Famed for his depictions of four-legged creatures, the painter went to extraordinary, grisly lengths to understand the animals. RICHARD HOLLEDGE explains.

Curious cove, George Stubbs. The high society painter of splendid, high-stepping horses was also a figure of “vile renown” who, in his striving to perfect his art, dissected human bodies and later, driven by his passion to understand the anatomy of horses, spent 18 months in a rented barn in remote Lincolnshire dismembering their carcasses.

This obsession to understand how humans and animals worked is investigated in George Stubbs: ‘all done from Nature’ at the MK Gallery in Milton Keynes, which has gathered together more than 40 paintings and 40 prints and drawings in what is the most extensive exhibition of his work for more than 30 years.

Stubbs (1724-1806) set out to be a portrait painter in an era of great portraitists such as Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough and Thomas Lawrence and judging by his depiction of his early patrons Sir Henry Nelthorpe and his second wife Elizabeth in 1746 he would have made a steady living, though without matching the virtuosity of those masters.

But Stubbs was, no doubt, influenced by the intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of radical politics, philosophy and sciences in Europe during the Enlightenment. He was driven by his thirst for scientific knowledge and, when it came to his art, he wanted to understand what lay underneath.

The son of a leather worker in Liverpool, he must have been used to animals being stripped of their skin and become inured to the sight of the blood, the bones and the muscles.

In about 1745 he moved to York and got to know a surgeon who encouraged his fascination for anatomy. He was commissioned to illustrate a book by male midwife Dr John Burton entitled An Essay Towards a Complete New System of Midwifery, Theoretical and Practical.

His illustrations of the foetus are nothing if not graphic, especially with the drawings of crude instruments of childbirth alongside, but what adds to the sense of queasy unease is the strong possibility that the bodies used for his research were women supplied by grave robbers. Hence his “vile renown”.

The quest to discover how bodies worked became obsessive. Sponsored by Sir Henry Nelthorpe, he moved to the Lincolnshire village of Horkstow in 1756 where, helped by his longtime companion Mary Spencer, he spent 18 months dismembering as many as a dozen horses.

A friend, one Ozias Humphry, described the work in unflinching detail – flaying the skin to expose the carcass, cutting through the muscles until he reached the lungs and intestines, throwing away the bowels, and dissecting the head: “After having cleaned and prepared the Muscles &c. for the drawing, he made careful designs of them, & wrote the explanations which usually employed him a whole day…

“And so he proceeded until he came to the skeleton – It must be noted that by means of the Injection [of wax or tallow] the Muscles, the Blood vessels and the nerves, retained their form to the last without undergoing any change.”

What Ozias does not dwell on is the drawing of the blood from the jugular vein or the way the bodies were hung on hooks from the ceiling, and he leaves it to us to imagine how the couple dragged the heavy corpses around, no doubt spattered with blood, the stench in the heat of summer, the difficulty of dissecting a frozen corpse in winter.

His grisly research completed, Stubbs journeyed to London in 1759 with his pencil and chalk drawings and his treatise, The Anatomy of a Horse.

He taught himself to etch the plates himself and after six or seven years he produced 18 plates and 50,000 words of explanation. On the title page he wrote “All done from Nature” and hoped his findings “might prove particularly useful to those of my own profession”.

The result is both spectral and scientific; ghostly cadavers trot towards you from an equine graveyard accompanied by detailed explanations such as, “Finished study for the First Anatomical Tale of the Muscles of the Horse; lateral view with the skin and subcutaneous fat removed and some of the upper blood vessels exposed”.

As the contemporary poet Roger Robinson wrote in a piece specially commissioned for the exhibition catalogue:

Convinced that the body was host

To the horse’s spirit he began making martyrs

Of horses, subjecting them to jugular death.

As an eerie complement, the exhibition also features the skeleton of Eclipse, the most famous racehorse of the 18th century. When the beast died in 1789 he was dissected (not by Stubbs) and found to have a big heart and nimble frame, ideal for a racer, and resurrected as a skeleton with only the hooves missing. They were, apparently, made into inkstands.

Stubbs painted him three times, though considering Eclipse never lost a race his portrayal is distinctly static, there is nothing of the drama of the gallop here, perhaps because Stubbs had no interest in the chase. Eclipse went on to sire 300 winners and an astonishing 95% of all thoroughbreds alive today are directly descended from the stallion.

