They may be tricky to pronounce, but isthmuses – those narrow strips of land that join larger territories together – have shaped the world we live in, says Stan Abbott.

Lacking the romantic allure of the island or the distinct cultural identity of the peninsula, the isthmus is a geographical feature that’s rarely celebrated, or even remarked upon.

As Philip Steinberg, professor of political geography at Durham University, puts it: “Part of the interest in islands comes from the whole thing of seeing islands as ‘laboratories’, supporting ideal societies or utopias… isthmuses don’t have that same level of idealistic discussion – they are, quite literally, just bridges to go somewhere else.”

But these unsung places have enjoyed immense strategic value throughout history – they can even change our climate. However slim they may be, they’ve helped shape civilisations the world over.

Nowadays, isthmuses are immensely useful: they avoid the need for ferries, bridges or tunnels when travelling overland. But in times when sea travel prevailed, the isthmus was an awkward obstacle.

Indeed, the very name isthmus is rooted in the first great European civilisation, derived as it is from the Greek, isthmos, meaning ‘neck’. The modern Greek town of Isthmia sits at the southern end of the the isthmus that separates the Gulf of Corinth and the Saronic Sea.

It carries fast connections by rail and motorway from Athens to modern Corinth and its Peloponnese hinterland. But students of Greek or Latin will know that ancient Corinth was an important city state, whose power and influence derived from its strategic trading and military location on the isthmus.

It was here, for about 800 years from 582 BC, that the Panhellenic Isthmian Games were staged annually in the years preceding and following the ancient Olympics. Today, the title of the Isthmian Football League, comprising teams in and around London, is a nod to the sporting spirit of those times.

Lord Byron, the unlikely hero of the struggle for Hellenic independence from Ottoman rule, successfully united the rival Greek factions to the east and west of the isthmus (under Prince Aléxandros Mavrokordátos, to the west, and Demetrios Ypsilantis, to the east) to pave the way for the first Hellenic Republic, whose capital was at nearby Nafplio, in 1827.

Byron recounted the gruesome Ottoman siege of Corinth’s acropolis in what must be the only tragic epic poem to include the word isthmus:

That sanguine Ocean would o’erflow

Her isthmus idly spread below:

Or could the bones of all the slain,

Who perished there, be piled again,

That rival pyramid would rise

More mountain-like, through those clear skies

Than yon tower-capp’d Acropolis,

Which seems the very clouds to kiss.

The Hellenic Republic was the precursor of the modern Greek state and hence Byron is celebrated as a Greek national hero each April and most Greek towns today boast a Byron Street in his honour.

Before the Byronic revolution, what we now call Greece was for three centuries part of the Ottoman Empire and, prior to that, of the Roman (and latterly the Byzantine) Empire, centred on Constantinople (modern Istanbul).

Ancient Greece, before the rise of Rome and after the fall of Mycenaean civilisation, was really just a patchwork of city states and wars between rivals at either end of the Isthmus of Corinth were both long and frequent.

The first Peloponnesian War saw Sparta, on the Peloponnese, and its ally, Thebes, at the northern end of the isthmus, battling it out with Athens for 15 years from 460 BC. Conflict was only ended by ratification of the so-called Thirty Years Peace – only for hostilities to begin again in 445 BC.

While Athens had the edge on the seas, Sparta took the battle to its rival, crossing the isthmus to occupy Athens in 404 BC. The conflicts were brutal and destructive, and Sparta’s reign was oppressive – Aristotle coined the term ‘oligarchy’ to denote rule by the rich, while Sparta itself gave us the enduring word, ‘spartan’, to signify the strict austerity that typified its rule.

But if Sparta found the isthmus a useful conduit for its armies, it was also a formidable barrier to the easy passage of goods and people by sea. For around 650 years, ships were hauled across the isthmus between the two gulfs, via the paved Diolkos portage route. This saved not just time, but also the stormy Mediterranean waters surrounding the Peloponnese. It has been calculated that it would have taken three hours and up to 180 men to drag a ship the four miles.

