The Day After (1983) was a fictional TV film that showed what nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union would look like. Its first broadcast saw 100 million Americans tune in, including then-US president Ronald Reagan.

It would be wrong to say that the show, which starred the former actor’s contemporary, Jason Robards, immediately turned the hawkish Reagan into a badge-wearing CND member – indeed, less than a year later, a leaked recording from a radio studio found him joking, “My fellow Americans, I’m pleased to tell you today that I’ve signed legislation that will outlaw Russia for ever. We begin bombing in five minutes.”

Yet The Day After did have a profound impact on the seasoned cold warrior. “It’s left me greatly depressed,” Reagan wrote in his diary. “We [must] do all we can to have a deterrent & to see there is never a nuclear war.”

When Reagan wrote those words, there were roughly 60,000 nuclear weapons locked and loaded between the two cold war superpowers. Today, the global figure is less than 12,500. Yet when the American investigative journalist and author Annie Jacobsen researched the subject for a new book, what she found terrified her. The stockpile of warheads may have diminished, but there are more nuclear powers than before.

And when the potential to launch is in the hands of the likes of Vladimir Putin – seen wielding his nuclear briefcase at Russia’s recent Victory Day celebrations – plus Kim Jong Un, Xi Jinping, Benjamin Netanyahu and perhaps soon Donald Trump again, one can be forgiven for feeling as depressed as Reagan did in 1983. The prospect of nuclear war – perhaps even the accidental kind depicted by Stanley Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove in 1964, is still alarmingly real.

In June 1983, the president ordered a simulated war game, code-named Proud Prophet, to predict what a post-nuclear world could look like. It took place at the National War College near the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia. In Nuclear War: A Scenario, Jacobsen writes: “The goal of Proud Prophet was to demonstrate what happens when diplomacy [and] deterrence fails.”

She is an expert on all matters pertaining to war, weapons, security, intelligence, and government secrets. Her previous books include Surprise, Kill, Vanish (2019), Operation Paperclip (2014) and Area 51 (2011), which was shortlisted for the Pulitzer Prize.

Jacobsen’s latest book includes interviews with presidential advisers, cabinet members, nuclear weapons engineers and intelligence analysts. All agree that nuclear war is insane and absurd. Primarily, this is because nobody wins.

Proud Prophet – classified by the US Department of Defense until 2012 – predicted that following a major nuclear conflict, large parts of the northern hemisphere would be left uninhabitable for decades, with half a billion human beings killed in the initial nuclear exchanges. This grim forecast, as well as the knowledge that the creaking Soviet economy could no longer sustain the aggressive pace of the arms race, led Reagan to reach out to his Soviet counterpart.

The Reykjavík Summit, held on October 11-12, 1986, was his second meeting with Mikhail Gorbachev. The world’s nuclear weapons stockpile had by then ratcheted up to over 70,000. By July 1991, Reagan’s successor, George HW Bush, had signed the Start treaty with Gorbachev, both countries agreeing to reduce their deployed nuclear warheads to below 6,000 over the following three decades.

“When the cold war ended, most people saw the nuclear threat as non-existent,” Jacobsen explains from her home in Los Angeles. “And yet, [not long ago] the president of the United States was saying nuclear Armageddon is now a bigger threat than at any time since the Cuban missile crisis of 1962.”

Jacobsen is referring to a speech Joe Biden gave in October 2022 about the prospect of nuclear weapons being used for the first time since August 1945. In March, the New York Times, under the headline “Biden’s Armageddon Moment”, reported that the president made those comments based on solid CIA intelligence. This revealed that, after the world’s furious reaction to the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Russian military had several internal conversations about seriously reaching into their nuclear arsenal.

And last week, Putin’s defence ministry announced plans for tactical nuclear weapons manoeuvres near the Ukrainian border in “the near future” – the first such exercises since Russia’s invasion in 2022.

Jacobsen knows just how easily a nuclear threat can escalate. She cites an incident that occurred in November 2022 in Przewodów, southern Poland, when a stray Ukrainian missile killed two people. Initial fears that it was a Russian weapon caused the Poles to explore invoking Article 4 of Nato’s treaty, which allows members to discuss whether the security of any of them is under threat.

If the answer is yes, the next step is invoking Article 5, whereby all Nato members promise to take any action necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic Alliance.

Thirty-six hours after the Przewodów missile incident, General Mark A Milley, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (the principal military adviser to the US president), admitted that he had been unable to communicate with his Russian counterpart during the crisis.