By the 1760s Stubbs had met the leading portraitist of the day, Joshua Reynolds, who was impressed by the treatise and introduced him to his circle, many of whom were wealthy aristocrats whose great passion was horse racing. As one wag remarked, they would rather own a picture of their steed than their wife, and Stubbs, obsessed as he was with the inner workings of his subjects, was also quick to see that there was money to be made from the commissions of the rich and famous.

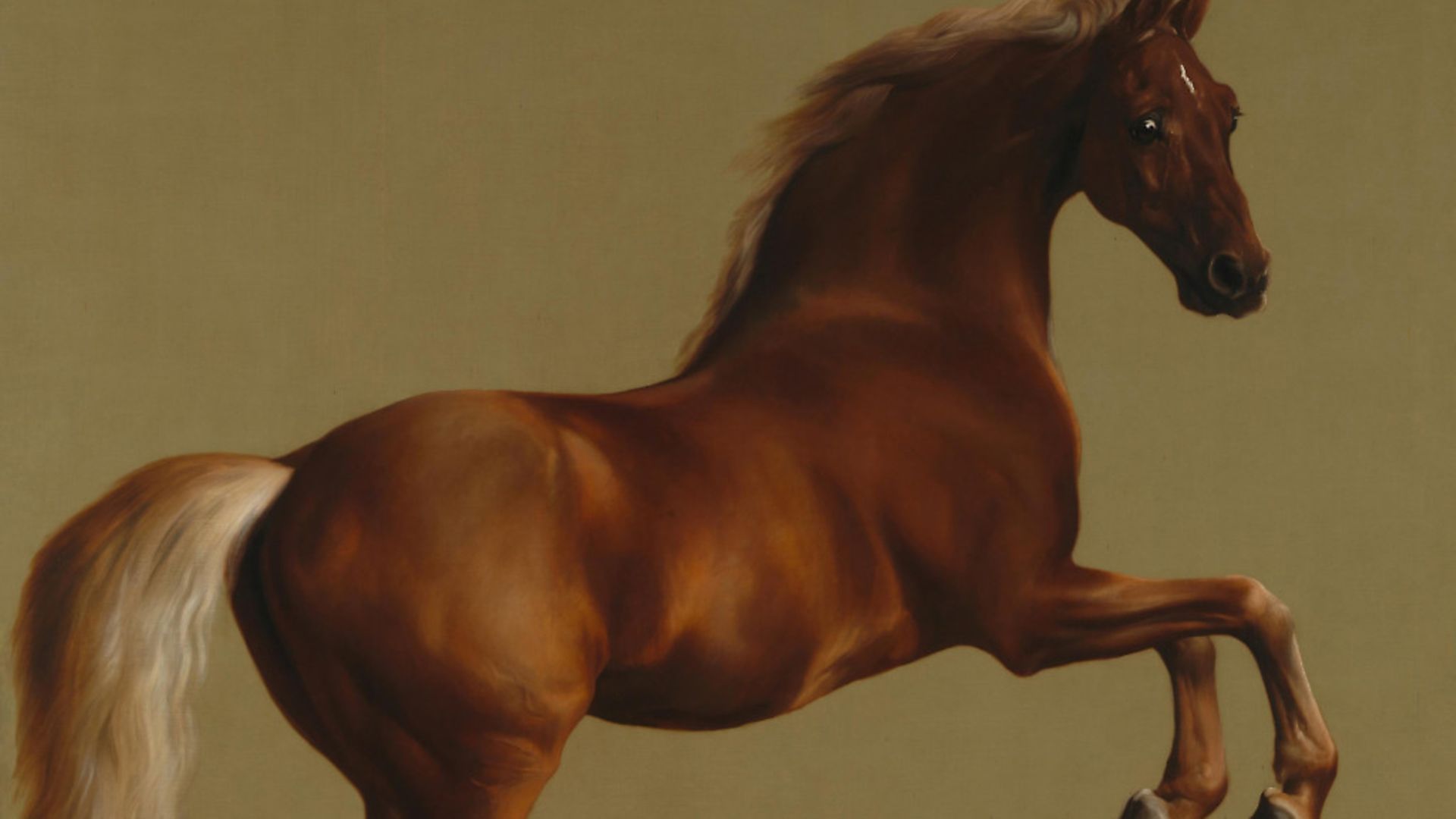

When he was Prince Regent, George IV commissioned 14 works by Stubbs and it was the Earl of Rockingham who commissioned his best known painting, the stupendous, prancing stallion, Whistlejacket.

