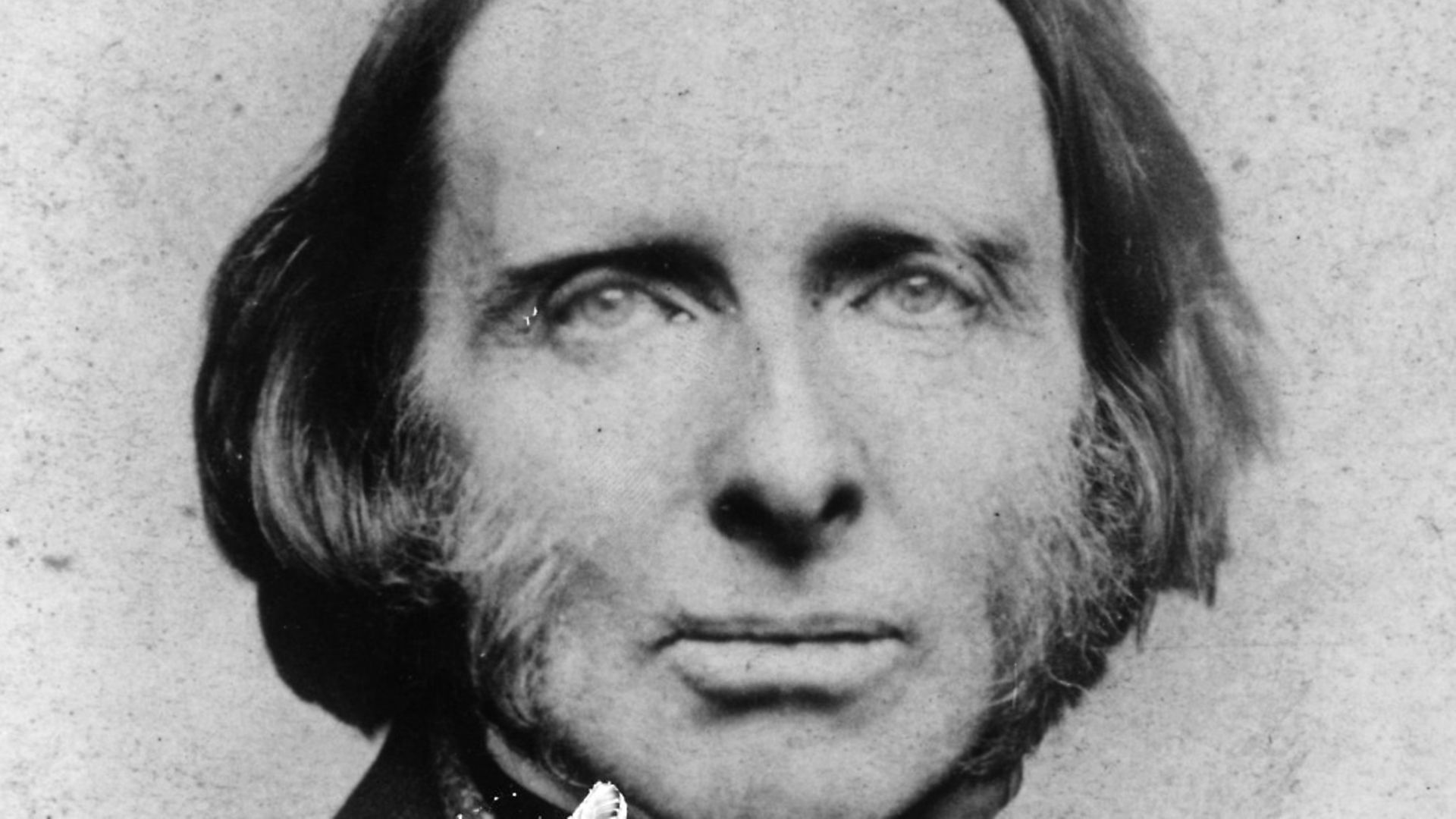

Often remembered as a curmudgeon who resisted modernity, a new exhibition shows John Ruskin was a visionary who still inspires forward-thinking.

