Sam Peckinpah made westerns. With a filmography featuring The Wild Bunch, Ride the High Country, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, The Ballad of Cable Hogue and Junior Bonner, he had as good a claim as any to be the finest director of horse operas this side of John Ford.

Even Peckinpah’s non-western pictures – the brutal, Cornish-set revenge drama Straw Dogs, the brutal Mexico-set revenge drama Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia – aren’t so thematically distinct from his stories of no-good gunslingers and bloody betrayal.

But by the mid-1970s, the box-office failure of Pat Garrett and Alfredo Garcia, together with Sam’s lengthy, ongoing battle with alcoholism and his recent discovery of cocaine, meant our man couldn’t be so picky about the movies he made. So it was that Peckinpah closed out his career with a pair of so-so espionage thrillers – The Killer Elite and The Osterman Weekend – and the epic road comedy Convoy which, in keeping with the perversity that was the one constant of Peckinpah’s career, didn’t let its immense shortcomings prevent it from becoming his biggest box-office hit.

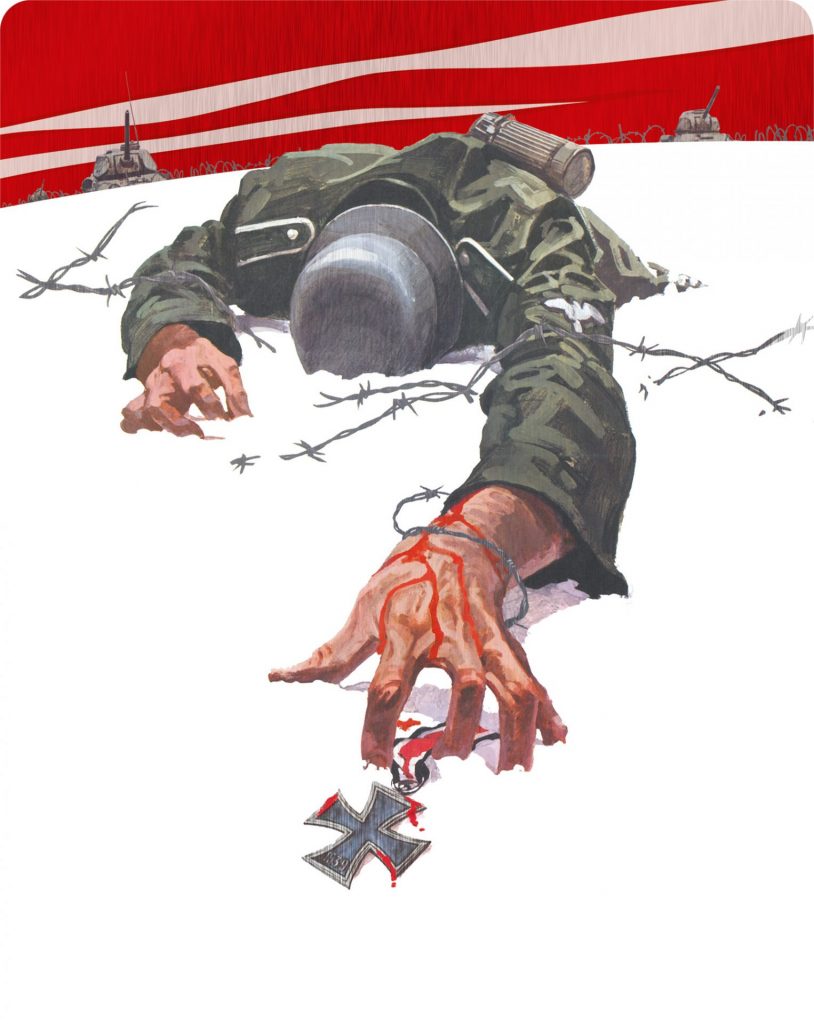

Yet among these lesser works, Peckinpah found time to make a war movie that is the equal of even the very best of his westerns. The film was Cross of Iron (1977), and its brilliance is all the more remarkable for its having been made in a state of chaos that almost resembled warfare itself.

Predominantly shot in what was then Yugoslavia, Cross of Iron is the story of Sergeant Steiner (Peckinpah regular James Coburn), a German officer so at odds with the Nazis and their cause that he dares to speak with an American accent. Steiner is serving in the Taman Peninsula on the Eastern Front and, while it might only be 1943, he’s under no illusion that the Soviet Union is bound to win the day.

Into this desperate situation comes Captain Stransky (Maximilian Schell, who won the Best Actor Oscar for Judgment at Nuremberg), a Prussian blueblood who has asked to be posted to the eastern front as he believes that the fighting there will increase his chances of receiving the Iron Cross. A man obsessed with personal glory, serving alongside a man whose ambitions are simply to get through another day, Stransky and Steiner are so at odds that they might as well be fighting on opposite sides.

It’s this rivalry – together with the impotence of the German high command (represented by James Mason’s weary Colonel Brandt and David Warner’s dysentery-ridden Captain Kiesel) – that lends colour to a picture famed for its battle footage. Indeed, Steven Spielberg so admired Peckinpah’s shot selection and editing strategies that he borrowed both for the opening and closing massacres of Saving Private Ryan.

