A new exhibition focusing on Pompeii’s eating and drinking habits provides a powerful, often poignant, portrait of a dynamic city frozen in time. Richard Holledge reports.

Cheers. Or salus as the drinkers in the taverna would have said as they quaffed another mug of wine or two. Why not? An autumn evening, the day’s work done, what better than to gather in one of the many bars that lined Pompeii’s Via dell’Abbondanza to gossip and drink.

How can they know that this would be their last evening alive? They had shrugged off the small tremors that had shaken the region for four days and, anyway, the sign outside the pub owned by one Euxinus sported a golden phoenix, the mythological bird that symbolised hope and renewal, and the cheery message: ‘Phoenix felix et tu’ (‘The phoenix is lucky, may you be too’).

Nothing warned them that on October 24, AD 79, Vesuvius, the volcano that towered over their city, would erupt with such ferocity that it would throw a cloud into the air which reached as high as 40,000 feet – higher than most jets fly today.

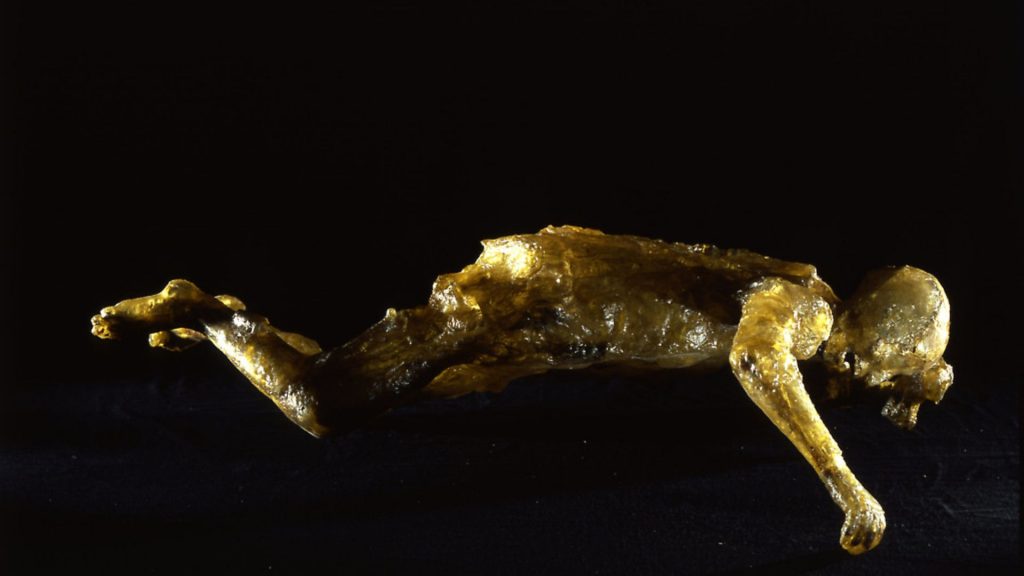

The rain of stone and the avalanche of ash and rock smothered first Herculaneum then Pompeii, killing as many as 16,000 people. They were buried alive. In effect, cooked to death by the ash which reached temperatures of 400 degrees centigrade.

Last Supper in Pompeii at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, demonstrates with great detail and an engaging sense of humanity that while the volcano took all and everyone before it, counter-intuitively, the very heat of the immolation and the depth of the ash preserved many of the buildings and the frescos.

Astonishingly too, so much evidence of the people’s food and eating habits survive that we know almost as much about the intricacies of their lives, their intimacies and, indeed, vanities as we might have done 2,000 years ago.

But back to our lads in the bar. Thanks to a collaboration with the Parco Archeologico di Pompeii, curator Paul Roberts has assembled 300 objects and deployed new evidence and existing testimony to interpret the frescos, inscriptions, pots and pans, to glean a great deal about their behaviour – not much different from today, in fact, though these pub-goers may be more likely to be regulars at Wetherspoons in Hammersmith than a gastro-pub in Chelsea.

At the time of the eruption there were 600 taverna in Pompeii, about 160 equipped for food and drink. Bars known as popina were simple, one-stop joints opening on to the street which inevitably perhaps had a reputation for bad behaviour from both customers and staff.

“I screwed the barmaid,” reads one boastful graffito. Another customer complains: “Damn you landlord, you sell us water and you drink the wine.”