The Victorian John Ruskin is among the most famous art critics and theorists of the modern era, though today he is remembered as much for his supposed horror of female pubic hair, as for his championing of JMW Turner (1775-1851) and the painters of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Critics universally condemned the Pre-Raphaelites, who were described in a particularly scathing review in the Times as suffering from ‘a strange disorder of the mind or eyes’, resulting in an ‘absolute contempt for perspective and the known laws of light and shade’, and Ruskin’s admiration of painters including John Everett Millais (1829-1896) and William Holman Hunt (1827-1910) put him at odds with the Victorian art establishment. Even so, the ease with which he could be moved to outrage earned him his name as a hopeless reactionary.

His opinions extended beyond art: he railed against modernity in its diverse manifestations. Cycling was, he said, an ‘invention for superseding human feet on God’s ground’. Rail travel was a means to ‘transmute a man from a traveller into a living parcel’, the Houses of Parliament were ‘the most effeminate and effectless heap of stones ever raised by man’.

But according to Ruskin: The Power of Seeing, an exhibition to mark the bicentenary of his birth, his reputation as an eccentric curmudgeon has obscured the broader and more positive aspects of his legacy. His ideas about art, education, the economy and the environment were essential to the emergence of the Arts and Crafts movement in the late 19th century, the foundation of the National Trust and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB), and are as relevant now as they were during his lifetime.

Though Ruskin expended countless words on the ills of modern life, Louise Pullen, curator of the new exhibition at London’s Two Temple Place, insists that he was a man of action.

‘He wanted to know why society was changing and what could be done about it’, she says. His response, accordingly, was to establish the Guild of St George. Founded in 1871, the society aimed to improve the lives of ordinary people through a return to traditional values, rejecting industrialism and mass production in favour of a renewed emphasis on the dignity of skilled labour.

The Guild promoted arts education, the revival of craftsmanship, and sustainable agricultural practices in what amounted to a new social model. Ruskin believed that Britain’s wealth and power had been accrued at the expense of both the environment and the working population: the Guild was his attempt to counter the negative effects of industrialisation by promoting a way of life that was essentially rural, that he believed could nourish individuals, both physically and intellectually.

At the heart of Ruskin’s philosophy was the belief in the edifying potential of beauty, and he maintained that worthwhile creative and artistic activity could not be undertaken by people ‘unless they are living contented lives, in pure air, out of the way of unsightly objects, and emancipated from unnecessary mechanical occupation’. In 1875 he established a small museum in one room of a cottage in Walkley, then a village outside Sheffield, but now absorbed into the city. The museum was intended to be the first of many, and was aimed at Sheffield’s steel workers, whose craftsmanship Ruskin particularly admired, though he lamented their living and working conditions.

Up a hill, above the smoke and dirt of the city, St George’s Museum entailed an excursion into countryside and fresh air as much as it provided an enriching and educational experience, and was open late and on Sundays so that workers might visit in their limited free time. An idiosyncratic collection of objects was collected there, a selection of which is displayed outside Sheffield for the first time in the Two Temple Place exhibition.

Representative of Ruskin’s tastes and interests, the collection includes natural objects, botanical and ornithological drawings, architectural casts and copies of Renaissance artworks, as well as prints after JMW Turner. The Victorian Gothic mansion at Temple Place, built for the American businessman William Waldorf Astor in 1895, provides an ideal setting and here, as at the cottage in Walkley, geological samples and precious stones sit next to illuminated manuscripts, and architectural drawings are side by side with studies of exotic birds and paintings of landscapes and buildings.

If Ruskin wanted to instil in the metal workers of Sheffield an appreciation of beauty, it was principally the beauty of nature that concerned him. The making and appreciation of art was, for him, a means by which a person’s sensibilities could be tutored the better to understand the splendour of God’s creation.

