Oh I do like a Brexit by the seaside … Quintessentially British seaside town Skegness voted in droves to quit the EU. We went for a stroll along the pier and found ourself wondering whether the locals might be in for a shock

After spending most of the morning being battered by brutal North Sea winds, and failing to come across one single person – whether resident or day-tripper – who will admit to being a Remainer, I need a drink.

I have arranged to meet Phil Gaskell at the Seaview Pub on the front. A former Green councillor who defected to the Labour Party, Phil’s take on Brexit promises to be an antidote to the hogwash I have been subjected to for the past few hours. There are only so many ‘we’ve-got-our-country-backs’ and ‘immigrants-are-taking-our-jobs’ a poor, wind-lashed, metropolitan liberal can take.

Even the seagulls circling the Jolly Fisherman statue appeared to be squawking aggressively at me. Hopefully, like the bracing sea breezes Skegness is famous for, Phil will prove to be a breath of fresh air.

My mood, however, is hardly enhanced when he reveals that he, too, voted to leave the European Union (‘to get rid of Cameron’) and that we happen to be sitting in a UKIP pub. It is at this point that I notice all the black-and-white Winston Kime photographs decorating the walls. They are very poignant and appeal to a nostalgic view of 1950s Britain: the Good Old Days before the country went to hell in a handcart.

‘The Government will not listen,’ explains Robert Westhead, Phil’s mate. ‘People are fed up. But I wouldn’t like a real Hard Brexit. It is possible things could turn out well. You just don’t know. But I worry about trade. I wouldn’t like a bad deal, with everything going up and businesses going bust.’

As Phil explains why he, personally, doesn’t regret Brexit – in any way, shape or form – a voice at the bar pipes up: ‘You need to remember who pushed for it.’ The voice belongs to the pub landlord, Mark Dannatt, a member of the UKIP-run district council. Mark is referring, it turns out, to the patron saint of Brexitland. ‘Nigel Farage is the only one with any bollocks,’ he proffers. ‘Never heard of him,’ quips Phil.

Mark hands me a leaflet – ‘for your guidance’ – entitled ‘Believe in Britain’. I suddenly lose my thirst for alcohol – a bit too early in the day and all that – and order, instead, a cup of tea. Which, it is pointed out, like Skeggy itself – and the Butlin’s holiday camp just up the road – is a British institution.