The poet Horace condemned popina as greasy and filthy and Juvenal accused them of being frequented by coffin makers and runaway slaves. Oddly, so paranoid were some of the Roman emperors that these tavernas were sources of unrest where malcontents gathered to drink and turn to violence that they tried to ban the sale of… food.

Poor fare it was too; sausage, ham or a bowl of tripe with dried beans, boiled lentils and millet with bread, figs and pastries. All washed down with watered wine.

Other bars, known as caupona were a tad more sophisticated with a large room for eating and drinking at tables. Some had gardens, small vineyards and even gazebos to sit in the shade.

There was clearly money to be made; in one caupona 1,600 bronze coins were discovered, which would have been enough to buy a mule and still get some change.

The drink of choice was wine served from large jars – or dolia – sunk into the stone counter of the bar itself. The slopes of Vesuvius, then as now, were good for growing vines and there were 40 local farms and estates with vineyards, but the finest vintage was Falernina from Campania, north of Pompeii. One landlady by the name of Hedone told her customers: “You can drink wine for an as (a Roman coin of little value) better for two asses and Falernina for four.”

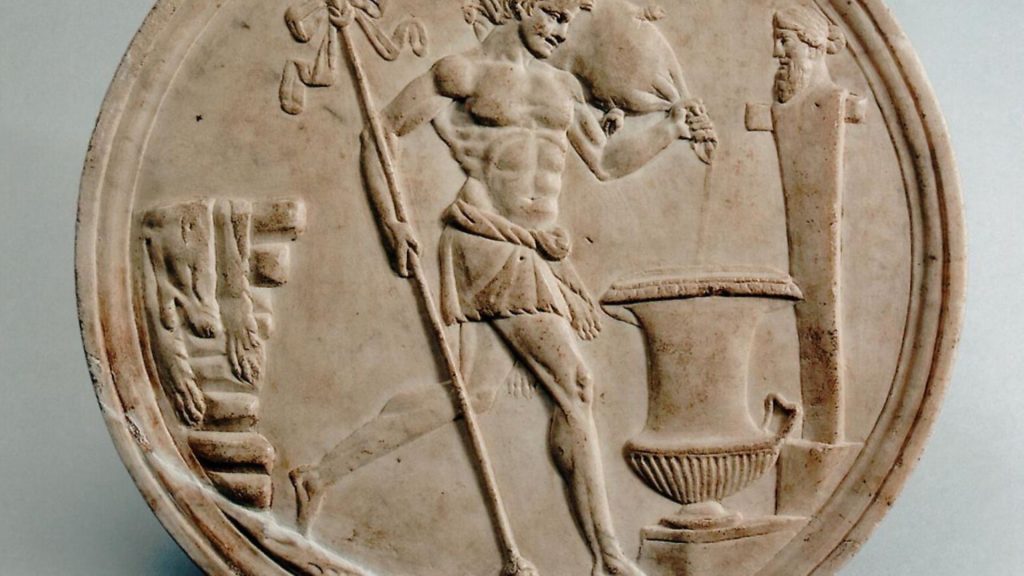

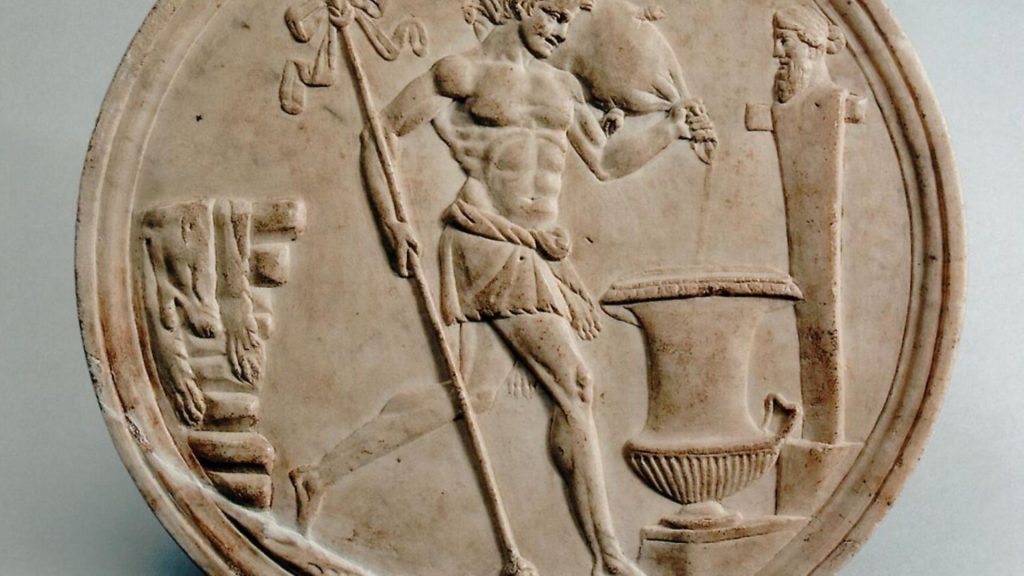

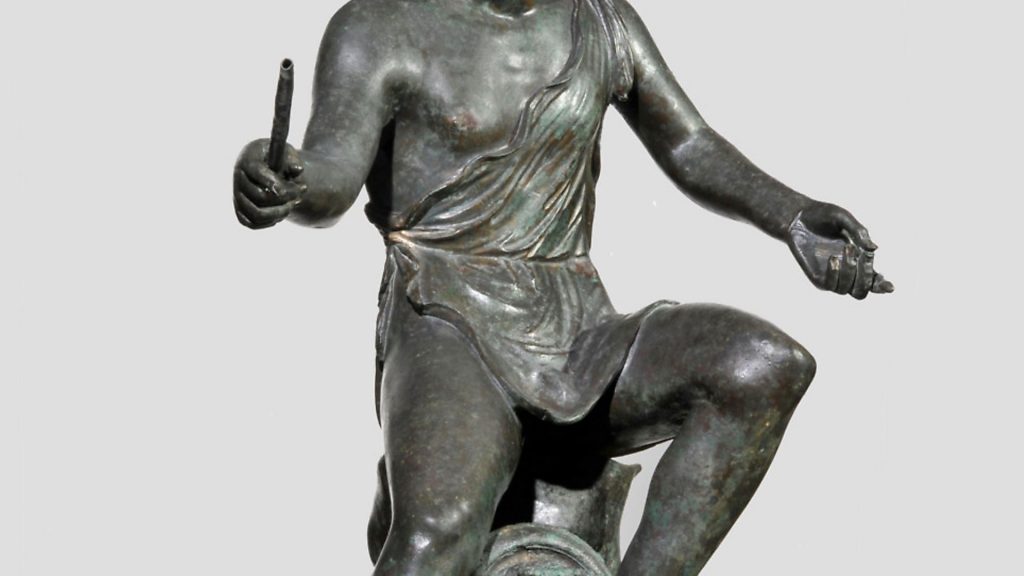

Records uncovered from the ashes suggest that 100 million litres of wine were produced in the year before the volcano struck. No wonder images and sculptures of Bacchus abound, none more strangely exotic than a fresco which decorated the home of a wealthy Pompeiian of the god draped in grapes and standing in the lee of Vesuvius with snakes and birds circling.

