Photographer Vasilaki Kargopulo’s work so impressed Abdulhamid II, 34th sultan of the Ottoman empire, that he was named Photographe de Sa Majesté Impériale le Sultan. The appointment was a terrific boost to Kargopulo’s business as the owner of Istanbul’s first photography studio.

Kargopulo, who opened his atelier in the Beyoğlu district of Istanbul in 1850, took portraits of the sultan in his pomp, and recorded the fading glory of the royal court as well the bourgeoisie at play, the mosques and the palaces.

His pictures chronicle an era and a style of photography now endued with the patina of time, the romance of black and white that was, to over-simplify, limited to what could be seen through the lens.

How that has changed, as a significant selection of works by Turkish photographers at this year’s Photo London testifies. They reflect a burgeoning Istanbul art scene with galleries such as Dirimart and Galeri Nev achieving international recognition and given even greater credibility with the reopening last year of the vast if controversial Istanbul Modern.

No cosy portrayals of bourgeois Istanbul from these photographers, but Kargopulo would no doubt admire the creativity on show, perhaps even appreciate the challenges – often subversive – to what constitutes a photograph. He might be pleasantly surprised to find that they have one thing in common – most of the galleries hail from the same alleys of the old district of Beyoğlu where he and many other contemporaries began their careers.

What then to make of the work of 44-year-old Sergen Şehitoğlu, whose gallery Sanatorium is on one of the district’s now fashionable streets? For his contribution to Photo London he did not use a camera.

In his collection Kill Memories, he presents two contrasting sets of work which the gallery boasts “both redefine the boundaries of photography and question the limits of the concept of privacy”.

In one series he follows a young woman on a sex webcam. He looks on as she talks to her anonymous clients, often about trivial matters like her new hairdo, how she’s feeling, thanking admirers for letters and, of course, sharing their sexual fantasies.

Sometimes she puts on an erotic show but we see nothing of that, only unflinching close-ups of her face. With her blonde hair and red lipstick she should embody the part of an onscreen seductress, but she seems rather thoughtful and distracted, almost vulnerable.

She knows what she’s doing and she knows she is in the public gaze, making money as the punters log on and look in, but she does not know about Şehitoğlu, who for two years watched, took screenshots and downloaded them.

Isn’t he invading her privacy with this anonymous eavesdropping? Haven’t the boundaries between private and public become blurred?

“It’s an erotic show, but it’s a relationship between her and the admirers, and what I’m interested in are the interactions between them,” he says. “I called the series Kill Memories because that is her nickname. I wanted to show that you cannot kill your memories. Think about it; you are a young person, say 15 years old, you make something visual but you cannot cancel it. We make a lot of mistakes in our young lives. It could be the end of your life. Do what you will, but don’t take photos like that. It’s too dangerous.”

The companion piece, GSV (Google Street View) has Şehitoğlu, once again, in front of a screen, wandering the world on Google Maps, scouring the hundreds of thousands of images that the Google vehicle is taking.

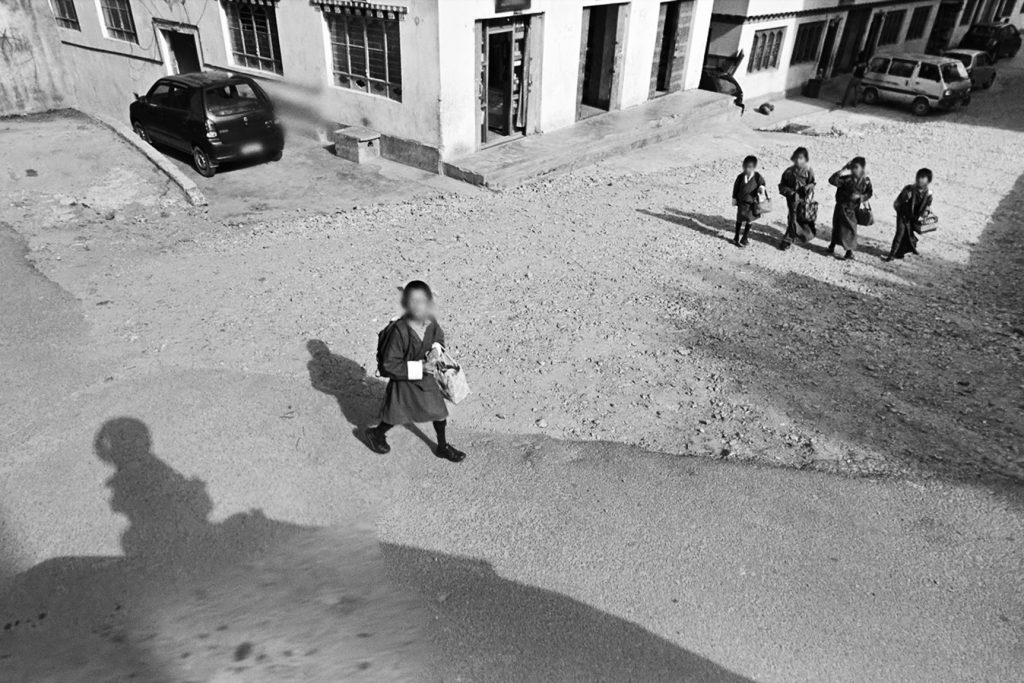

Every download includes the pole on the roof of the car, or rather its shadow on the ground, as its nine “eyes” surveil all around it. We see a man outside a McDonald’s in Chicago, intrigued children in Bhutan, a lone swimmer on a Greek beach, two men on an empty street in South Africa. “It’s like an alien thing,” says Şehitoğlu. “It’s not normal that there are millions of people online but they don’t know they are.”

But is this redefining photography as the publicity suggests? “I think the important thing about art is not just to make but to select. It’s not just that you are a painter or have taken a good photograph, now the idea is about choosing the process to make your body of work.”

If his work reflects the ever-changing role of the photographer from recorder to interpreter, the factual to the subversive, he is not alone. One of the most revolutionary of Turkish photographers was the late Şahin Kaygun (1951-1992) who was rarely satisfied merely to shoot a photograph but rather to create visual stories, often using Polaroids, manipulating the results by scratching the surface, cutting out parts of the subject, colouring over or drawing on it and adding details.

The result is a mix of the dramatic and the eerie; naked women who surge out of dark backgrounds, blurred, pixelated faces framed in black, a shadowy naked woman covered only with daubs of yellow paint, the naked top half of a woman sitting at a table with a doll’s head on a plate.

Kaygun was an inspiration to many of today’s younger Turkish photographers, including Yusuf Sevinçli, who is represented by the same gallery, Galerist, and like Kaygun, produces work which is “rarely related to reality.”

His latest series, Tumult, does give one pause; an unnerving close-up of a woman apparently gagging on an ice cube, a rock hanging above the sea on a rope, a blazing bonfire, a tableau of peacocks, a leap of antelopes (stuffed) which he found in a French museum, a preening crow. Perfectly composed, a full moon is shot through a rainswept window.

What, if anything, is he trying to say with these apparently random images? “Most explanations are boring,” he says. “I like abstractions. I like metaphors. When the audience look at my work I want them to study it and not just skip to the next after a few seconds. The photos should be open to their interpretations.

“The woman and the ice cube was just a chance moment during a theatre group rehearsal which involved huge cubes of ice. The rock was used to hold down a tent on a beach from blowing away in windy weather. I took the moon on the first day of the Covid lockdown but it is not about the pandemic, it’s expressing that particular kind of claustrophobia that we felt.

“They’re all spontaneous. I do not stage the people when I make portraits. I do not change things that are in front of the camera. I do not use fake photography.”

His work, all black and white, is a considerable contrast to the enthusiastic salute to the female form by Nazif Topçuoğlu (Galeri Nev), which he insists is “provocative but not exploitative” yet shows lush, colour-saturated tableaux of young women in various stages of décolletage with more than a hint of Sapphic fun and games. Very obvious, very commercial.

Mert Acar is altogether more uncompromising; nothing voluptuous about his work, nothing posed, no attempts to change or improve what is in front of him and his camera. A lecturer based in Ankara, which in itself makes him something of an outlier from fellow artists in cosmopolitan Istanbul, Acar, 35, admits to being somewhat traditional.

His subject is the wasteland, the empty, characterless locations which have grown up around Ankara, a world of “transitional landscapes” with unfinished motorways leading… where? Of deserted buildings and empty car parks, rows of empty chairs left mysteriously in a field, cracked walls, rusty fences, ugly skylines lined with pylons.

He says: “You can’t see any cultural activity or cultural focal points like in the cities where there is a heritage and history. I figured out that these spaces tell so many things about humanity and how we shape the landscape.”

Some of the most telling photographs use light to contrast with still, empty scenes, whether a house, a deserted petrol station forecourt, a glimpse through trees of a dimly lit front door. Even the glow from a half-opened laptop emphasises the void of a home life. There may be light but it does nothing to illuminate any sense of time or place.

“I wanted to create images where you can hear time is ticking, hear the buzzing lightbulb or hear the crickets or people talking in the distance. I wanted to create some photographs that are like motionless movies.”

He admits to a surprising frustration; that he cannot capture in one moment, in one frame, 100% of what he is trying to express.

“I can never convey the effect I feel with my photographs. I only see a trace of what I am trying to achieve. For this reason, photography is something that always disappoints me.”

No doubt the 19th-century pioneer Kargopulo was just as driven as Acar. Maybe just as disappointed when he was stripped of his title as royal photographer by another sultan.

But isn’t that the artist’s burden? Setbacks, failures, the never quite getting there?

Until you do. Maybe there is some consolation from Henri Cartier-Bresson: “Your first 10,000 photographs are your worst.”

Photo London is at Somerset House on the Strand, London, May 16-19