Influential as it is today, Cross of Iron went into production with everything against it. Peckinpah’s stock was as low as it had ever been and producer Wolf C Hartwig, with a background in soft porn, added little to proceedings in the way of respectability or glamour. Out of sorts as he might have been, the ageing, addled director was keen to get the very best out of his cast, as Coburn recalled:

“Sam insisted that we visit Koblenz, where they had a pristine print of Triumph of the Will, Leni Riefenstahl’s film about the [1934] Nuremberg Conference. After watching that, we all understood how these men had fallen under Hitler’s spell. That opening sequence, where you wait 40 minutes for Hitler’s plane to touch down, is amazing. You see those people looking up at the sky, looking like they’re expecting God to arrive. By the time the tri-engine lands and he steps out, you almost feel like cheering!”

Of course, the Führer’s hold upon his men has long since evaporated by Cross of Iron’s opening scenes. As Ian Johnstone remarked when profiling Peckinpah’s film for Neon magazine, this is a film more interested in class than Nazism. There’s little to no discussion of Nazi doctrine (“We are spreading the German culture throughout a desperate world,” says Steiner at his most sarcastic), but the film has a lot to say about the relationship between the aristocracy, who see war almost as a game, and the working man for whom battle is just drudgery in a different uniform.

Speaking of hard slogs, Cross of Iron’s Yugoslavian shoot was a bit like boot camp. Promised no end of military hardware, Peckinpah had to make do with just three Russian tanks, each of which was fighting its own losing battle with rust. The director also had just 300 uniforms to hand, a misfortune that kept the costume department busy 24 hours a day.

Sam being Sam, he didn’t hesitate to complain about the hardships he endured. “I can’t tell you what it’s been like,” Peckinpah explained to a German movie magazine during a set visit. “Delays, halts in shooting, no rushes, no film sometimes. The producer says it’s trouble at the border. I asked him if not paying the crew was due to trouble at the border…”

Diplomacy never having been Peckinpah’s strong suit, it’s important to note that he wasn’t the only one upset with Hartwig and his fellow execs. With the production set to wrap and the director still short of a satisfying conclusion, the producers intervened, much to the chagrin of Coburn.

“Wolf had started to panic and insisted that Sam shoot some silly little scene that [he and the execs had] written,” he remembered. “And Sam started to whine: ‘They’re taking it away from me! They’re taking my movie away from me!’ I said, ‘Get Max[imilian Schell] and let’s get running.”

Scheduled for three days, Cross of Iron‘s compelling final sequence – in which a Russian boy soldier takes pot-shots at an increasingly hysterical Stransky – was filmed in a little over four hours.

Against all the odds, Cross of Iron arrived in European cinemas in February 1977. Well-received on the continent, hopes were high for the film’s chances in the US. Within hours of the picture’s American premiere on May 11, the critics were claiming that the film was but further evidence of how far Peckinpah had fallen. Stories about the director’s on- and off-set behaviour – unable to find any cocaine in the Eastern bloc, he took to drinking 120-proof slivovitz (a plum brandy) by the litre – only cemented the image of “Bloody Sam” as a spent force.

And the end result? Well, Cross of Iron was never likely to do well across the Atlantic. My book The Pocket Essential Sam Peckinpah describes it as “an English-language film made in Yugoslavia by a German porn producer that sympathetically tells the story of World War II from the Nazis’ point of view and suggests that it was the Soviet Union who really won the war.” Why, the only way it could have been any less appetising to US moviegoers was if Cross of Iron came with subtitles.

Thankfully time has been kind to it. Take in any war film today – especially one where tanks play a pivotal role such as David Ayer’s Fury (2014) – and you can be sure the director watched and rewatched Peckinpah’s picture beforehand. Cross of Iron now regularly appears on surveys of great movies in general, and classic combat pictures in particular.

Since he died in 1984, Peckinpah hasn’t been around to hear the many nice things that have been said about his art and his artistry. As David Warner – aka Cross of Iron’s Captain Kiesel – told me, Peckinpah was aware of praise from one particularly influential quarter: “Orson Welles cabled Sam to tell him that Cross of Iron was, if I recall rightly, the greatest anti-war film he’d seen since Lewis Milestone’s All Quiet on the Western Front [1930].

“James Coburn said that he hoped Sam had a good drink or two when or if he heard that. Well, I know that he did, and he did!”

And as for what a 1940s-set movie made in the 1970s has to say about the 2020s, one need look no further than Cross of Iron’s end credit sequence where images of atrocities from before, during and after the second world war appear alongside these lines from Bertolt Brecht:

“Don’t rejoice in his defeat, you men. For though the world stood up and stopped the bastard, the bitch that bore him is in heat again.”

A brand new restoration of Cross of Iron is available on 4K UHD Steelbook, Blu-Ray and DVD now courtesy of STUDIOCANAL.