For the rich, eating and drinking at home was an altogether more sophisticated affair than the pub grub enjoyed by the hoi polloi. Guests made their way through the house’s hallway, or atrium, to the triclinium, the meeting place, where three couches were set in a U-shape, invariably beautifully decorated and overlooking gardens and shady courtyards where grapes, figs, fruit and olives grew. Some plants such as myrtle, oleander and daphne were imported from the Roman regions of the east and delivered in pots, rather like buying plants in garden centres today.

In the House of the Golden Bracelet, which derives its name from the discovery of the remains of a woman wearing a thick gold bracelet, a fresco of a garden has golden orioles, thrushes and black birds flitting through the undergrowth.

This is one of the high points of the exhibition; the fresco was transported from Italy in crates and now fills one wall of the gallery. Fabulous.

Many homeowners commissioned frescos to pique their senses as they ate. In The House of Ephebe, there is an Egyptian-inspired depiction of pygmies eating while others are having vigorous sex, oblivious to the diners – and to a waiting crocodile in the water below – while in The House of Venus, appropriately, the goddess Venus reclines in languorous nudity on a shell.

Banquets were held in the convivium, which gave us the word convivial. Men and women mixed together on couches and would eat reclining, always leaning on their left because the stomach extends more easily on that side, leaving more room for more food and drink. No wonder they needed a sick bowl and a portable urinal.

