Preserved as a silent newsreel, Sarah Bernhardt’s funeral procession through Paris on March 28 1923 remains a magnificent if perplexing spectacle one century on. For half a mile, carriages laden with floral tributes, accompanied by splendidly uniformed official mourners, attending dignitaries and girls carrying palm leaves, made their way through the largest crowds seen in Paris since the armistice.

The honours bestowed on the “Divine Sarah” (1844-1923) match, and perhaps exceed, the pomp of any other state occasion – and yet all this splendour and ceremony was for an actor who predated the golden age of Hollywood by decades, and who, by the time of her death at the age of 79, was a relic of the distant past.

By 1923, Bernhardt’s famed performances of Shakespeare, Racine and Dumas – said to have regularly brought her to near collapse, and even to spit blood – were old hat, her legendary “golden voice” made irrelevant by silent movies. Still, that she continued to make hugely profitable films into old age is proof of more than a loyal following: Sarah Bernhardt’s unique celebrity was rooted deeper than her acting.

To mark 100 years since the death of the woman Jean Cocteau called a “sacred monster”, a lavishly staged exhibition in Paris presents a fascinating treasure trove of more than 400 objects associated with the grande dame of French theatre. The Petit Palais was built in 1900 for the Exposition Universelle, and provides the perfect setting for photographs, paintings, sculptures, costumes, furniture, archival footage and recordings, many of which belong to the museum’s personal collection.

Organised thematically, in galleries that evoke the interiors of the time, And the Woman Created the Star explores the fascinating story of a woman who was simultaneously emblematic of fin-de-siècle Paris, and completely ahead of her time. She was an enthusiastic trouser-wearer, a businesswoman, an actor who tackled famous male roles, a sculptor, and an unmarried mother; she occasionally slept in a coffin, and her prodigious sexual appetite was satisfied with numerous male partners, and a long-standing romantic relationship with the painter Louise Abbéma. Bernhardt’s experimental attitude to gender in the theatre, and especially her challenges to female oppression, remain depressingly pertinent today.

Bernhardt’s beginnings were not propitious: one of the first exhibits at the Petit Palais is a Paris police record, beautifully lettered in copperplate, registering her as a courtesan, a profession into which she followed her mother and aunt.

Prostitution was no doubt training of a sort, even if for a very particular sort of theatre, but Felix Nadar’s portraits of her as a strikingly beautiful teenager in 1859 reveal a natural presence that remained largely unchanged throughout her life. The life of a courtesan, as high-class prostitutes were politely called, was conducted in the most influential circles, and so it was that the Duc de Morny, half-brother of Napoleon III, encouraged her to enter the theatre, and sponsored her studies at the Conservatoire where she remained for two years, before joining the Comédie-Française.

Falling pregnant as an unmarried 20-year-old was one of various presumably life-changing calamities suffered by Bernhardt, who later lost a leg, and endured antisemitic barbs and caricatures in the press. All are mentioned so fleetingly that they could be missed altogether, and the woman behind the legend is frustratingly elusive.

Still, the tone of the exhibition is less reverential than it might be, and cuts through the bombastic exuberance typified by the English writer Maurice Baring, (most definitely a fan), in a book published 10 years after Bernhardt’s death. He describes her life as “a whirlwind of dates, titles and gleaming swords, fireworks, poets and prose-writers, men of genius and clever men, garlands, smiles, prayers, and tears. A great clamour arises from it: applause, sobs, whistling trains, steamers screaming in the fog; a kaleidoscope of all countries; a babel of all tongues; shouts of enthusiasm, ejaculations of worship, cries of passion.”

On this evidence, perhaps it’s no surprise that in the end, she was too big a character for the venerable Comédie-Française, founded in 1680 and reputedly the longest-running theatre company in the world. Feeling underused and bored, her relationship with the company ended in 1880 when a major flop, L’Aventurière by Émile Augier, prompted her resignation. Madame Révolte, as the press liked to call her, shared a copy of her spicily worded resignation letter with them: “This is my first failure at the Comédie-Française.” she wrote.

“It will be the last.”

She understood the benefits of good PR, but she was a formidable businesswoman, who capitalised on the power of her name and image in advertisements for biscuits, sardines, face powder and absinthe. She was fascinating to artists, and her portrait appeared regularly in the annual French state art exhibition, the Salon. She achieved Art Nouveau perfection in theatre posters designed by Alfons Mucha, and was caricatured (sometimes quite cruelly) in satirical magazines.

So confident was she in her ability to draw crowds that, during the international tours that dominated the middle years of her career, her own marquee formed part of her colossal entourage, which in the USA travelled by a dedicated train, fitted out as “a palace on wheels”. In the event that she and a local theatre director experienced “artistic differences”, she could simply transfer to her own temporary venue, and perform on her own terms.

In one particularly magnificent photograph, a formidable-looking Bernhardt poses in front of the marquee in Dallas: more astonishing is that the previous year an accident on stage had damaged her knee, an injury so severe that it would eventually lead to the amputation of her leg in 1914 (though even that did not end her career).

And yet she was not entirely a prima donna: during the siege of Paris in 1870, she set up a hospital at the Théâtre de l’Odéon, and following the amputation of her leg in 1915, she joined other actors in entertaining troops, before undertaking an 18-month tour of the USA in 1916 to raise awareness of the fate of Europe.

Perhaps because she felt inadequately stretched by her acting roles that during the 1870s she developed a parallel interest in painting and particularly sculpture. Though often treated as a hobby more than a serious pursuit in accounts of her life, she was sufficiently competent, and serious-minded that she regularly exhibited at the Paris Salon, and in 1876 submitted Après la Tempête, an ambitious, secular reimagining of the grief-stricken Virgin holding the lifeless body of Christ.

Examples of her own, rather romantically gothic work, as well as the paintings and sculptures she inspired, are displayed in a gallery that suggests Bernhardt’s magnificent studio-cum-reception room in her mansion in the Plaine Monceau. A watercolour of her “atelier” shows an easel placed in the middle of an opulently furnished room, its high ceilings and full-length windows letting light and air into a space embellished with rich fabrics and wallpaper, plants and art from the Far East that, writes co-curator Cécilie Champy-Vinas, “gave free expression to her creativity and her exuberance.” The fashionable address in the Rue Fortuny was a fitting backdrop for Bernhardt’s bohemian glamour, and put her in the midst of a community of wealthy, well-connected artists and patrons.

Among her artist friends were the Belgian painter Alfred Stevens, the symbolist Gustave Doré, and Jules Bastien-Lepage, a painter best known for idealised scenes of rural life, but moved nevertheless to produce one of her more famous portraits. She had an affair with Doré, who admired her artistic efforts, and with whom she first travelled to Brittany, where she would eventually make a holiday home on the remote island of Belle- Île. Belle-Île inspired some of her best sculptures, the forms of fish and seaweed and other marine flora and fauna rendered in patinated bronze.

Bernhardt’s most steadfast connections were with Georges Clairin, and Louise Abbéma, with whom she formed a longstanding romantic attachment, expressed in numerous, reciprocal portraits, including Abbéma’s painting of the pair on the boating lake of the Bois de Boulogne in 1883.

Clairin’s portrait of Bernhardt at the 1876 Salon, to which Abbéma also submitted a portrait, has become one of the best-known images of the actor, her virginal white dress offset by her languorous pose and opulently furnished surroundings. Bernhardt’s sculpted portrait bust of Clairin is nearby, a well-placed tribute to their lifelong dialogue in art and friendship.

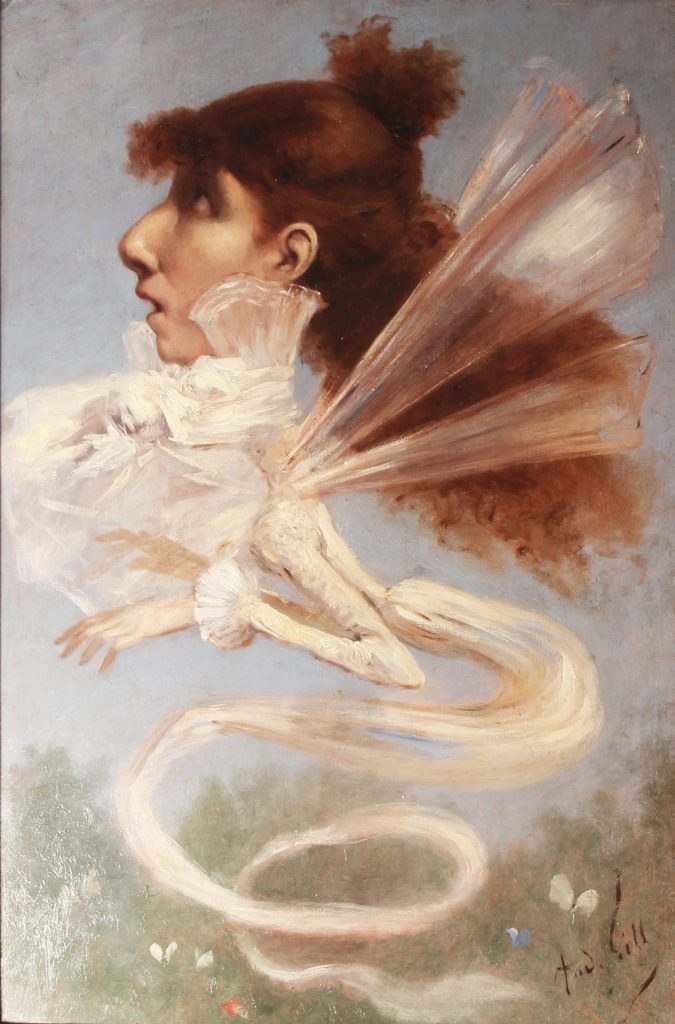

While all unmistakably her, the many images of Bernhardt, by as many different artists and photographers, are endlessly varied, suggesting the chameleon-like skills that made her a great actress. Sometimes she appears in a great role, as Joan of Arc, or Cleopatra, but even out of character she presents, or lends herself to, multiple versions of herself. Achille Mélandri photographs her as an artist, George Rochegrosse immerses her in exotic, Orientalising fantasies, and Georges Clairin presents her as a wraithlike, supernatural being, awaiting the summons of a new role.

The many surviving clothes and costumes are a necessary reminder that Bernhardt was very much flesh and blood. But though she was considered unusually tall in her time, her tiny shoes and corsets confirm her physical frailty, and obsession with maintaining extreme thinness. Certain costumes are strikingly familiar, the design for Cleopatra surely the inspiration for Elizabeth Taylor’s costume in her definitive 1963 performance opposite Richard Burton.

Alexandre Dumas, whose La Dame aux Camélias was the most successful role of Bernhardt’s career, described her as having “the head of a virgin and the body of a broomstick”, a physique that presumably made her ideally suited to playing adolescent boys and young men, which she did from early on in her career, in the travesti roles that were a staple of French theatre. In travesti, men’s roles were played by women, and vice versa, and unlike the “breeches” roles common in English theatre, where the true gender of the actor is eventually revealed as part of the plot, in France, the disguise remained.

As Bernhardt got older, a lack of demanding female roles led her to take on more male roles, and by the turn of the century, she had injected the travesti category with a new gravitas. Inevitably, perhaps, Hamlet was the peak on which she set her sights, since, she said: “No feminine role has provided so expansive an area for the investigation of human emotions and suffering as had Hamlet.”

Today, Hamlet is not only played fairly regularly by female actors, including Cush Jumbo, Maxine Peake and Frances de la Tour, but has also been interpreted as a female, rather than a male role. And though Sarah Bernhardt was not the first woman to take the role – the American actor Charlotte Cushman played Hamlet, Shylock, Lear and Romeo decades earlier – Bernhardt made a sufficiently solid case for putting a woman in the role of a man, that a male role was written for her. L’Aiglon, the story of the ill-fated son of Napoleon, was made into an interminable six-act play for Bernhardt and her new, eponymous theatre by Edmond Rostand. She explained:

“A boy of 20 cannot understand the philosophy of Hamlet, nor the poetic enthusiasm of L’Aiglon, and without understanding there is no delineation of character. There are no young men of that age capable of playing these parts; consequently, an older man essays the role. He does not look the boy, nor has he the ready adaptability of the woman, who can combine the light carriage of youth with the mature thought of the man. The woman more readily looks the part, yet has the maturity of mind to grasp it.”

Presumably referring to her waifish, pageboy appearance, the author Maurice Baring described her as “dressed and got up like the pictures of young Raphael”, and described the rapturous applause that greeted her performance as specifically French in its enthusiasm and receptiveness: “Such things in my experience do not happen in England: except at football matches and fights.”

Still, her Hamlet did not please everyone, and the reviews were varied. One biographer, Gerda Taranow, comments that most Anglo-Saxon audiences found a female Hamlet so disconcerting as to “blur critical vision”, with Max Beerbohm unable to take it seriously, and describing Bernhardt as a “très grande dame” throughout.

Some of the most brutal criticisms of Bernhardt came from George Bernard Shaw, who, arch-realist that he was, was appalled by her feverishly histrionic style, demonstrated in the exhibition in snippets of film footage, and a recording of the famous golden voice. Oscar Wilde is said to have strewn lilies at Bernhardt’s feet when she arrived in England in May 1879, but by the time Shaw was regularly reviewing her performances a decade or so later, she was, in his view, “past her prime”, and reliant on “paint and cleverness.” He was quite often vicious in his criticism of her, and even in a tribute written after her death in 1923, he wrote that the “famous voix d’or was produced by intoning like an effeminate Oxford curate.”

Certainly, by then her time had passed: and yet the crowds that followed her coffin, and even this exhibition with its many glittering tributes to the great star, insist otherwise. The enigma of the “Divine Sarah” remains intact.

Sarah Bernhardt: And the Woman Created the Star, Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris until 27 August. Petitpalais.paris.fr