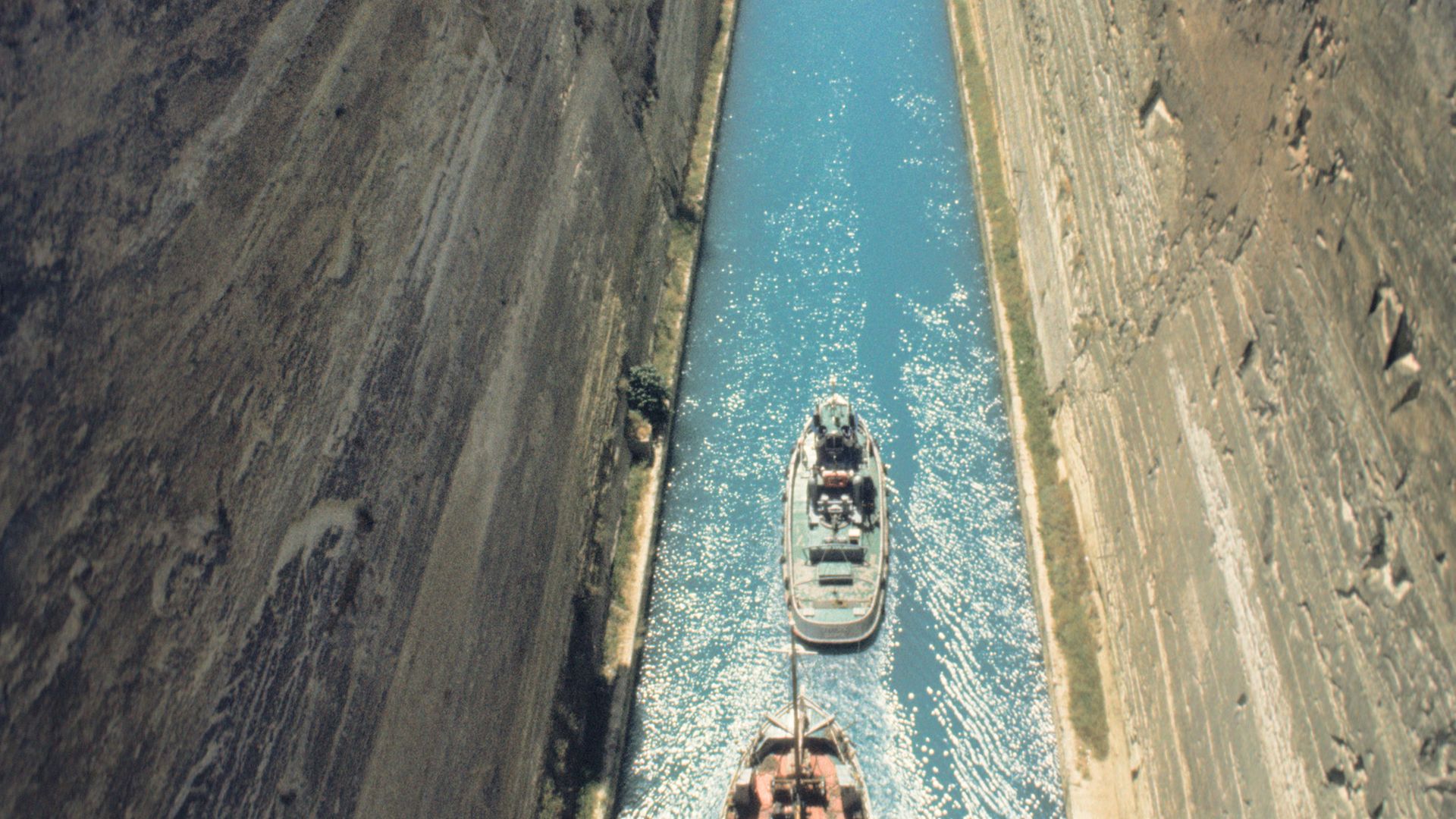

It was not until the end of the 19th century that the isthmus of Corinth was successfully canalised, even though the first efforts to excavate a channel occurred around the same time as the demise of the Diolkos. Perhaps it was the philosopher Apollonius of Tyana’s prophesy that anyone making such an attempt would fall ill that deterred such ventures.

Caligula was just one of three Roman emperors to die shortly after having expressed interest in a canal. Then again it may have been no more than Corinthian self-interest that kept the isthmus intact for so long, as a canal would have compromised its lucrative entrepôt trade.

The canal’s precipitous limestone walls today offer an imposing sight for tourists, but the canal failed ever to live up to its commercial ambitions, being too shallow and narrow for most ships, and prone to landslips, strong winds and tidal surges.

There is evidence of other diolkos in the time of ancient Greece, around the mouth of the Nile, and so it is perhaps appropriate that the world’s first great isthmus-breaching canal should have been not at Corinth, but connecting the Mediterranean and the Red Seas via a 120-mile canal across the Isthmus of Suez.

When the Anglo-French Suez Canal opened in 1869, it shaved a cool 5,500 miles off the shipping route around the Cape. During construction, much earlier canals across the isthmus were discovered, including an ancient Egyptian east-west channel connecting the Nile and the Red Sea and built around 1800 BC.

Suez’s game-changing brush with history came in 1956 when the UK and France, in collusion with Israel, flexed their post-colonial muscles, trying to retake the canal by force after president Nasser’s nationalisation of Egypt’s asset. When the USA, Soviet Union and United Nations forced an embarrassing climb-down, it was widely seen as marking the end of Britain’s days of empire.

The aftermath of this conflict led directly the Six-Day War of 1967, when Israel, faced with a blockade of its shipping in the Gulf of Aqaba, occupied the entire Sinai peninsula up to the banks of the canal – a situation that pertained until 1982.

Although the canal has seen major expansion of its depth and capacity since then, its closure for eight years following the Six-Day War provided a huge stimulus to the building of ever larger oil tankers, and latterly bulk carrier and container ships, with the aim of reducing costs when cargo was forced once more to go round the Cape.