While they lounged about dipping pieces of food into sauces, slaves would circulate topping up their wine with a jug of warm water, honey and spices,

Unsurprisingly the slaves did all the work. They shopped for the food, they cooked it and they served it. All the cooking took place on a flat platform with burning charcoal or wood and richer houses even had an oven, which might explain why the area is renowned for its pizzas even today. Cooks used bronze colanders, pans with long handles, steam cookers and strainers. There is even a mould in the shape of a chicken which would have sat nicely in the middle of a wealthy man’s table.

We can get further insight into the food from lists scratched on to the wall of an atrium which included bread, oil, leeks, onions and cheese, as well as dates and incense. A mosaic of tiny cubes graced the floor of an unknown, but obviously well-off, householder with depictions of sea life – octopus, rays, cuttlefish, eels and a choice selection of fish.

In the House of Aulus Scaurus, a businessman who made his fortune from garum, a fermented fish sauce which Pliny the Elder described as “exquisite liquor”, mosaics of his bottles were laid into the floor of his house with the inscription: “The flower of Scaurus’s mackerel garum from the factory of Scaurus.”

The rich dined off much the same food as their poorer countrymen but they enjoyed better cuts of meat, often roasted, fried fish, mutton instead of pork and expensive fruits such as dates and mulberries.

Treats included dormice stuffed with pork mince and songbirds in a sauce of black pepper and ginger. From the fresco in the House of the Greek Epigrams we can see they tried cock’s head and feet and we know they feasted on peacocks and flamingos and delicious peaches newly arrived from the east.

The day began with a breakfast, lentaculum, of olives, bread and cheese followed after midday by prandium, a lunch of meat, bread and vegetables and later cena, the main meal which might include appetisers such as eggs, seafood or snails, maybe sea urchins baked with bay leaves, before a main course of goat, poultry or rabbit rissoles. One speciality was to take the womb of a sterile sow, stuff it with a medley of pepper, cumin, leeks, rue and garum, add minced meat and pine kernels and “press into a well-washed womb”. Sounds gruesome – but not unlike haggis.

A sauce for conger eel was a favourite, using a fusion of flavours such as pepper, lovage, cumin and oregano. Onion, egg yolks, wine vinegar and garum gave it the final touch. Anyone for boar stuffed with live thrushes?

As the name suggests, the convivium was the place for parties. One fresco shows a woman and her companions, gathered around a table laden with drinking vessels. In a speech bubble above head she declares: “FACITUS VOBIS SUAVITER EGO CANTO” (“Get yourself comfortable I am going to sing”).

In response a man urges her on: “ES ITA VALEAS” (“Yes that’s it, you go for it”).

In a women-only bash they let rip in what could be a first century hen party, playing music and, judging by the pile of bottles, drinking more than is good for them.

And all the time the wealthy home-owner had to prove his status with expensive silverware which were displayed on the dining table – cups, jugs, drinking horns and bowls for hand washing.

Behind the scenes, however, a different story. The kitchen formed the grubby engine of the house. “Not the room that sold the house,” jokes Roberts. They were small, poky, airless, dark and very hot and they invariably shared space with the toilets. What a source of information they have proved to be for posterity, something the crouching figure on the toilet protected by the goddess Isis Fortuna could not have realised.

Above his head is inscribed: “CACATOR CAVE”, which rather crudely translates as ‘crapper beware’. From those ancient latrines have been culled traces of fruit, figs, onions and cabbage, as well as peas, chick peas and olives.

The staple for both rich and poor was bread, though the wealthy preferred white bread to the grittier flour which ruined the eater’s teeth. There were 30 bakeries plying their trade when the volcano erupted, and one fresco depicts bread being handed out to the hungry poor – possibly an act of charity, more likely a bribe to ensure a vote in an election.

Eighty loaves were unearthed from the bakery of one Modestus in 1862 and loaves of bread were preserved by the carbon of the volcano. It is poignant to imagine a baker putting his bread in the oven then leeing as the ash poured down, only for his loaves to survive for 2,000 years.

For an exhibition about death and destruction it is nonetheless vibrant with the minutiae of everyday life.