“There is no magical red telephone that allows the leaders of the United States and Russia to communicate with one another in a time of a [nuclear] crisis, it’s pure fantasy,” says Jacobsen. “The United States and Russia need to be able to communicate in seconds and minutes, not hours and days, because all it takes is one technical failure and nuclear war could begin, which is the pathway to Armageddon.”

But what happens when technology fails? Jacobsen cites research carried out by Theodore Postol, a professor of science and national security policy at MIT who previously worked at the Pentagon. In a 2015 Senate briefing called Accidental Nuclear War between Russia and the United States, Postol said: “Russia’s fragile early-warning system poses one of the greatest dangers of nuclear use [that is] currently facing the US.”

Jacobsen explains: “Postol told me that, right now, a Russian satellite could mistake sunlight, or clouds, as an exhaust coming out of the back of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ISBM). Meaning Russians could misinterpret a nuclear launch, and in response could potentially launch nuclear weapons in what they think would be a counterattack.”

Today, nine countries possess nuclear weapons: the US, Russia, France, China, the UK, Pakistan, India, Israel, and North Korea. “Any nation with nuclear weapons is just as much a threat as any other nation with nuclear weapons,” says Jacobsen.

Russia is officially known to have 1,674 nuclear weapons on ready-for-launch status, but is thought to be able to call on many more – a total of 5,000-plus. The US has a similar number. China has 410. Pakistan and India each have around 160, North Korea 50.

Yet “the US Department of Defense predicts that in the next 10 years, China may have 1,500 nuclear weapons”, says Jacobsen, “so the arsenals are building back up.”