The world’s other great inter-continental isthmus is Central America – all 1,140 miles of it. This winding strip of land includes as many as three strategic crossing points, of which the narrowest is Panama, at just 51 miles.

The economic benefits of connecting the Pacific Ocean with the Caribbean Sea via the Panama Canal (completed by the USA in 1914 after earlier French attempts foundered) are self-evident.

But, in geological terms, the isthmus itself is quite young and its impact on the whole world eclipses that of the building of the canal.

Although scientists continue to squabble over the precise timelines, prevailing opinion says the isthmus was completed less than three million years ago, creating a land bridge between the North and South American continents.

This concluded a process that began millions of years earlier with the collision of two oceanic tectonic plates, creating undersea volcanoes. These broke the water’s surface to create islands, the gaps between which were gradually filled in as the ocean floor rose and sediments collected.

Once the isthmus was complete, water could no longer flow between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, causing a major shift in ocean currents.

The Gulf Stream was redirected to the north, funnelling warm water all the way to Britain and Ireland and beyond, thus gifting the UK with a benign climate, which belies our latitude and stimulated our early agricultural prosperity.

On land, animals migrated in both directions along the isthmus, bringing armadillo and porcupine to North America, while the ancestors of bears, cats, dogs, horses, llamas, raccoons – and ultimately humans – headed south.

Like its Suez counterpart, the Panama Canal is also of immense strategic importance. So much so that the USA effectively created an extension of the American state to protect its interests.

The Canal Zone endured until president Carter returned the waterway to Panamanian sovereignty in 1977, only for George H W Bush to spark condemnation when he invaded Panama 12 years later to oust Panama’s de facto dictator, the former CIA asset, General Manuel Noriega.

Today, the Panama Canal has been enlarged to take more and larger vessels, but there remain projects to create a sea-level route, without locks, across the isthmus via Nicaragua, most recently backed by Chinese interests. And, further north, Mexico last year revived ambitions to link the Gulf of Tehuantepec by means of a new north-south railway to the Gulf of Mexico. However, the project faces significant opposition from indigenous communities in its path.

The Jutland peninsula cuts off insular Denmark, southern Sweden and the Baltic Sea from a more benign oceanic climate. The border on the isthmus connecting Jutland with Germany has shifted north and south at different times in history.

After Prussia conquered Schleswig-Holstein, the Kaiser created a new 61-mile canal to link the North Sea and the Baltic and facilitate the movement of both cargo and warships. It followed in part the course of an earlier Danish venture.

In 1920, the border slipped south again as Denmark was redrawn, but the Kiel Canal remains wholly in Germany. Its western end was the scene of the Battle of Jutland, the only major sea confrontation during the First World War.

The Crimean isthmus has seen its fair share of unrest, from the Crimean Wars to the recent conflict between Ukraine and Russia, which now occupies the Crimean peninsula illegally. The North Crimean canal does not cross the isthmus, but, rather, was built to convey fresh water supplies to Crimea. In a recent turn in the simmering stand-off between the states, Ukraine dammed the canal, creating an enduring fresh-water crisis for Russians in Crimea.

Great Britain (excluding its peripheral peninsulas) has no true ‘large scale’ isthmuses, but its two narrowest sea-to-sea points, from Solway to Tyne and Clyde to Forth, are both relatively narrow and were of strategic importance in Roman times. Hadrian chose to create a formal imperial frontier between Tyne and Solway; Antoninus had only brief success in redrawing the line 100 miles further north. The latter gap is crossed by the 35-mile Union Canal, built for seagoing vessels and opened in 1790.

In the true tradition of isthmuses the world over, the lands between Solway and Tyne have suffered more than their fair share of conflict. Successive wars between England and Scotland bequeathed a shifting border in which banditry ruled and gave rise to the enduring term of Border Reivers (or robbers), from which the English word bereaved is derived. Fanciful plans to link Tyne and Solway by canal have emerged from time to time.

Curiously, suggests Philip Steinberg, isthmuses did once enjoy a more powerful symbolic place in the world. Early cartographers demonstrated a strong association between insularity and sovereignty, he says, to the extent that they would depict countries as islands, even when this was not the case in reality. Early navigation tools, the so-called portolan charts, were a case in point, with some in the 16th century going so far as to depict Scotland as an island, separated from England by a narrow channel.

Some, says Steinberg, chose to hedge their bets, however. In a 2005 paper for the Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography, he writes: “A number of other maps from the era appear to be attempting to represent a middle ground between the two-island and one-island images of Britain.

“On these maps, a distinct channel is drawn between the two islands, but it fails to go all the way from one coast to the other, or, in other cases, there is a narrow isthmus that bisects the channel and joins the two would-be islands.”

The passage of five centuries now sees England and Scotland drifting towards increasing insularity once more: the metaphorical isthmus connecting the two nations appears increasingly slender, buffeted as it is by the turbulent waves of political difference and ill-thought Westminster commentary.