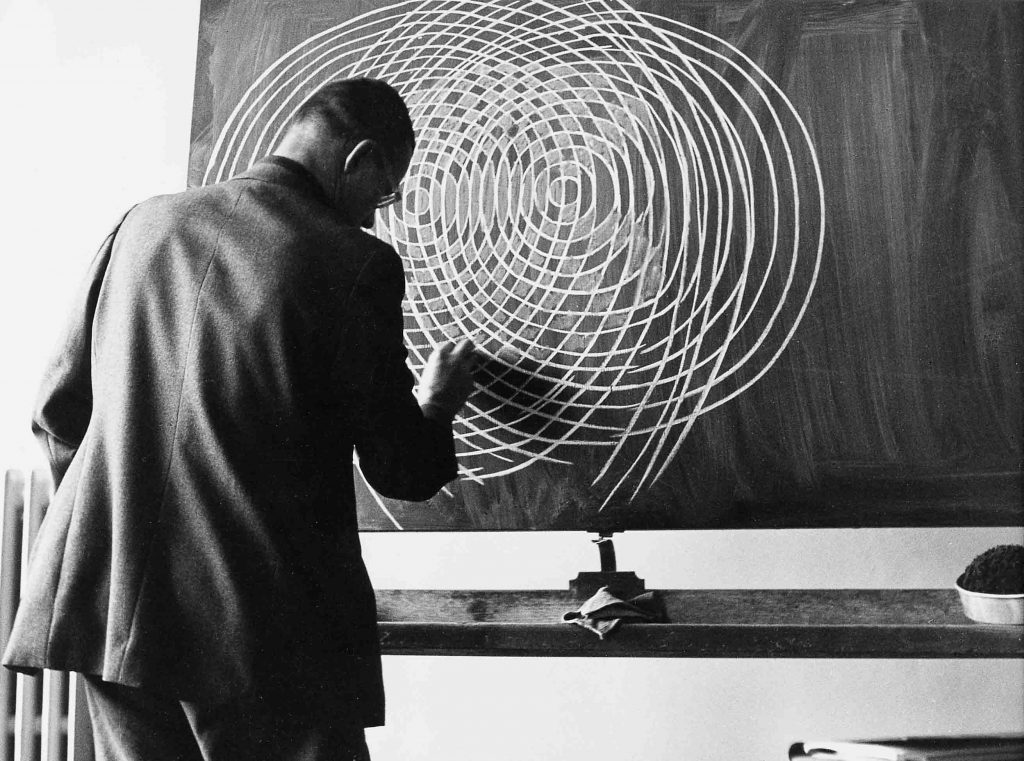

Scheidegger was able to reproduce this effect of a momentary glimpse into an artist’s imaginative world: hunched in concentration, at his desk or semi-prone on the floor, the remarkably expressive figure of Joan Miró echoes the calligraphic, semi-abstract forms of his work.

In his white overalls, Eduardo Chillida becomes one of his own sculptures, while Fernand Léger is as inscrutable and mysterious as his paintings.

In contrast to the monumental formality of these portraits, Scheidegger finds warmth and even humility in Salvador Dalí. Photographed in 1970, Oskar Kokoschka is an affable old man; in 1974, Max Ernst appears almost diffident, his face half hidden in shadow. Perhaps his most moving portraits are of Marc Chagall, whom he photographs in the mid-1950s after his move to the Côte d’Azur where he took up sculpture, using the local stone.

It is no accident that Scheidegger’s portraits register familiarity and even genuine affection between photographer and subject. The remarkable genesis of these relationships, and indeed the development of his subtle, highly characteristic style, is entangled in a complex career path that began in the aftermath of the second world war. It is revealed here for the first time in around 60 photographs from the 1940s and early 1950s that have never previously been exhibited, and have been specially hand printed for the occasion.

Scheidegger was an extraordinary polymath, described in a 1992 retrospective as a “photographer, cinéaste, designer, editor, painter, publisher, gallerist”. None of this seems to have been an exaggeration, and elements of these different callings can be seen in his photographs, which show him to have been a clever and resourceful photojournalist from the off.