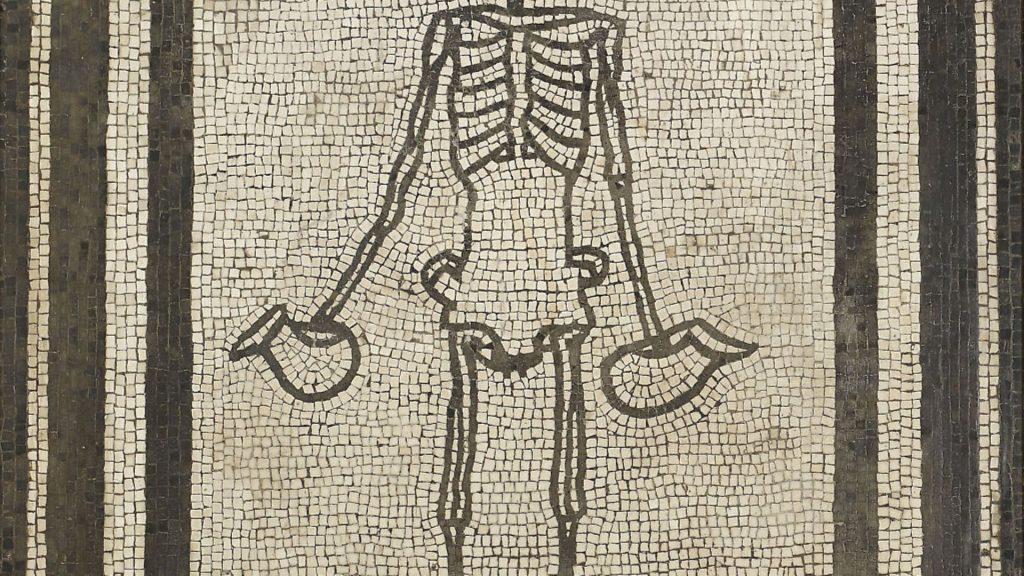

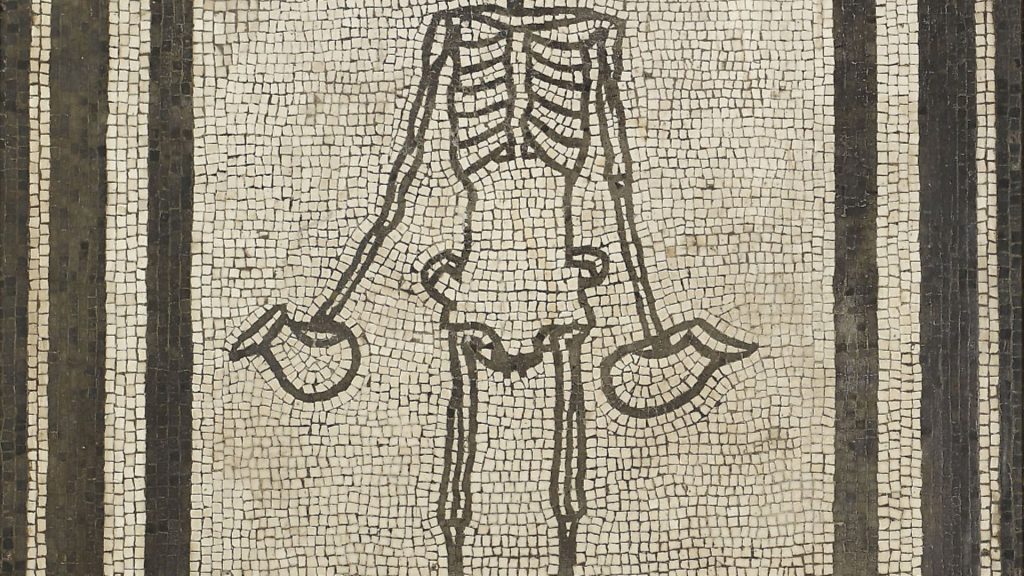

The reality of death is evident but the sense of hope – or maybe the mockery of death – takes the form of a skeleton which was found on the floor of a triclinium.

He seems to be walking towards us, he is grinning and he holds two wine jugs. Death has no fears for him and maybe not for us.

The poet Horace, who died 50 years before the cataclysm, would have understood. So too would any one of our drinkers in the Golden Phoenix had they survived Vesuvius.

“Carpe diem, quam minimum credula postero,” he wrote. “Seize the day, put very little trust in tomorrow.”

Last Supper in Pompeii runs until January 19, 2020, at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford