The English celebrate that he failed, the Scottish celebrate that he had the nerve to try. As one friend tried to explain to an American why her English town would burn a fake scarecrow of Guy Fawkes, a Scot guffawed that no such thing would happen where they were from. Once again, the subject of power imbalance between Westminster and Holyrood managed to rear its head.

For those closely following Scottish politics, this power dynamic is currently playing out through the UK budget and Scotland’s impending devolved one, on December 4. Scotland gets its spending money, like other devolved governments, from the UK government according to the Barnett formula. And now, following the October budget, the Scottish government will announce how they plan to spend their own money.

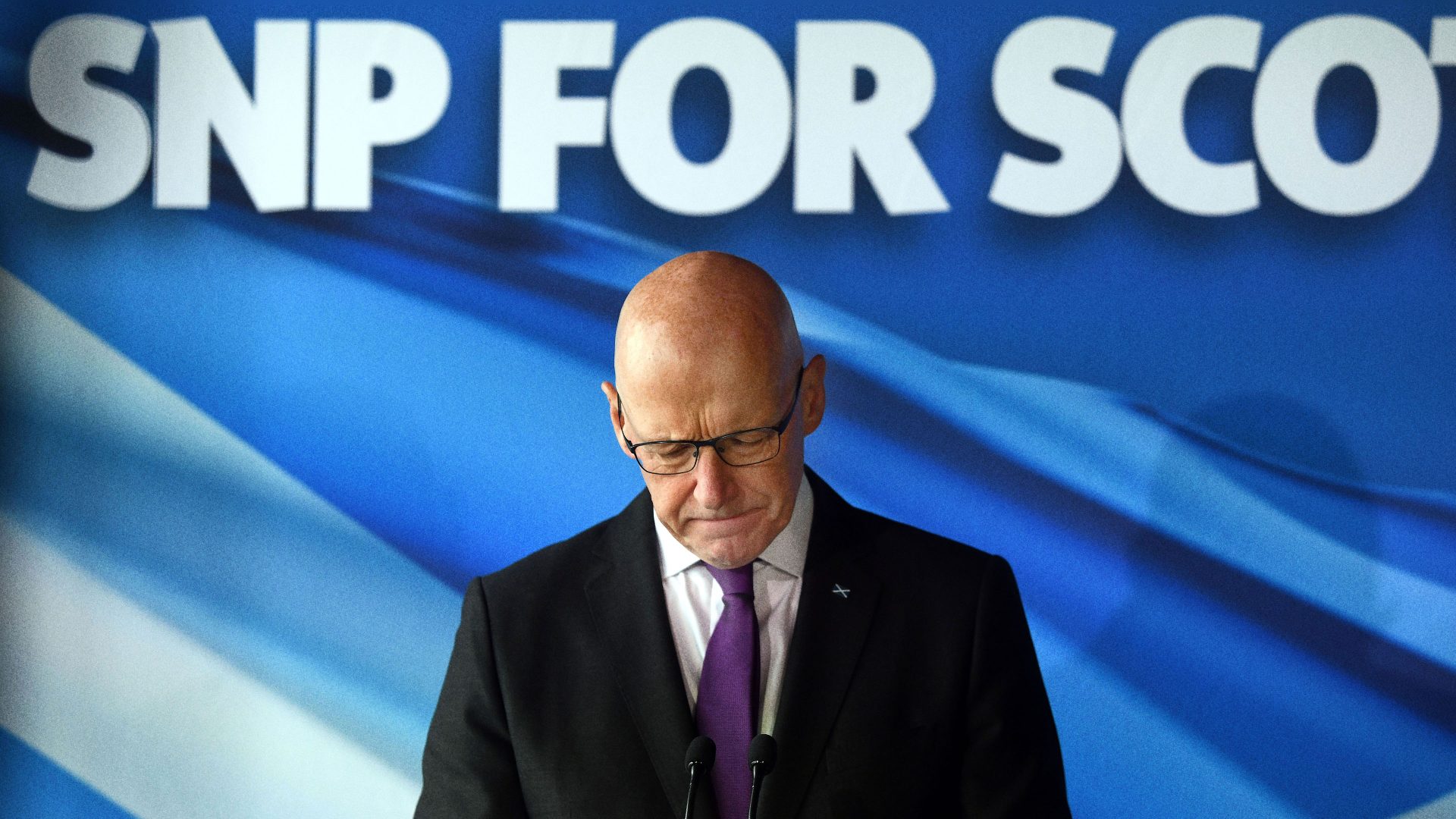

It doesn’t get the media attention of Westminster’s red box. In comparison, the Scottish budget is a blip on the political horizon that even Scottish friends are mainly unperturbed about. But this year it will give an important indication of how Labour can cooperate with John Swinney, the first minister.

After 14 years of the SNP bickering about not receiving enough money, Labour has now stepped up and called Swinney’s bluff. Armed with an extra £3.4bn (as well as a £1.5bn top-up to see out the current 2024-2025 financial year), the SNP can no longer fall back on complaints about Westminster stinginess.

Scotland now has a solid fiscal foundation. Child poverty is lower here than in England or Wales. Scots get free prescriptions, pay no university fees and if you’re under 22, you don’t pay a bus fare.

And yet – NHS waiting times are getting longer, and the Scottish education system is in steep decline. There are a significant number of vacancies for healthcare professionals, with little sign that they’re going to get filled any time soon.

The UK budget has laid out a windfall tax on oil companies that will sting the Scottish economy. Hydrocarbons are Scotland’s largest export, followed by, in the Scottish government’s own words, “drink”. If the SNP want to get serious about Scotland’s future, they’re going to need to invest in alternatives to diversify the economy and ensure Scotland meets its net zero target in 2045. Throwing the Greens out of government wasn’t the best start, but there we are.

Tuition fees are going up in England, and there is a serious question over how long the Scottish government can afford to keep university free. Already, universities are under pressure to accept non-Scottish students to keep up their funding (they only receive £1,500 per Scottish student from the government, compared to almost £30,000 a year for international students).

The result has been frustration from Scottish students that they’re a minority at their own universities. Edinburgh University now has a Scottish Social Mobility Society dedicated to the cause.

Having made grave losses in July and with a leader less than a year into his tenure, Scotland’s reaction to the budget will be a test of Swinney’s premiership and of the party’s ability to stay relevant now there’s a more amenable government in Westminster.

With falling support for independence, the SNP needs to prove its worth. On the issue of another referendum, they’ve reached a stalemate with young people. One pro-

SNP, pro-independence friend wants Scotland to leave the UK in the future – but not now. The country isn’t ready.

It feels necessary to add the distinction of pro-independence alongside being pro-SNP, as young people have started to view the SNP as a protest vote against the Westminster government, but not as a serious political force.

IndyRef 2 feels a long way off. But, despite the Tories now being out, there is still a need for Scottish voices in Westminster. The anger of friends frustrated with the previous government’s incompetence has turned to worry that Scottish issues will get bulldozed by the all-new, powerful Labour machine in Westminster. This is good for the SNP – in fact it might give them a lifeline at the next election. But it means they need to show that they have something to offer for Scotland’s short-term future.

Abigail King is a student writer based in Edinburgh