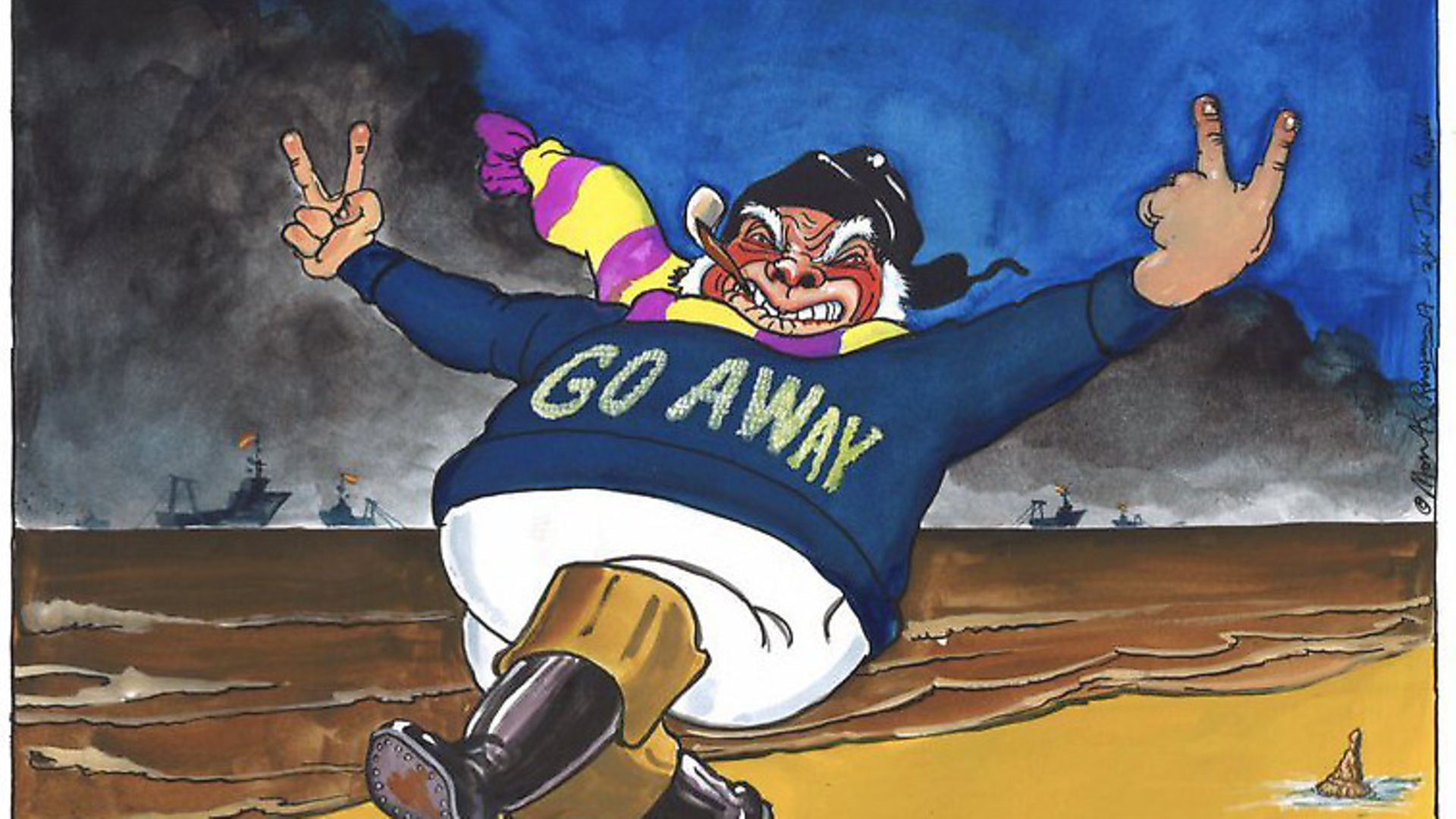

The small Lincolnshire town is, indeed, a quintessential English seaside resort. It inspired a famous and widely-recognised 1908 railway poster featuring the aforementioned fisherman merrily waving his arms underneath the caption ‘Skegness is SO bracing’. It boasts a population of almost 20,000 and myriad amusement arcades, funfairs, bingo halls and caravan sites.

Being just out of season, most of these are, at the moment, either closed or empty. But you can still enjoy the delights of fish and chips, sugary doughnuts and ice cream and, if you’re feeling particularly brave, hire a wobbly, red-and-white striped deckchair next to the pier on the sandy beach.

The great hope, in Brexitland-by-the-sea, is that quitting the EU will trigger a resurgence in domestic tourism, but as I left the pub and made my way along the near-deserted North Parade I couldn’t help wondering whether this eerie scene of abandonment was a portent of the calamitous future ahead. One sign I passed seemed to sum everything up: ‘No jumping off the pier.’

This is surely what the resort, and indeed the whole country, is in the process of doing. After triggering Article 50, it should take two to three years to complete our divorce from Brussels – although some Skegnessians have already jumped the gun and taken back control of their own borders.

One 22-year-old chap, Mathew Lewis, made the local news when he erected a barrier, constructed of wheelie bins, a push chair and children’s toys, across Sea View Road, declaring it to be an ‘EU border crossing’. He then demanded motorists show him their British passports. When one driver failed to produce the required document and impertinently attempted to clear a path,he was assaulted.

At least Lewis didn’t make him pay for the barrier.

So, is this the shape of things to come? By 2020, will we all be bracing ourselves for much more frightening Little Englander variations on this Trumpite theme? Will deprived seaside resorts like Skegness – in an Office for National Statistics report, it topped a list of the nation’s most impoverished coastal towns – be prone to social unrest? It is not exactly, unlike nearby Boston, a byword for Eastern European migration, but anti-immigrant feeling – if my miserable morning is anything to go by – clearly runs high.

During last year’s referendum campaign, Polish Educational Association chairman Wojciech Pisarski went to a radio debate and was shocked by what he heard. ‘A farmer from south Lincolnshire who employs dozens of migrants said he’d been to Holland,’ he tells me, when I at last make contact with, it seems, the only Remainer in the village. ‘The farmer said the migrants were described over there as dirty and carriers of disease. The whole hall erupted into applause. Appalling things are being said, being given public approval. Strong xenophobia was whipped up by the Leave campaign, UKIP and the right-wing media.

‘There’s a fair bit of bigotry. When the referendum took place, the road coming into Skegness was plastered with Vote Leave posters, I Want My Country Back ones and so on. I saw the people putting those posters up. I’ve heard they were involved with the far right. People like Britain First, the EDL and the National Front.

‘My wife has an elderly aunt living outside Skegness in a village. She reads the Daily Mail and laps it all up. I asked her why she voted leave. ‘To get rid of all these Poles’. I asked her how many Poles has she met? ‘None’. When I grew up in the 1950s and 60s, ‘foreigner’ was a common insult. Things changed for the better – but now we are back to what it used to be. Racism, xenophobia are the accepted norms. It’s swung back again. I fear that we’re going to replay the 30s. There are elements of what happened in Germany. How far are we from allowing migrants and refugees to become the equivalent of the Jews in 30s? You don’t need to wear a fascist uniform to be fascist.’