Originally the Arabian horse – named after a contemporary cold remedy containing gin and treacle – was to have had a rider, King George III, no less, who would have been outlined against one of Stubbs’s typical landscapes of trees, distant horizons and big pink-hued skies, but Rockingham ruled that the animal should stand alone in all his chestnut magnificence, arched neck and broad chest and muscular legs. Everything about him redolent of power and speed.

Rockingham suggested that Stubbs should paint the horse, the best landscape artist should paint the scenery and a leading portraitist the King.

A hint of how that might have been made to work is illustrated by a rare example of Stubbs’ working methods, which shows a completed horse with a saddle-shaped space left blank and an empty background presumably waiting for its rider to be added.

Many of the portraits are so posed, presumably to please the subject of the work, that they have a statuesque quality. One might expect some vigour in The Marquess of Rockingham’s ‘Scrub’, with John Singleton up (1762), considering Singleton was a top jockey of the day but not so, just the same formality that is bestowed on the keeper of royal forests in Joseph Smyth Esq, Lieutenant of Whittlebury Forest, Northamptonshire on a dapple grey horse (1762-64). The men strike stolid figures while the horses, particularly Smyth’s magnificent silver and grey stallion, radiate such contained energy it seems they could gallop off into the landscape.

Some works are reflective such as Mares and Foals in an Unfigured Background (1762), which is like an equine frieze with its flowing lines. Interesting to note that three of the horses are reproduced almost exactly in Mares and Foals in a River Landscape (1763-68) with only just a change of colour for one of the animals. Cut and paste, 18th century style.

The insight Stubbs’ had acquired from his dissections is evident in Lord Pigot of Patshull Riding a Spanish Charger (1765-68) which depicts this former Governor of Madras struggling to control his spirited steed which is high-stepping, muscles flexed, neck arched.

The Duke of Ancaster’s Bay Stallion ‘Blank’ Held by Old Parnam his Groom (1761) has the horse, which was given such an insultingly anonymous name because he was deemed not good enough for its owners, eager to escape the groom’s tight rein pulling back, its sinews straining.

It is tempting to anthropomorphise the feelings the animals might have had for each other or indeed their human owners. Stubbs himself did attribute emotions to them and he felt a kind of empathy for his subjects.

One can easily imagine some kind of ‘human’ exchange in Two Horses Communing (1777) and surely there is some sort of understanding between dog, horse and human in the Equestrian Portrait of John Muster on his Favourite Hunter Pilgrim in the Park at Colwick (1777-78), an endearing scene with a dog gazing up at horse and master.

There can be no doubt as to the terror and fury unleashed in Horse Devoured by a Lion (1763). Inspired by antique statues seen in Italy when making the Grand Tour, contemporary audiences thrilled to the naked power of the lion, jaws clenched, eyes ablaze as it sank its teeth in the body of its victim. The horse, eyes gleaming and teeth bared in terror, every muscle in its body straining. This is a complete contrast to his society images of gentlemen gently ensconced on horseback. This is nature, vicious, raw and unrelenting.

Stubbs did not restrict himself to horses. He painted just as many dogs and was happy to meet the demands of buyers eager for the exotic with such as Tygers at Play (1776), a Hump-backed Moose (1770), and Recumbent Panther (1778).

Best known, perhaps, A Cheetah and a Stag with Two Indian Attendants commissioned by Pigot in 1765 shows how Indians hunted with cheetahs by restraining the animal with a collar and sash until the moment to pounce. This image might have been inspired by a display at Windsor Great Park in 1764 when a cheetah was sent on to kill a royal stag but found itself at the end of its formidable antlers and immediately ran for safety.

The exhibition ends with a fascinating selection of drawings from the artist’s last great, but unfinished, endeavour, lengthily entitled, A Comparative Anatomical Exposition of the Structure of the Human Body with that of Tiger and a Common Fowl. In what amounted to 10 years’ work and 120 drawings Stubbs sought to identify similarities in the muscles and skeletons of different species such as a running hen, a standing monkey and a crouching human. His research was crucial to scientific studies at the time and was a precursor to On the Origin of the Species by Charles Darwin which was published 53 years after his death in July 1806.

Contemporaries judged him as a “master of the highest forms of art” and also a “painter of lowly animals”. Lowly! If anyone illuminated the nobility of the horse with such truth and authenticity it is the flayer of Horsktow, the painter who believed that nature “was and is superior to art”.