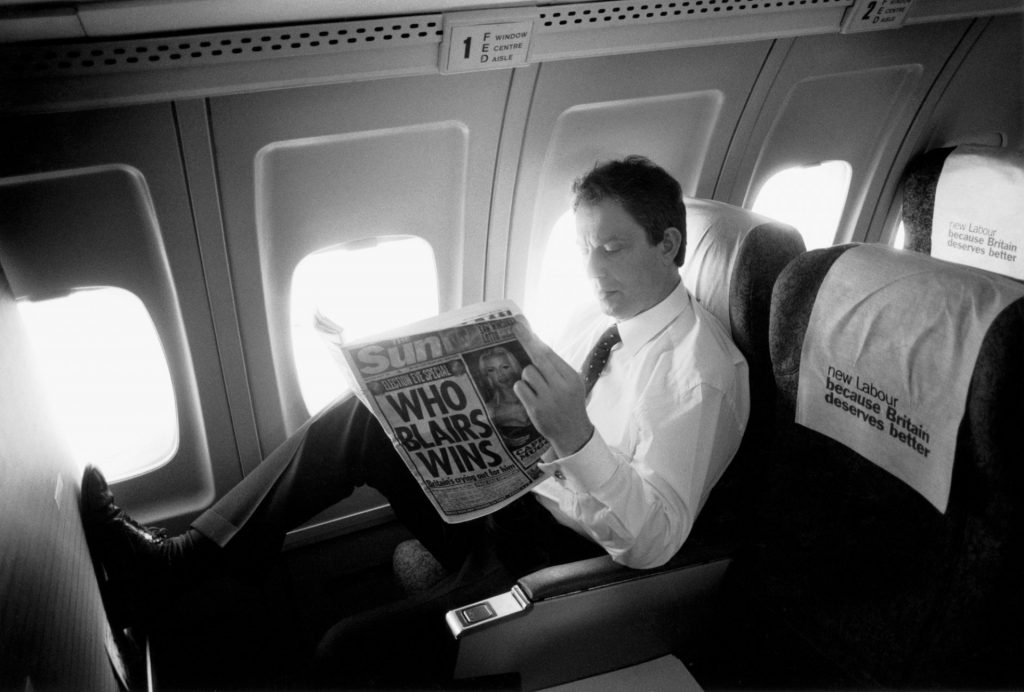

The removal vans have appeared so often in Downing Street over recent years as a succession of Conservative prime ministers have come and gone that it’s easy to forget how a complete change of government usually electrifies politics.

There have only been three of these in half a century: 1979; 1997; and 2010. Each of them sent a jolt through the country, and now we’re all set to experience another one.

Instead of the same old faces being recycled around the cabinet table, this time a Labour prime minister will walk through the door of No 10 with a new team, a different way of governing and a set of ideas that are more radical than they are sometimes portrayed.

The excitement will, however, inevitably be mitigated for a lot of people because Keir Starmer himself spent so much of this election campaign explaining what he wouldn’t do. Taxes on working people will not go up and he won’t borrow more than the economy can afford. There will be no re-entry to the European Union, the Single Market or the Customs Union. Nor will there be substantial shifts in Britain’s position towards wars being fought in Ukraine and Gaza, relations with major powers around the world, or the UK’s possession of nuclear weapons.

All of which is a big change from what Labour might have offered under Jeremy Corbyn – but not much of a change from the Tory government. Indeed, there are already plenty of voices on the left who complain there’s not much to choose between the two main parties these days, while another section of the electorate – not to mention much of the media – will find themselves drawn to the flame of Nigel Farage’s right wing populism.

Starmer’s answer to them all has been, so far, the slightly Orwellian phrase of “stability is change”, together with the promise of a “politics that treads more lightly on all our lives”. This is about both style and substance. “No drama Starmer” wants to “end the chaos” of the preceding Conservative era, which in one year managed to burn through three prime ministers, five chancellors and tens of billions of pounds for the sake of an ideological economic experiment.

