A poignant review of artist Khadija Saye who was among the victims of the Grenfell tragedy

The photographic prints of Khadija Saye have what can best be described as a kind of powerfully transgressive, tumultuous quiet. This is mixed with something spiritual, almost ritualistic.

The Crowned explores the nature and notion of black women’s identity through our hair. Saye’s portraits literally display the roots and the route of the almost ritualistic act of braiding and weaving.

The artist takes us up close and personal to what, on the surface, may seem casual. But on closer inspection, we are shown the work: the care; the precision, even the pain of braiding.

On another level, it is as if the entire raison-d’etre of the woman-subject is the state and the quality of her hair.

The title Crowned then has a double-meaning: hair as the crowning glory and also hair as a shield; a veil.

The women have turned their backs to us. Or are we behind them? Maybe they’re invisible to us. Saye makes no judgment. Again, she shows us what she herself sees.

The question hanging in the air is this: who is the subject doing all this for? Why is she doing it? Does she exist outside of her ‘crown’, Saye is asking us to contemplate. To stop. To wonder at what lies beneath the everyday.

In that she is like her mentor, the artist Nicola Green. Both take apart what they see, interrogate it; reinterpret.

Saye’s intricate and fragile women with braided hair stare ahead into something that does not reflect back to them.

Are they in a void? A closet? On the precipice of a ledge deep in the night, their pretty crowns the last act of a life…or the beginning of one?

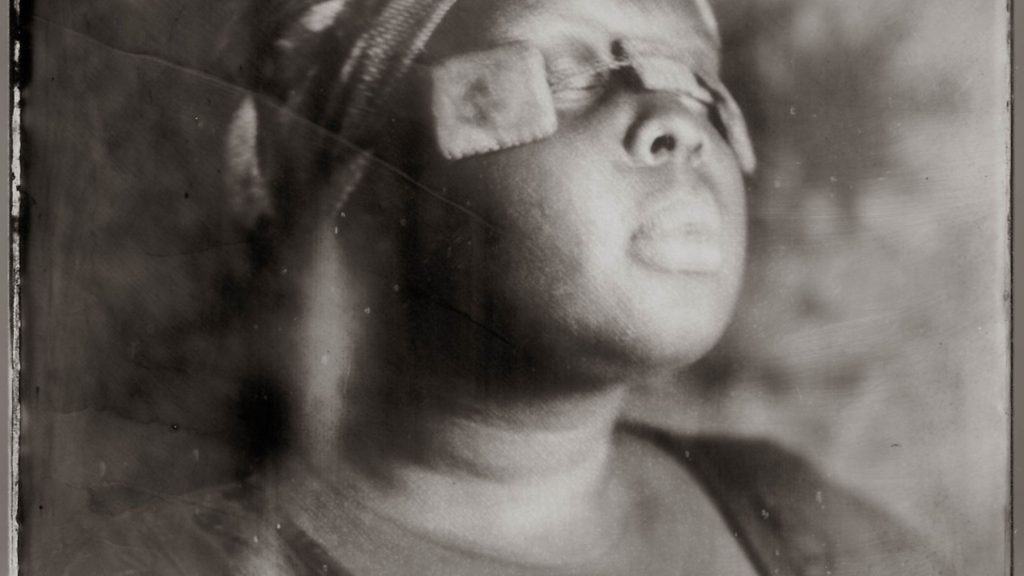

Dwelling: in this space we breathe described as ‘a series of wet plate collodion tintypes that explores the migration of traditional Gambian spiritual practices and the deep rooted urge to find solace within a higher power’ features the artist herself.

Currently on exhibit until November 26 at the Diaspora Pavilion during the 57th Venice Biennale, Saye’s new work joins that of Nicola Green, Sokari Douglas Camp, Isaac Julien, Yinka Shonibare MBE and other distinguished artists in the city known in the Adriatic as La Serenissima.

And on the surface, Saye’s self-portraits, made in collaboration with the artist Almudena Romero, a visual artist working with a wide range of photographic processes from early printing techniques such as cyanotype, salt printing and wet plate collodion, seem as serene as Venice itself. Yet Venice has its secrets, and Saye, in the quiet of these portraits, reveals hers.

Amulet is mask-like, hidden. But it is also masque-like: like the thing you hold up to your face at Carnival in Venice. This work comes at you out of the mist. Perhaps, too, out of her Gambian heritage. As usual, Saye aims to reveal, explore, dissect and rebuild.

Andichuri is the artist-as-listener. Maybe to an ancient tale. Maybe to some inner instructions. Maybe she is drifting off to sleep. She seems to have found something and is listening for it to give her its response.

The wet plate collodion technique gives these portraits an ancient feel, and at the same time they are right now. You half expect the artist to burst out laughing.

You want her to.

Sothiou is also included in the series.

Here Saye has her back to us. There is something in her hand: it could be her working tools; or reeds from some river; branches from a tree. In its own way Sothiou has the confidence of a Rembrandt or a Goya, not necessarily in technique but in insouciance. Like these Masters, Saye knows that the real point of it all is to find, everyday, the courage to face The Work. That Work consists of finding your own voice; then finding the way to use it .

Saye has found it.

A silkscreen print on paper of Sothiou is on display now at Tate Britain.

Beneath it is a sign:

IN MEMORY OF KHADIJA SAYE AND ALL WHO LOST THEIR LIVES AT GRENFELL TOWER ON 14 JUNE 2017

Sothiou is in the memorial space and remains there for around a fortnight, part of Tate Britain’s free collection displays.

All are welcome during the gallery’s public opening hours.

Khadija Saye was born in 1992.

Out of adversity, hard work, technique; support; and her own great artistry – she has arrived.

Go. See what Khadija Saye has created.