Last year, the local Butlin’s became embroiled in a racism row after a wrestling show, aimed at children, featured a villain bearing a ‘Muslim flag’. The audience were encouraged to boo and hiss when he appeared on the stage and one dad tweeted: ‘I felt I was dropped into the middle of a Britain First rally. Out came ‘Hakim’. The Islamic flag waving baddie. ‘BOOOOO’, we were told. Then came Union flag trunk wearing ‘Tony Spitfire.’ Yes Tony Spitfire, ladies and gents. ‘En-Ger-land!’ he thumped over and over.’

A few months later, during a day out in Skeg, a Muslim family claimed they were stared at and treated like aliens. The Skegness Standard quoted a hijab-wearing member of their family as saying: ‘It didn’t really bother us until we walked past the pub and a man shouted ‘terrorists’.’

I discovered Wojciech, who was born in Britain to Polish parents a few years after the war, when I picked up a copy of the Standard in the newsagents next to the Ex-Servicemen’s Club, which is raised on a platform above the seafront. He set up a Saturday school to help Eastern Europeans in the area improve their language skills.

‘Skegness is now home to many migrants from Commonwealth countries and from the Eastern European countries that joined the European Union in 2004,’ he told the paper. ‘They find it difficult to make friends in the wider community due to their poor grasp of English and working alongside other Eastern Europeans in fields, factories and local businesses.

‘The future for them is uncertain with Brexit – farmers are already saying there is shortage of workers. But many want to stay and become more integrated in the community.’

Interestingly, when we met at the bed and breakfast hotel I was staying at, Wojciech preferred to emphasise the classes which are teaching second-generation Poles their parents’ native language. ‘Kids go to Saturday school for three hours a day,’ he explained. ‘They can speak Polish but they need to learn to read and write it. Their parents might decide to go back to Poland. With Theresa May not guaranteeing their status, it is possible they will decide to go back. If they do, they need to have the basics of the Polish language.’

This might be music to the ears of all barrier-building, turn-the-clock-back Faragists but, as Wojciech points out, by 2020 a reduced migrant workforce could have a devastating effect on the local economy. ‘Britain now has an economy addicted to migrant labour,’ he said. ‘We needs migrants for the NHS of course. But the hospitality industry is addicted to migrant labour. Lots of enterprises have sprung up as a result of people who work hard and for long hours. You get people who work in cafes and restaurants, in the kitchens and so on – and Butlin’s has a fair number.’

But with a post-Brexit devalued pound, won’t British holidaymakers swap the Sunny Med for Costa del Skeggy? Isn’t the one positive side-effect of all this madness an increase in staycationing?

‘Brexit will lead to an almighty recession,’ he said. ‘People will have less money in their pockets to be spending on their days out. It’s a very brittle economy locally. It’s seen as a cheap holiday for less well-off people. But if people don’t have money in their pockets, they won’t be able to afford a cheap holiday.’

A Hard Brexit will leave vulnerable places like Skegness susceptible to crisis. The town is part of the East Lindsey district where 70% voted to leave – in Boston it was 5% higher – and the majority of residents are currently feeling empowered. But in three years time, after we’ve left the single market and fallen back on World Trade Organisation rules to manage our international trade, the agricultural industry could be facing tariffs on 90% of its EU exports by value and a raft of new regulatory hurdles. ‘Agriculture will be affected by the lack of access to the single market,’ said Ian Dunt, author of Brexit: What The Hell Happens Now?

‘If [International Trade Secretary] Liam Cox cocks it up, and we don’t get a deal – which is very possible – agriculture is finished in the long term. In three years time, it could be dying on its feet.’

In 2020 Britain, completely cut off from Brussels and the free movement of labour, it will be hard for local farmers to find the workers to harvest their crops. Caravans housing low-paid Eastern European migrants could be seen on my train journey between Boston and Skegness.

Staples Vegetables, a 10,000-acre farm and packing site located between the two towns, is one of the biggest employers of immigrant workers in the area. It has had to recruit directly from Romanian and Bulgarian colleges because, according to a spokesman, ‘without them we wouldn’t be able to grow our crops in the UK … we have a lot of problems with local people who can receive benefits. We have people who ring up and say ‘I’m ringing up because I’ve got to’ and you get the impression they’re at the job centre and they’ll tell you when they’re applying that they’re only doing it because they have to.’

Wojciech’s passing reference to Butlin’s intrigued me. Could it be that the epitome of a sepia-tinted, Hi-de-Hi version of 1950s’ Britishness – all knobbly knees competitions, cold fried eggs and mother-in-law gags – is also dependent on migrant labour?