He rejects the shrillness of a culture war where this or that marginalised group is paraded across the front page of the Daily Mail as an existential threat to our way of life. He despises the reckless game-playing entitlement that saw Boris Johnson’s Downing Street break lockdown rules, as well as that of Rishi Sunak’s team who apparently raced off the bookies to line their pockets by betting on the date of the election.

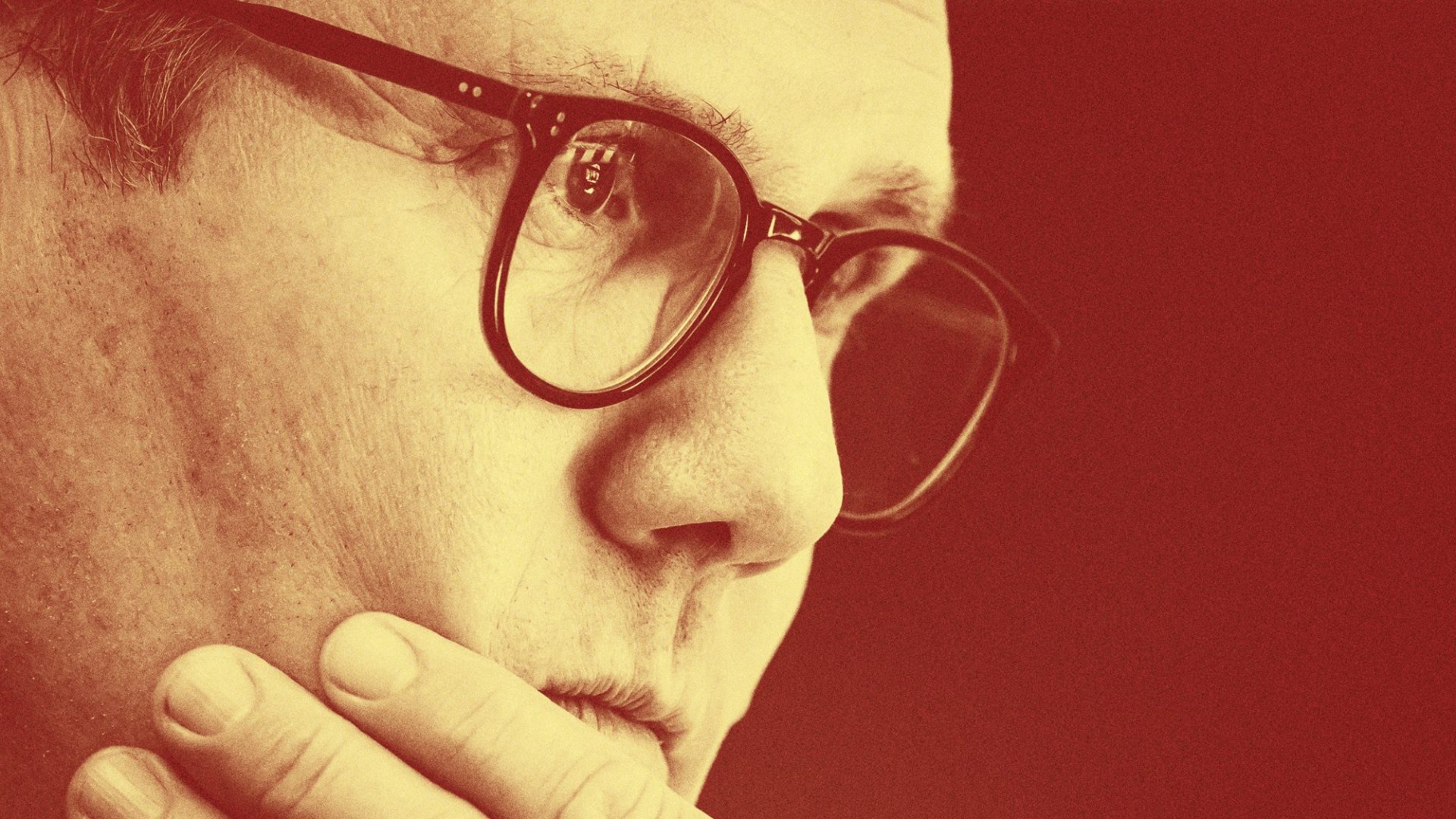

This is a self-consciously serious man who believes politics should be less superficial, not more. Starmer formed his identity as a barrister where he won cases by deploying facts, evidence and dry legal precedents, rather than by setting out his “vision” or explaining to judges that his dad was a toolmaker.