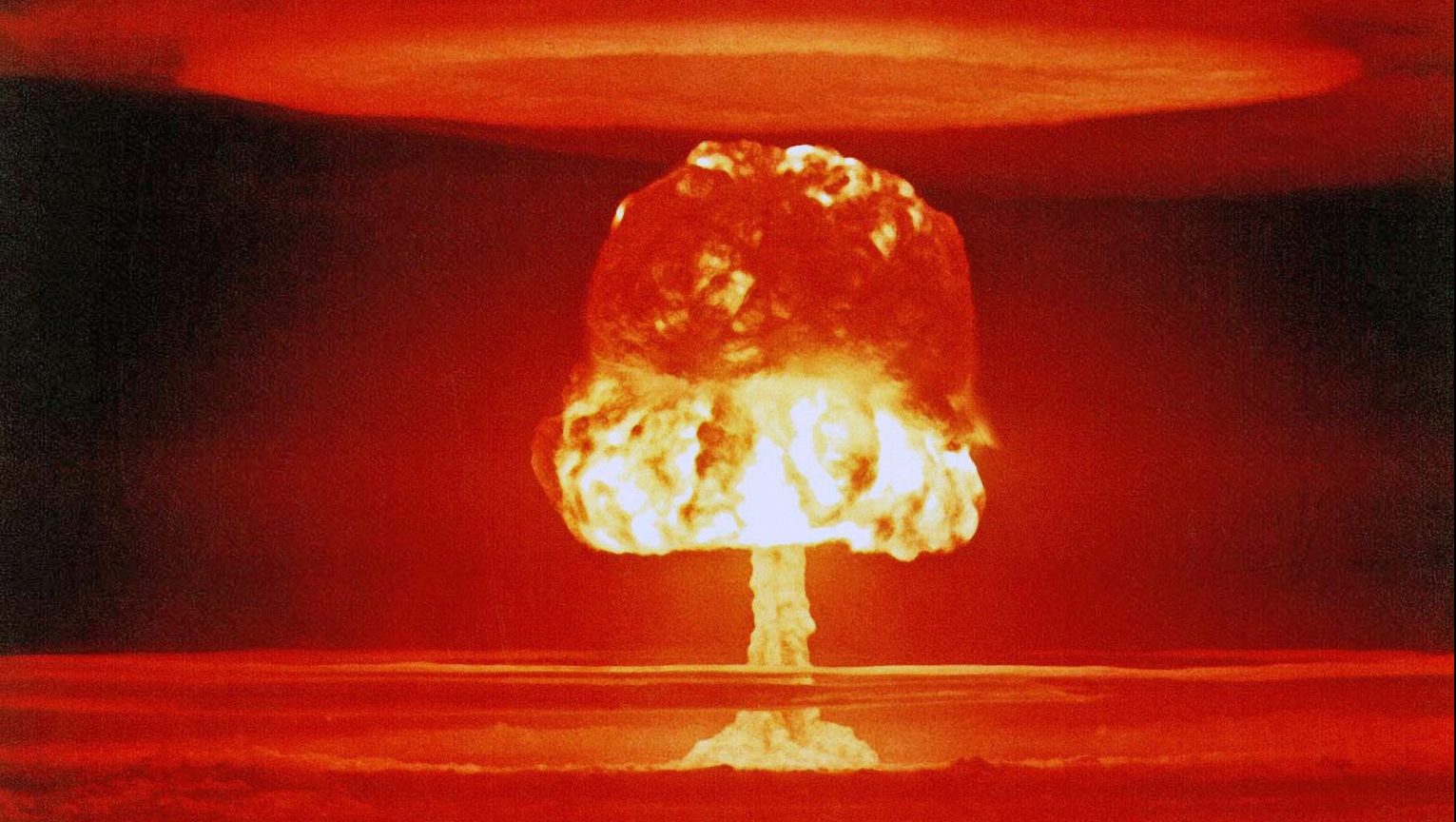

Jacobsen’s book is aptly timed, following the seven Oscars scooped by Oppenheimer at the 2024 Academy Awards. The film documented the life of Robert Oppenheimer, the American theoretical physicist who oversaw the Manhattan Project that created the world’s first-ever atomic bomb, which was dropped on Hiroshima in August 1945, killing more than 80,000 people in a single strike.

Jacobsen notes that a year later, the American nuclear stockpile had grown – but to just nine atomic bombs. By 1960, the figure stood at 18,638.

In December of that year, a group of American military officials convened at US Strategic Command, a nuclear deterrence centre at Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska, to share a secret plan (still in a theoretical stage) to hit Moscow in a pre-emptive first nuclear strike.

Known as the Single Integrated Operational Plan for General Nuclear War (Siop), it calculated that 275 million people would be killed in the first hour, and that at least 325 million more people would die from radioactive fallout over the next six months. Since the world’s population then stood at three billion, the 600 million dead would have accounted for one-fifth of the planet.

In his book, Doomsday Delayed (2008), John Rubel, who in 1960 was a director of research and engineering for the US Department of Defense, confessed he was privy to this US plan for nuclear war. It reminded him, he wrote, of a conference held in the Berlin suburb of Wannsee, in January 1942, where several mid-ranking Nazi officials devised a plot to exterminate all of Europe’s Jews.

Much of the declassified data Jacobsen cites in Nuclear War: A Scenario comes from the Los Alamos National Laboratory Archives. “At my request, they declassified the original story of the football,” she explains. “This is a hand-held, aluminium and leather bag that the president of the United States carries at all times.”

“The football has been shrouded in mystery for a very long time,” says Jacobsen. “It essentially allows the president of the United States to confirm his identity, as he connects to the National Military Command Center (NMCC), which is the nuclear bunker beneath the Pentagon. To launch these nuclear weapons, the president doesn’t need approval from anyone else.”

Inside the football are papers said to be the most highly classified set of documents in the US government. Called Presidential Emergency Action Documents (Peads), they are executive orders and messages that can be put into effect the moment an emergency nuclear scenario arrives.

These documents are informally known as the Black Book, Jacobsen explains. “This is a nuclear war plan that is designed down to a menu-like set of options for the president to choose from (in this insane timeframe), which is thought to be approximately six minutes, to make a decision to counterattack.”

Siop has never been formally activated. But a similar, still-classified plan exists. “Over the years, its name has changed,” Jacobsen explains. Today, it’s [believed] to be called the Operational Plan, or OPLAN 8010-12…directed against four identified adversaries of the United States – Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran.”

Nuclear War: A Scenario concludes with evidence published in the Nature Food academic journal last year. The scientific paper claimed five billion could die from a nuclear war between the US and Russia. “After nuclear winter, nothing new grows in the cold and the dark,” Jacobsen explains.

Large areas of the planet would drop in temperature. The bread baskets of the world (places like Ukraine and Ohio in the US) would be permanently under deep snow, putting an end to agriculture. Meanwhile, soot thrown into the air from a nuclear attack would block out 70% of sunlight.

“Those who survive the initial nuclear fireballs would face starvation,” Jacobsen concludes. “It really makes you think of that haunting quote by Nikita Khrushchev: ‘The survivors would envy the dead’.”

Nuclear War: A Scenario by Annie Jacobsen is published by Torva at £16.99