As a boy he had access to a camera, but it was drawing that he really loved, and this was his focus immediately after high school, when he enrolled on a foundation course at Zurich’s School of Arts and Crafts.

Concerned about his job prospects, his father insisted that he undertook an apprenticeship designing window displays, training that is surely evident in his early photographs, with their eye for commercial signage and advertising, and lent weight and humour through chance arrangements of figures or street furniture.

While on active service during the war he took his camera with him, so that when he went back to art school in 1945, where he was inculcated with the highly technical, studio-based object photography of his teacher, Hans Finsler, his experiences gave him a diverse and idiosyncratic frame of reference.

According to Alessa Widmer, writing in the exhibition catalogue, the time he spent with Finsler taught him that “object photography held no real fascination for him”, and when in 1946 he, like many of his generation, volunteered to help with the postwar reconstruction of Europe, it set him on the apparently divergent path of photojournalism.

In reality, his photographs make good use of all that he had learned up to that point, and in a street scene titled A butcher in southern Italy (c.1948), he lavishes attention on an eccentric assortment of hams, flowers, bread and hand-lettered signs, the two men on the street corner adding interest mainly as blocks of light and shade.

Similarly, had his eye not been so thoroughly primed to look for pattern and symmetry, Pedestrians in front of billboards and election posters, Milan (c1948), might easily have escaped his attention.

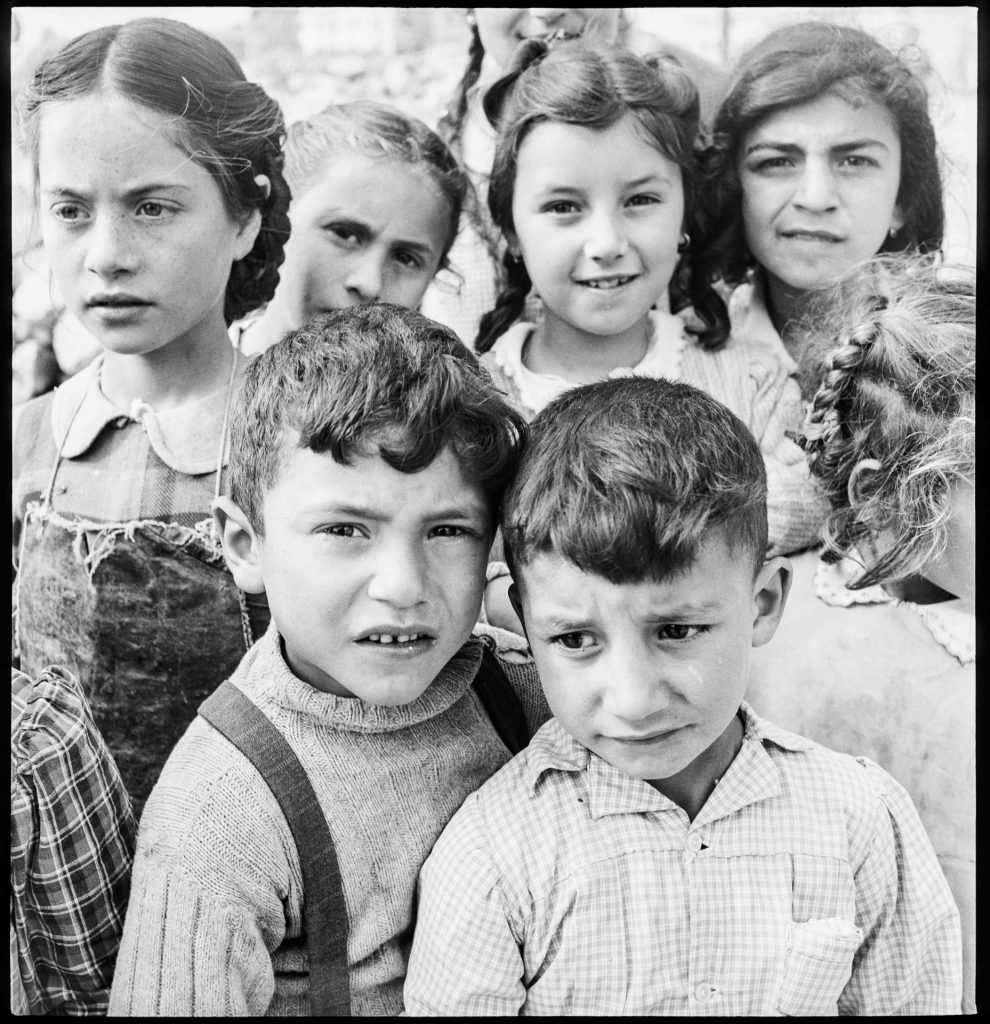

Still, ultimately it was people who interested him, and in photographs of Czechoslovakia, Serbia and Slovenia, geopolitical trauma is captured in the banal details of daily life. There is a distinctly surreal, disjointed element to some of these pictures, and in Postwar reconstruction, Czechoslovakia (c.1946), the mountain of rubble being cleared by filthy men and women seems to occupy a distinct, distant realm from the scene of orderly civic life carrying on in the background.

He can’t resist the Bauhaus-style geometries of a devastated stairwell, and he continues to use posters and advertising as the layered wallpapers of city life, the changing times graphically evident from a hammer and sickle painted onto a facade.

Scheidegger’s skills as a portraitist are tested and developed in pictures of children, many of them in Italy and Switzerland where he found his ideal subject – the circus. The late 1940s were busy years for Scheidegger, who, following his periods of military service, worked as an assistant to the artist and architect Max Bill, and also for the photographer Werner Bischof.

Both were key influences on Scheidegger, who drew on Bischof’s poetic but nevertheless unsentimental depictions of postwar Europe and shared his fondness for unusual angles, and the incidental poignancy and interest that could be found in posters and commercial imagery.