He does not believe that solutions can be found either in three-word slogans or in the constant ejaculations of “charisma” that characterised Johnson’s premiership. In interviews during this campaign, Starmer has been impatient with “pop quiz” questions, or being asked to provide “yes” or “no” answers, which he regards as trivial.

As such, he finds himself in the strange position of being exceptionally successful in his latest profession – he would be only the fourth Labour leader in history to win an election – while also defying expectations of what politicians should be.

When I began writing my biography of Starmer last year, I sought out one of those people whose views are usually only ever offered on condition of anonymity. The verdict was that Starmer had done very well to remove reasons not to vote Labour, but still didn’t deserve to be compared with the previous three Labour winners: Tony Blair in 1997; Harold Wilson in 1964; and Clement Attlee in 1945. “They all encapsulated in a few words, with simplicity and skill, what they wanted to do as prime minister,” this figure told me. “The fear for many of us is that Keir is running out of time to do the same.”

It wasn’t, to be honest, the most startlingly original view. And I wouldn’t bother quoting it now if there hadn’t been a passage in Starmer’s conference speech a few months later which appeared to have been sourced from an almost identical conversation.

“If you think our job in 1997 was to rebuild a crumbling public realm,” he said, “that in 1964 it was to modernise an economy left behind by the pace of technology, in 1945 to build a new Britain out of the trauma of collective sacrifice, then in 2024…” Starmer paused for a second and you could feel the hall tense in anticipation of the next sentence. What would it be this time? “It will have to be all three,” he declared, “all three”.

He is generally irritated by the constant comparisons with previous party leaders, saying: “I don’t need to tattoo someone else’s name on my forehead to know who I am.” And you can imagine him weighing the advice that he needed to be defined by a single purpose “encapsulated in a few words”, before rejecting it.

Although Starmer has faster economic growth as his overarching priority, he won’t budge from his view that the problems faced by Britain, as well as any solutions he will offer, are necessarily complicated and interconnected. And he would also vehemently reject the notion that this means he doesn’t stand for anything. Look again at that passage from his speech. Declaring that he wants to rebuild public services, the economy and the nation itself doesn’t exactly suggest he lacks ambition.

Similarly, the “Five Missions” he set out last year – which include achieving the fastest economic growth in the G7 and net zero electricity by 2030 – should be bold enough for anyone. And, though much of the left continues to complain about his abandonment of the “10 pledges” on which he campaigned for the leadership in 2020, there is plenty of policy – ranging from taking the railways back into public ownership to the promise of a new era of industrial planning and the granting of more workers’ rights – that is radicalism hiding in plain sight.

The missions also reflect how he is driven not so much by a rigid ideology than by a more flexible, hard to codify, but familiar set of values built around patriotism, service and respect. He talks about how each of his missions are “personal to me”. And he can certainly link his own story to the goals of repairing an NHS that was such a feature in a childhood (which was overshadowed by his often very sick mother), of breaking down barriers to opportunity for people like him who came from a working-class background, and of making streets safer from the kind of crime he saw when he was this country’s chief prosecutor.

Although the conventional wisdom in Westminster is that as PM Starmer would swiftly become deeply unpopular, there is also a possibility that his quietly held values will chime louder with voters as time goes on. New polling conducted by More in Common for the UCL Policy Lab showed that a substantial part of the electorate believes that Starmer “respects people like them” and that this was a significant factor in voters switching from Conservative to Labour.