Designed in 1936 by Billy Butlin on the back of a cigarette packet, and built on a muddy field, the Skeggy resort is the birthplace of the globally-renowned chain. After pioneering the Great British holiday camp vacation, it went into decline in the 1980s – some of its clientele switching to cheap foreign package holidays – but for the last decade it has been booming. It now attracts more than four million visitors each year, generating £480m for the local economy.

I jump on one of the many buses headed for the ‘resort’ (not, as I am to learn, ‘camp’) and, as I am being given a whirlwind tour of this ’21st century take on the traditional chalet self-catering holiday’, I begin to shed all my preconceptions about the place. There are still, thank God, loads of fun-organising redcoats milling around – unlike Skeg itself, it now operates off-season – but it has clearly reinvented itself for a more politically correct, chillaxing age. Mother-in-law jokes have been banned, loudspeakers no longer blare out ‘wakey wakey campers’ alarms first thing in the morning and they’ve even jettisoned the apostrophe – Butlins as opposed to Butlin’s – sticking two fingers up to the grammar Nazis.

‘It’s pretty much the old traditional holiday but revamped for the 21st Century,’ explains my tour guide Diane Kay, PA to resort director Chris Baron. As we take a look inside an ‘apartment’ (not a ‘chalet’ any more) we pass two Hungarian members of staff, both in their mid-20s, who have been here for two years. ‘It’s given us a great experience,’ Henrik said. ‘I mostly clean. I finished my degree and went to a business school in Budapest. My career ended because my was mother sick and I take care of her. I make some money and go back when I have a chance to.’ His friend, Robert, added: ‘It’s great we can work anywhere. There are English here, and Hungarians and Polish. I hope, eventually, to have a chance to have a career in marketing.’

The Islamic flag-waving incident was, it appears, a one-off occurrence. ‘Times have changed,’ says Diane. ‘We use a lot of people from abroad. Maybe about 30% who work here are Eastern Europeans. We’ve got an assortment – Hungarians, Polish, all sorts. I don’t mind people coming and working in this country. If my children wanted to go and work abroad, well it’s the same thing. Sometimes we can be a bit selfish, saying why are these people here and what are they doing?’

A report in the Sunday Mirror a few years ago revealed that Butlin’s often sent recruiters to Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia because many unemployed locals were not up to scratch. This upset the Skegness UKIP branch. ‘The Europeans are very well educated people,’ Diane said. ‘Some of them who have been here a few years now are in quite good jobs – like team leaders. Everybody is entitled to the same rights. They like us – and it’s a shame that some British people don’t like them. Everyone has an opportunity here, the English and the Eastern Europeans. We’re all in this together.’

Butlin’s, like the NHS, is a national treasure. And, like the health service, its workforce – and the Lincolnshire economy – will take a big hit if, by 2020, Britain has left the EU without a deal. Diane worries that a third of the resort’s employees might be gone by then. ‘For about seven years we’ve had the Eastern Europeans coming here,’ she pointed out. ‘I think it is one of the things that has contributed to turning things around here – because they’re prepared to do the work that some of the British aren’t. Although they are well educated they don’t care (about getting their hands dirty). They just get on with the job. We try and recruit locally but who’s prepared to do it?’

This point is reinforced by the last Skegnessian I talk to before boarding the train out of Brexitland-by-the-sea. Ben (who doesn’t want to give his surname or reveal his job) was born and brought up here and has now returned after ten years in London. ‘A lot of immigrants are already leaving,’ he said. ‘If they refuse to recognise their right to be here, more will consider their positions and there will be knock-on effects on the NHS, on Butlin’s and on the land. A lot of the farmers will be unhappy losing a bit of their workforce.

‘When I came back after being away I was shocked by attitudes to minorities. There’s quite a lot of prejudice in areas like this. It’s a very strong UKIP area. This area needs immigrants, as the country does. I’m all for the freedom of movement of people. I dread to think what will happen in three years time. The whole country could be broken up – Scotland, maybe Ireland – and there could be more discrimination and prejudice against immigrants with a rise in populist nationalism. It will give groups like UKIP and the far right succour if we go down the hard road to Brexit.’

At the railway station I read in the local paper that Fantasy Island is back in business. This is not a satirical reference to a Nige-worshipping, immigrant-free zone ruled over by Nobel Peace Prize winner Paul Nuttall. It is a report about the unveiling of a £3m investment at the Ingoldmells theme park next to Butlin’s. Earlier in the day, after missing my stop and getting off at the family amusement site, I had a quick peek at the dodgems, big wheel, ghost train and waltzer. Most impressive of all was the Millennium Rollercoaster. The last time I had been on one of these turbulent, scary, high speed rides was at Alton Towers. It was called, appropriately enough, Oblivion.

Anthony Clavane is an author and commentator. His latest book, A Yorkshire Tragedy, is published by Quercus