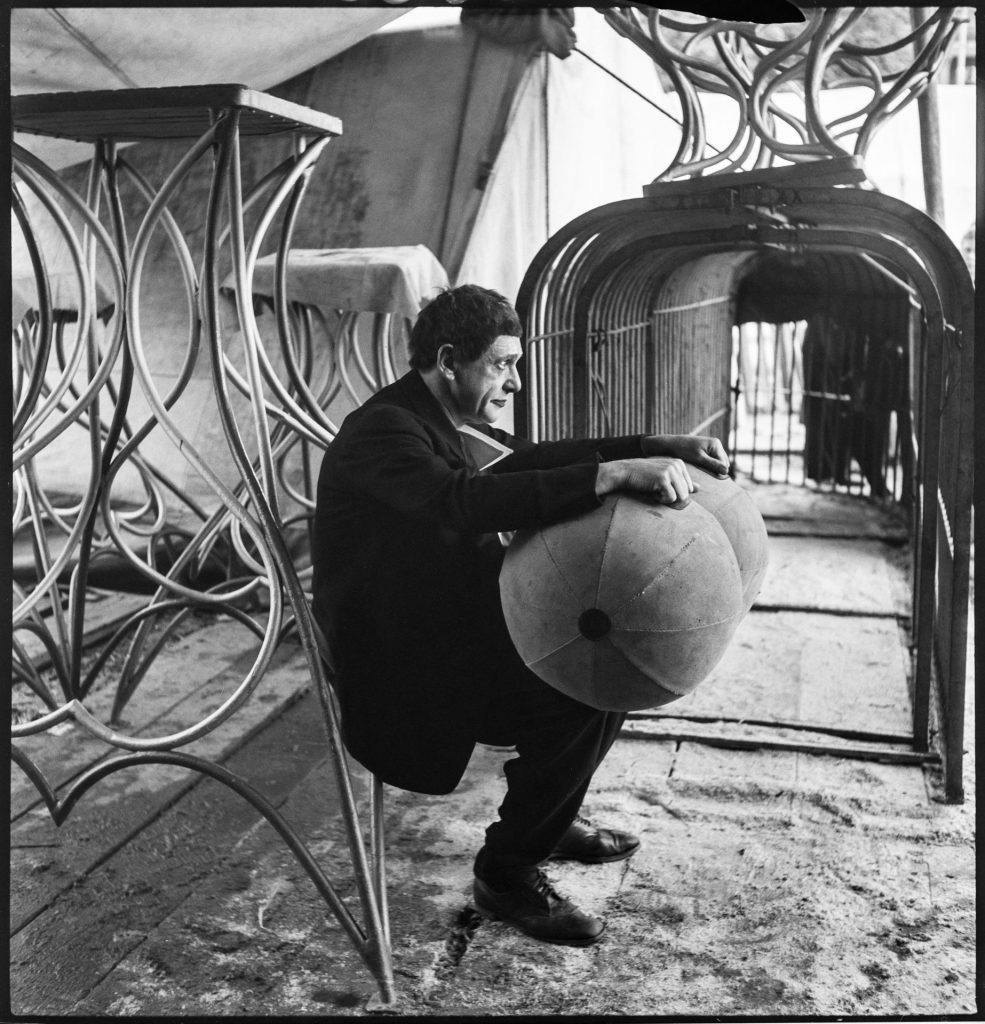

The surreal but humane humour in photographs like Swing Boats, 1950, and Artistes and horse dummies at Zirkus Knie, c.1949, owes much to Bischof, and it is in these works, culminating in the Clown awaiting his cue at Zirkus Knie, c.1949, that Scheidegger honed his knack of using a person’s surroundings and attributes to project and elucidate their character.

That these pictures from the 1940s and early 1950s largely disappeared from view was an entirely deliberate decision by Scheidegger, marking the end of his nascent career as a photojournalist in 1954, following the deaths of two of his closest friends.

Scheidegger had moved to Paris in 1949 to take a job initially offered to Max Bill, designing exhibitions to promote the postwar reconstruction work of the Marshall Plan, or European Recovery Project (ERP) as it was officially called.

In Paris he began working for the French art magazine XXe Siècle, and for the Aimé Maeght Gallery, work that brought him into contact with many of the artists who would feature in his later work, including Giacometti, Miró and Georges Vantongerloo.

The move to Paris coincided with the founding of celebrated photo agency Magnum, formed in the aftermath of the second world war by veteran photojournalists David “Chim” Seymour, Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson and George Rodger. With its connotations of guns and champagne, glamour and danger were written into its name, and Scheidegger, having been introduced to Capa and Cartier-Bresson by Bischof, soon found himself on assignment in the Far East, Asia and the Middle East, for such noteworthy titles as Life, Picture Post and Stern.

It must have been a thrilling few years, his trips away punctuated by spells at home in Paris where he continued photographing his artist friends.

But then everything changed: on May 16, 1954, Bischof died in a car crash in the Peruvian Andes. Nine days later, Capa was killed by a landmine in Vietnam.

The news of both deaths arrived in Paris simultaneously and, writes Bezzola, “so devastated was Scheidegger by these two deaths that he was barely able to speak of them at all”.

There was added torment for Scheidegger: the Vietnam assignment had originally been his, but when only he was able to get a visa in time to cover a state visit in Egypt, Capa took his place, “despite,” writes Bezzola, “having previously sworn that he was finished with war”.

The deaths of his colleague and mentor had a profound effect on Scheidegger, who could no longer bear to work as a photojournalist, archiving his work from 1945 to 1955, and taking a job as a lecturer in visual design.

So began an extraordinarily diverse period in his career, in which most of the artist portraits were commissioned, by magazines and books, and eventually his own publishing house.

He embraced modern media, producing work for newspapers and Swiss television, for whom he began making artist documentaries in the 1960s, notably on Giacometti in 1966.

In bringing together the full scope of Scheidegger’s career, the exhibition not only uncovers the outstanding early works of this great figure from photography’s golden age, but elucidates the later, more familiar artists’ portraits. Tragedy changed the course of his career, but perhaps it freed him, too.

He was never a pure photographer, says Bezzola: “He was always a publisher, author, graphic artist, gallerist, film-maker, exhibition-maker, and catalogue designer who just happened to be adept with a camera.”

Eye to Eye: Giacometti, Dalí, Miró, Ernst, Chagall – Homage to Ernst Scheidegger is at Museo d’arte della Svizzera italiana, Lugano until July 21