More than anything, Starmer says he wants to be the antidote to the short-termism of recent governments which have provided only “sticking plaster” solutions to chronic problems of under-investment in the economy and public services. He talks of the need for a “decade of national renewal” in which those Five Missions will be both a sorting mechanism, prioritising decisions that might otherwise collapse into a technocratic mess, and a way to project ministers’ reach far beyond Whitehall.

A more valid criticism is that public spending reductions worth up to £20bn, which were baked-in by the Sunak government, increased the need for short-term fixes. There is an active debate about how much of the “tough stuff” Rachel Reeves should do in her first budget as chancellor. It could be that she falls back on the “doctor’s mandate” in which she opens up the books to announce that public spending surgery is urgently required.

But colleagues old enough to have been part of the last Labour government in 1997 will remember how it struggled in its first two years to contain the anger over its refusal to open up the spending taps for pensioners and public sector workers. While there are accountancy tricks and some tax increases that haven’t been ruled out, the room for manoeuvre is limited and potential revenues should be measured in cups rather than buckets.

Starmer and Reeves, however, both insist that the need for tax rises or deep cuts can be avoided if they secure faster-than-expected economic growth with business-friendly measures. Both of them have a capacity for relentlessness which should make critics pause before under-estimating them.

A transition plan led by Starmer’s chief of staff, the former civil servant Sue Gray, has got deep into the detail on planning reforms to get more houses built and unblocking power grids to boost investment in green electricity. None of this will be particularly exciting and much of it will be grindingly difficult to achieve. The focus will be on outcomes – “what works” – rather than single headline-grabbing measures.

These will not always seem transformational and the lines won’t always be clean or inspiring. Often, they will look a little dull. For instance, he has contrasted unworkable but eye-catching Tory schemes to “stop the boats” with armoured jet skis or sending illegal immigrants to Rwanda against Labour’s determinedly dour plan for what he describes as “doing the basics better – the mundane stuff, the bureaucratic stuff” – by improving the speed with which asylum applications are processed.

This is, after all, someone who ran a Whitehall department himself when in charge of the Crown Prosecution Service. One of his most effective reforms was to replace paper files with digital ones, an initiative that was never likely to generate publicity but, he points out, improved justice and people’s lives.

The manifesto pledge on repairing more potholes in roads is symbolic of how an incoming Labour government will seek to fix some things that really matter to people, rather than pretending it can fix everything all at once. A similar approach will be taken on relations with the EU. Instead of reopening the bitter rows over Brexit in which he once played such a prominent part, his early priority will be on piecemeal reforms, such as easing trade restrictions on food and drink and the introduction of a new veterinary agreement, which the Conservatives haven’t been able to secure because of their ideological approach to Europe.

Much of what people have predicted about prime minister Starmer will turn out to be wrong, not least because events in government will define him more than any speech made in opposition. It’s worth pointing out that neither Margaret Thatcher nor Tony Blair were properly defined until after winning a second term. Certainly, the first iteration of a Starmer government will not be the last. As Labour leader, he has often moved ruthlessly and silently towards his goal of victory.

Instead of proclaiming a single radical vision for changing his party he has just gone on and done it, bit by bit. His lack of political ideology or consistent attachment to a faction in Westminster has often allowed him to operate without the impediment of worrying too much about how much it hurts colleagues’ feelings. He will swiftly shuffle his team if he thinks they are underperforming.

In the build-up to the election, he started to have more meetings with backbenchers and shadow ministers, recognising it was necessary to build alliances, despite having little love for open-ended discussions that do not result in a decision. Even so, some of his colleagues still worry that he is not political enough. They suggest his “less-than-superlative communication skills” will leave voters underwhelmed when the scale of the challenges facing any new Labour government threaten to overwhelm.

When I once asked him if there is such a thing as “Starmerism,” his reply revealed his desire to stop talking about what he might or might not do. “I just want to get things done,” he said.

He knows difficult decisions lie ahead and has grown a thicker skin in the past four years. He often talks about how he’s got good “at blocking out the noise”. But ultimately, it will be his capacity to “get things done” that will determine how long he gets before there is another change in government.

Tom Baldwin’s book, Keir Starmer: The Biography, is published by HarperCollins