In the first volume of his best known work, Modern Painters (1843), Ruskin advised artists to ‘go to Nature in all singleness of heart, and walk with her laboriously and trustingly, having no other thoughts but how best to penetrate her meaning, and remember her instruction; rejecting nothing, selecting nothing, and scorning nothing; believing all things to be right and good, and rejoicing always in the truth’. It was advice followed by a generation of artists, notably the Pre-Raphaelites, who took to painting outside, from nature.

For Ruskin, the act of drawing out of doors, and looking at the work of great landscape painters such as Turner, fostered an understanding and respect for nature that was of value to everyone, not only artists. Ruskin’s own works are on display here in some number, and the minute world of carefully observed details seen in, for example, his Study of Moss, Fern and Wood-Sorrel, upon a Rocky River Bank (1875-79), suggest the soothing effects of nature, in which he was capable of becoming completely absorbed.

If nature provided Ruskin with an escape, he struggled with its earthier aspects, as suggested by the admittedly apocryphal explanation for the failure of his marriage to Effie Gray. The marriage was unconsummated, because, said Effie, ‘he had imagined women were quite different to what he saw I was, and that the reason he did not make me his wife was because he was disgusted with my person [that] first evening …’ This has been generally understood to mean that the artistic tradition of depicting women as entirely hairless had left Ruskin ill-prepared for the reality.

Ruskin’s dismay at the pollution of the landscape by industry was related most vividly in two lectures delivered to the London Institution, and published in 1884 as The Storm Clouds of the Nineteenth Century. Today, it is hard not to read it as prophetical, anticipating our current understanding of climate change.

Even so, his description wavers between the observational and the metaphorical, and having ascribed the black skies to furnace chimneys, he writes: ‘It looks more to me as if it were made of dead men’s souls – such of them as are not gone yet where they have to go, and may be flitting hither and thither, doubting, themselves, of the fittest place for them.’

For Louise Pullen, Ruskin’s lecture is as much about the state of society as it is about the environment. ‘He was concerned about the environment, and he was very aware of how the environment was changing, but The Storm Clouds of the Nineteenth Century was also born from his poor mental health, and his depression about where society was going. For him, pollution was as much about a polluted society as the environment.’

In drawing parallels between the destruction of the environment and the abject conditions endured by Britain’s poor, Ruskin found a visual lexicon that conveyed his distress at the state of a society that had sacrificed its most precious resources for the sake of profit. For him, Britain’s success as a commercial power was of no consequence while its people suffered, and in 1860 he wrote: ‘That country is the richest which nourishes the greatest numbers of noble and happy human beings.’

Though Ruskin was not alone in his concerns, his approach was unusually holistic and the exhibition encapsulates his ideas in a jarringly modern word: wellbeing. For Pullen, the exhibition offers visitors a chance to be enriched by what they see in exactly the way Ruskin intended a century and a half ago. ‘I hope it opens people’s eyes up to the glimpses of beauty he was trying to show, through drawings of botany or birds or landscape. He was just trying to drop little aspects of loveliness into people’s lives and I really hope people will see that, and look around them a bit more, and perhaps consider their own wellbeing through what he was trying to do.’

Even within his own lifetime, St George’s Museum outgrew its single room in Walkley as the collection expanded and Ruskin’s ideas gained influence. Though it is impossible to measure the impact that the museum had on its visitors, records show that in some cases it must have proved a seminal influence.

The sculptor Benjamin Creswick visited the museum as an adolescent, before going on to be trained by Ruskin himself, while the 14-year-old Omar Ramsden would later become a leading silversmith.

Today, the collection once housed by St George’s Museum in Walkley is administered by Museums Sheffield, while the Guild of St George, now almost 150 years old, continues to promote Ruskin’s ideas, which have been formative not just in thinking about the arts and the environment, but in urban planning and social policy. Most recently, health secretary Matt Hancock’s initiative enabling doctors to prescribe cultural activities instead of anti-depressants, serves as evidence of the continuing relevance of Ruskinian thinking.

John Ruskin: The Power of Seeing is on at Two Temple Place, London, until April 22