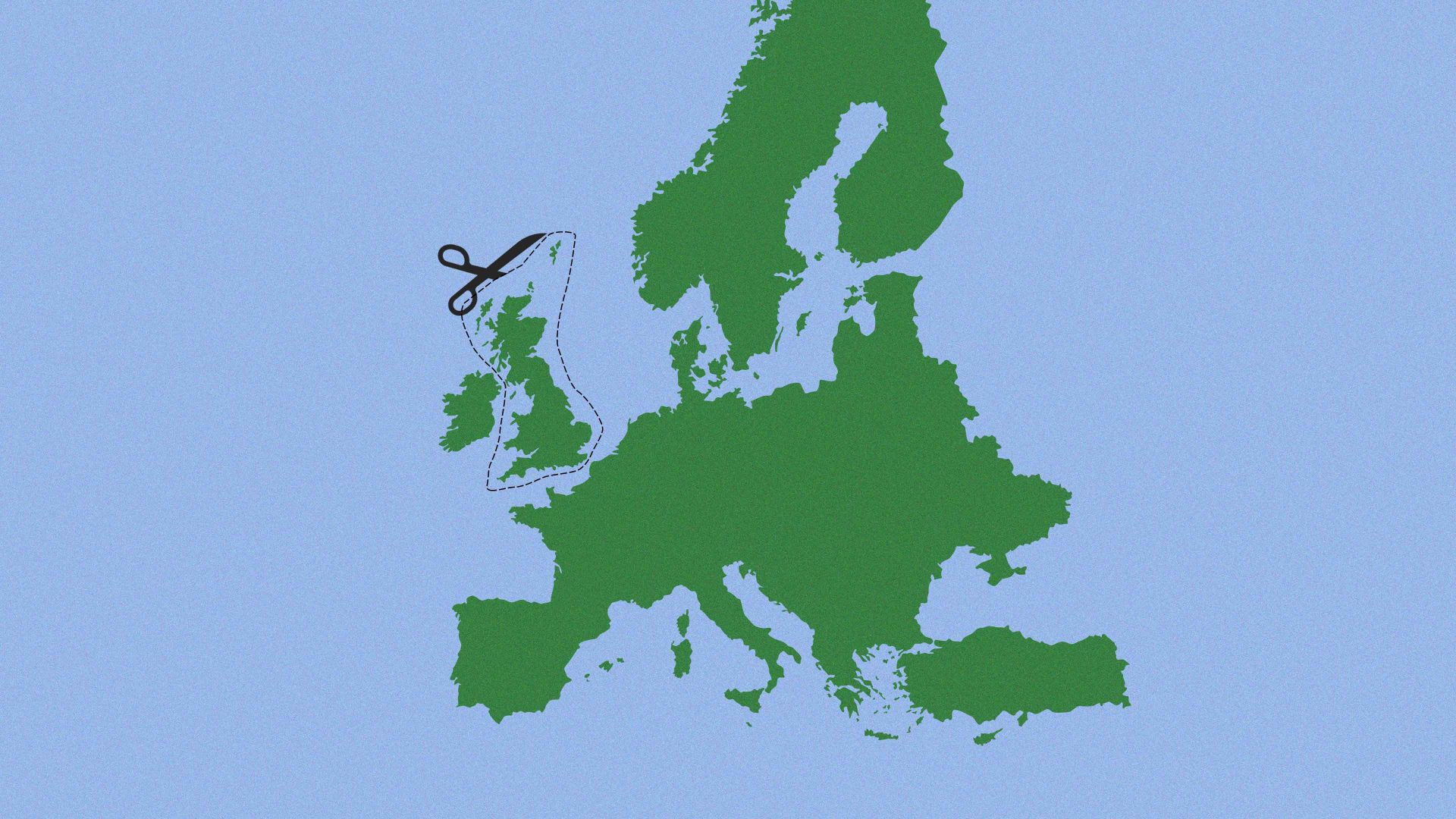

After touring the European Parliament’s museum in Brussels, I lingered in the gift shop and saw the tea towels, decorated with a map of the European Union. There was something odd about it. You know that bit of the North Sea just north of France and east of Ireland? The last time I looked at a map, the United Kingdom sat there. On this map, there’s only sea.

I was staying in Brussels with my son, Peter, and his Spanish wife, Raquel. Most of Peter’s British contemporaries went home soon after Brexit, as opportunities in Brussels diminished. Brits in Brussels tend to be a generation older than him (he’s in his late 30s), and almost none are younger.

“I think I’ve dealt with one British colleague since Brexit,” a Hungarian EU staffer tells me, and the only Brits Peter knows were there before Brexit.

His friendship group is very international. Among the first 10 people I met at a Halloween party, given by a Belgian and her Hungarian fiancee, I counted nine different nationalities. The predominant language was English, but I heard snatches of French, Spanish, and Dutch. Peter and I were the only Brits, and he is the only Brit at most social gatherings.

Raquel and many of their friends work for the European Commission, a career path blocked for Peter unless he acquires citizenship of an EU country. But Peter put down roots in the city before Brexit, learned French and Spanish, and acquired affection for, and understanding of, the European institutions.

Are we missed? A bit. One Maltese employee at the commission remembers with nostalgia the press review when the journalists mocked the spokespeople – “a very British thing”.

But mostly they don’t think about us much, and when they do, there’s a sense of bafflement.

“We in Lithuania so looked forward to joining, so happy to be allowed to join, yet you threw it away,” said one commission staffer. “We are Europeans – that’s made clear in Lithuanian schools – but many of us love the UK. I had friends at home who cried when they heard about the Brexit vote.”

Her Spanish colleague chimed in: “For us, free movement was important, because we didn’t have it in the 1950s and 60s. It was seen as a huge opportunity.” She still struggles to understand why Britain has grown to hate it. “There’s a sense of failure, of betrayal.”

“You’ve left us alone with these lunatics,” said a Swede, only half joking, for Sweden used to rely on British support to resist further integration.

But at least, surely, English remains the language in which the European institutions work?

Well, in a sense. The language in which the commission does its business, in which meetings are held and all official documents are written, looks every year less and less like the language you and I speak.

The British staffers used to protect it, to point out gently that this or that construction might sound fine in French or Spanish but it wouldn’t do in the language of Shakespeare. But they are no longer there, and of the two remaining Anglophone nations, Ireland has chosen to nominate Gaelic as its official language, and Malta has nominated Maltese.

So a new language is developing, which may eventually be related to English only in the way that Yiddish is related to German, or Niçois to Italian. It is developing just as a new language always develops, by using English words in French, Spanish or Italian constructions, and by importing words from European languages. I’d be tempted to call it Eurish.

In Eurish, you do not attend a meeting; you assist a meeting, because the French word assister means attend. You don’t plan a project, you have a planification. A deposit is a caution (because it is in French.) Spanish has contributed “a planning” for a schedule, “formation” for education, and “actually” for currently.

More are added each year.

Replacing English as the commission’s working language would be difficult. But the French are taking the commission to court over certain examinations for commission posts being in English only; and increasingly it’s Eurish anyway.

The waters of the North Sea really are closing over the British. I should have bought that tea towel while I had the chance.